Clarinet Concerto. Oboe Concerto. Flute and Harp Concerto

Wolfgang Meyer cl Hans-Peter Westermann ob Robert Wolf fl Naoko Yoshino hp Concentus Musicus Wien / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

(Teldec/Warner Classics)

There are happy and shapely performances of all three concertos here, but the particular delight is that of the latest and greatest of them, the Clarinet Concerto, which Wolfgang Meyer plays on a basset clarinet – that is, an instrument with an extension allowing it to add four semitones at the bottom of its compass. This is the instrument for which the work was originally composed, although only a text adapted to the normal clarinet has come down to us. The reconstruction used here, slightly different in some of its detail from others I have heard, works very well, making the familiar text’s rough places plain and logical; and it serves ideally for Meyer, with his rich and oily bottom register.

The first-movement tempo is on the leisurely side, giving him plenty of opportunity for refined and subtle moulding of the lines. Even the bravura music, shaded with delicacy, emerges with expressive content, and I admired especially Meyer’s light, fluid articulation of semiquaver runs. There is a rapt account of the Adagio and a lively Rondo, beautifully articulated; in both, the availability of the extra notes makes clear the logic of Mozart’s lines as he must have conceived them. Meyer has less rounded, more reedy a tone than many players favour. He adds a little ornamentation here and there, where Mozart seems to invite it; just once or twice I wasn’t quite comfortable with what he did. Altogether, though, a very musical and appealing performance.

In the Flute and Harp Concerto there is some delicate, clear playing from both soloists in what is perhaps a slightly austere reading of the first movement. The Andantino, too, is taken rather slowly, and with a chamber-musical refinement, with coolly aristocratic flute playing from Robert Wolf and gently expressive shaping from Naoko Yoshino. I thought the finale was a little restrained and pensive, certainly graceful but not quite as dance-like or as much fun as this gavotte-rhythm piece ought to be (and the interpretation of the appoggiatura in the main theme seems to me perverse). Hans-Peter Westermann contributes a sweet-toned and neatly phrased account of the Oboe Concerto, yet again rather leisured in tempo, in the finale in particular, and with one or two orchestral oddities especially in matters of accentuation (characteristic of Harnoncourt’s direction). But altogether a disc with much polished and sensitive playing. Stanley Sadie (March 2001)

☆

Horn Concertos

Dennis Brain hn Philharmonia Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

(Warner Classics)

Dennis Brain was the finest Mozartian soloist of his generation. Again and again Karajan matches the graceful line of his solo phrasing (the Romance of No 3 is just one ravishing example), while in the Allegros the crisply articulated, often witty comments from the Philharmonia violins are a joy. The glorious tone and the richly lyrical phrasing of every note from Brain himself is life-enhancing in its radiant warmth. The Rondos aren't just spirited, buoyant, infectious and smiling, although they're all these things, but they have the kind of natural flow that Beecham gave to Mozart.

There's also much dynamic subtlety – Brain doesn't just repeat the main theme the same as the first time, but alters its level and colour. His legacy to future generations of horn players has been to show them that the horn – a notoriously difficult instrument – can be tamed absolutely and that it can yield a lyrical line and a range of colour to match any other solo instrument. He was tragically killed, in his prime, in a car accident while travelling home overnight from the Edinburgh Festival. He left us this supreme Mozartian testament which may be approached by others but rarely, if ever, equalled, for his was uniquely inspirational music-making, with an innocent-like quality to make it the more endearing. It's a pity to be unable to be equally enthusiastic about the recorded sound. The remastering leaves the horn timbre, with full Kingsway Hall resonance, unimpaired, but has dried out the strings. This, though, remains a classic recording.

☆

Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra No 10. Flute and Harp Concerto. Horn Concerto No 3

Ulrich Hübner hn Frank Theuns fl Marjan de Haern hp Yoko Kaneko pf Anima Eterna / Jos van Immerseel pf

(Zig-Zag)

Director and fortepianist Jos van Immerseel is a veritable pioneer of period Mozart. Belgian period-instrument orchestra Anima Eterna’s exuberant performances reveal a natural union of pioneering spirit and refreshing musical flavours. The performers show commendable integrity in their approach to using historical instruments: the characteristics and origins of the solo instruments are each enthusiastically described in the booklet-note but the loving care given to detail in this joyful music means this is never in danger of seeming merely a dour academic exercise.

The invigorating Concerto for two pianos (Salzburg, 1779-80) opens proceedings with a revitalising fix of blazing horns, vibrant woodwind and articulate strings. Anima Eterna’s stunning playing in the tuttis is perfectly balanced with the fluent playing of Immerseel and Yoko Kaneko. After such joie de vivre, the Flute and Harp Concerto (Paris, 1778) features sensitively judged playing from Frank Theuns and Marjan de Haer. I have rarely encountered such an affectionate and warmly stylish performance of the Allegro, and the Andantino is ravishing.

Ulrich Hübner plays with attractive immediacy in the Third Horn Concerto, composed around 1787: the poetic Romance has a lyrical elegance one seldom hears from even the best natural horn players, and an infectiously sunny performance of the dance-like Allegro concludes this magnificent recording with a charismatic flourish. These performances are radiant: if you buy only one Mozart CD this anniversary year, let it be this one. David Vickers (August 2006)

☆

Complete Piano Concertos

English Chamber Orchestra / Murray Perahia pf

(Sony Classical)

Mozart concertos from the keyboard are unbeatable. There's a rightness, an effortlessness, about doing them this way that makes for heightened enjoyment. So many of them seem to gain in vividness when the interplay of pianist and orchestra is realised by musicians listening to each other in the manner of chamber music. Provided the musicians are of the finest quality, of course. We now just take for granted that the members of the English Chamber Orchestra will match the sensibility of the soloist. They are on top form here, as is Perahia, and the finesse of detail is breathtaking.

Just occasionally Perahia communicates an 'applied' quality – a refinement which makes some of his statements sound a little too good to be true. But the line of his playing, appropriately vocal in style, is exquisitely moulded; and the only reservations one can have are that a hushed, 'withdrawn' tone of voice, which he's little too ready to use, can bring an air of selfconsciousness to phrases where ordinary, radiant daylight would have been more illuminating; and that here and there a more robust treatment of brilliant passages would have been in place. However, the set is entirely successful on its own terms – whether or not you want to make comparisons with other favourite recordings.

Indeed, we now know that records of Mozart piano concertos don't come any better played than here.

☆

Piano Concerto No 22

Alfred Brendel pf Academy of St Martin in the Fields / Neville Marriner

(Philips)

Brendel's first recording of Mozart's expansive and luxuriantly scored Piano Concerto in E flat , K482 appeared 14 years ago (8/69), and it is fascinating to compare it with this new one. Both are notable for their sense of style and their clean but always sensitive and musical articulation in runs, and both show a readiness to embellish Mozart's oflen sketchy melodic line: indeed, Brendel's elaboration of the solo part in the lovely Andantino cantabile episode in the final Rondo might almost be considered overdone, tasteful though it is. But the new performance has, as one would expect, a maturity and authority not to be found in the earlier one; the cadenzas (by Brendel himself - Mozart's own were probably never written down, and have certainly not survived) are appropriate and reasonably succinct; and Brendel is less eager to join in the orchestral tutti, a practice which, though historically justifiable, makes musical nonsense when the solo instrument is a modern grand. In addition, the new recording, technically first-rate, has the benefit of exemplary accompaniment by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields under the unerring guidance of Neville Marriner. For anyone wanting a recording of K482 as near perfection as one is likely to get, this new issue is the obvious answer. Robin Golding (October 1977)

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 18-22

Northern Sinfonia / Imogen Cooper pf

(Avie)

Imogen Cooper’s two previous Mozart concerto releases with the Northern Sinfonia and Bradley Creswick (12/06 and 8/08) have both been roundly praised and no one who enjoyed them is likely to be disappointed by this latest instalment. Indeed, the qualities that make Cooper quite simply one of the finest pianists this country has produced make her perfect for Mozart duty. Clear but velvety ringing tone, perfect voicing of chords, unsleeping alertness to the necessary subtleties of rubato and line, and above all an ability to realise this music’s intimate poetry that can make you catch your breath, make these performances the kind that any musician should listen to and learn from.

There are good opportunities to display such artistry in these two concertos, both of which have minor-key slow movements of considerable emotional sophistication, to which Cooper responds with depth and grace. She is not always quite matched in this by the orchestra, it must be said – the wind episodes in the Andante of K482 are rather cold and the rapt beauties of Cooper’s playing of the minuet theme in the same work’s finale are slightly trodden on by the unison violin line that goes with it – but in general the Northern Sinfonia provide backing that is musically engaged, texturally transparent and technically right up to the mark. Their opening to K482 has all the rich grandeur it needs, and here indeed is one quality which some listeners may feel is a little lacking in Cooper. Likewise playfulness and simple hard-edged brilliance of tone, for instance in Paul Badura-Skoda’s witty cadenzas for K482 or the lead-backs in the finale of K456. But then, when what she does give us is so much, why worry too much about what she doesn’t? Lindsay Kemp (January 2011)

☆

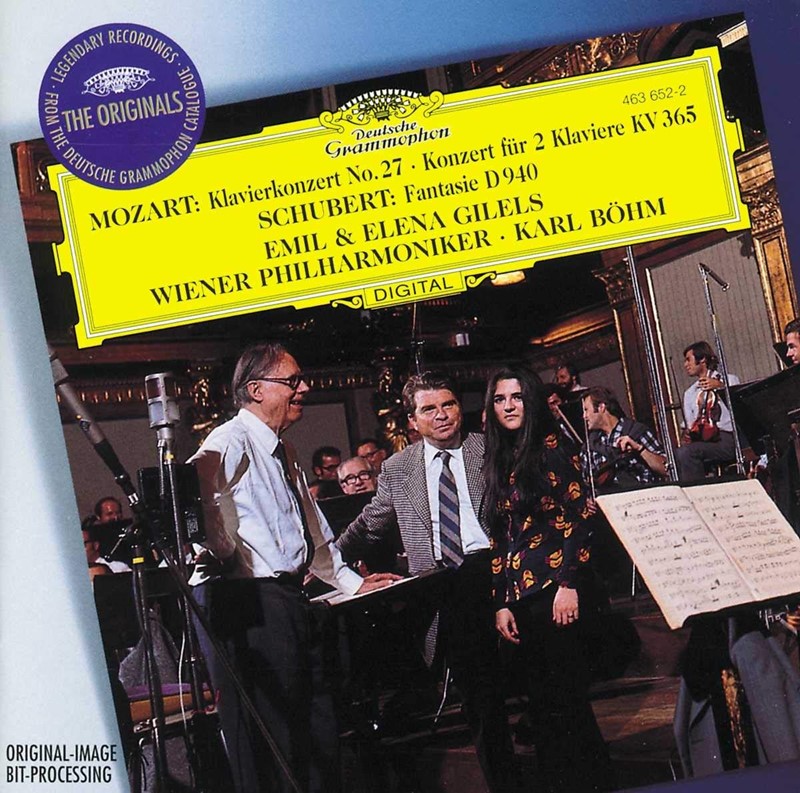

Piano Concerto No 27. Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, K365

Emil Gilels, Elena Gilels pfs Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Karl Böhm

(DG)

This is the most beautiful of Mozart playing, his last piano concerto given here by Emil Gilels with total clarity. This is a classic performance, memorably accompanied by the VPO and Böhm. Suffice it to say that Gilels sees everything and exaggerates nothing, that the performance has an Olympian authority and serenity, and that the Larghetto is one of the glories of the gramophone. He's joined by his daughter Elena in the Double Piano Concerto in E flat, and their physical relationship is mirrored in the quality, and the mutual understanding of the playing: both works receive marvellous interpretations.

We think Emil plays first, Elena second, but could be quite wrong. The VPO under Karl Böhm is at its best; and so is the quality of recording, with a good stereo separation of the two solo parts, highly desirable in this work. Stephen Plaistow (November 1974)

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 18 & 22

Ronald Brautigam fp Cologne Academy / Michael Alexander Willens

(BIS)

In a letter to his daughter Nannerl, Leopold Mozart expressed his pleasure at the interplay of the various instruments after hearing Wolfgang perform the B flat Concerto, K456. I experienced comparable delight listening to this beautifully recorded performance from Ronald Brautigam and the responsive Cologne period band. In a Mozartian opera reimagined in instrumental terms, fortepiano, wind and strings conspire and banter with captivating grace and legerdemain.

Likewise using a modern copy of an Anton Walter fortepiano, Brautigam favours rather fleeter tempi, and a more direct style of phrasing, than Robert Levin on his fine L’Oiseau Lyre recording with Christopher Hogwood (11/96 – nla). In the first movement, with its suggestion of a march for toy soldiers, Levin is more reflective, Brautigam more playfully extrovert, stressing continuity of line above rhythmic and tonal nuance. I prefer Brautigam’s more flowing manner in the G minor Andante, where Levin’s minute inflections can sound over-exquisite. The period woodwind, led by the virginal solo flute, are especially delectable in the serenading G major variation. As to the ‘hunting’ finale, you’d go far to hear a performance of such darting wit and panache, or one that exudes such a sense of delighted collusion between woodwind – each one an operatic character in itself – and the fortepiano’s sweet, silvery treble.

In the more opulently scored K482 (trumpets and drums, oboes replaced by clarinets) I ideally wanted a fuller string tone than the 14 Cologne players can muster. That said, the performance is scarcely less enjoyable than that of K456, not least in the C minor Andante, which at Brautigam’s unusually mobile tempo is just as touching, and (in the confrontational second variation) more dramatic, than in more gravely paced readings. Brautigam generates an exhilarating forward sweep in the regal opening movement – Levin (9/98 – nla) is more inclined to linger over detail – and an infectious sense of fun in the finale, where swiftness never compromises immaculate clarity of articulation. His own cadenzas are short and to the point. Levin’s are longer, cleverer and more consciously showy. Again, some may find Brautigam too swift in the finale’s sensuous Così fan tutte-ish interlude, with its ravishing clarinet sonorities. For me the easily flowing pace and delicate touches of embellishment, predictably less lavish than Levin’s, mesh perfectly with the animated naturalness of the whole performance. Richard Wigmore (July 2014)

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 20 & 25

Martha Argerich pf Orchestra Mozart / Claudio Abbado

(DG)

A disc of Mozart piano concertos recorded in concert by Martha Argerich with Claudio Abbado and Orchestra Mozart was always going to be a delicious prospect. Hearing of Abbado’s death as I write these words turns the pleasure of hearing it into something altogether more bittersweet. Lucky were those souls who heard these performances of the D minor Concerto, K466, and the C major Concerto, K503, at the Lucerne Festival last March – an experience denied London audiences a few months later when first the ailing Abbado and then Argerich cancelled their appearances. (Not that the stand-ins were any sort of disappointment – Bernard Haitink and Maria João Pires.)

Both Argerich and Abbado have returned to Mozart late in their careers: she revisiting the piano duets and a handful of concertos; he forming the hand-picked and youthful Orchestra Mozart specifically for the purpose. Not uncharacteristically for her, the present concertos are both works she has recorded before – the D minor in 1998 (Teldec/Elatus, 6/99), the C major in 1978 (EMI, 4/00) and again as recently as 2012, during that year’s Progetto Martha Argerich at Lugano (EMI, 8/13). Of that last recording, Caroline Gill wrote that it was ‘musically and technically equal to anything she has recorded in the studio’; but here again she surpasses herself. The backing of the exquisitely refined Orchestra Mozart grants full rein to her personal brand of expressivity. Every note matters, both individually and as part of a phrase, and once again her microscopic alterations of touch make even the most mundane run of semiquavers dance and sing, imparting something undefinable and treasurable to her performances here.

The C major comes first on the disc, the grandeur of Abbado’s introduction contrasting with the spirited filigree of Argerich’s solo contribution. She is fully alive to the darker undertow of the D minor, perhaps the only disappointment being Abbado’s refusal fully to acknowledge the way the work’s Sturm und Drang demeanour is undercut by the whiff of Singspiel at the work’s close, the sound world of Don Giovanni giving way to that of Papageno and The Magic Flute. Argerich sets off with a will in the finale but doesn’t let herself get carried away in the Romanze’s central convulsion, sticking firmly to the tempo of the gentler outer sections. Where she does let go the full power of her virtuosity is in the cadenzas: her teacher Friedrich Gulda’s in K503, the familiar Beethoven in K466. Familiar, perhaps, but rendered almost hallucinogenic when refracted through the prism of her unique musical imagination. David Threasher (March 2014)

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 25 & 27

Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Piotr Anderszewski pf

(Warner Classics)

I wonder if Piotr Anderszewski has it in mind to record all of Mozart’s major piano concertos. This is his third such coupling; the first appeared in 2002 (Nos 21 and 24 – 4/02), so at this rate he’ll be about 80 by the time he finishes. His recordings keep on getting better and better, too – having anyway started out at a remarkable standard – so Mozartians may well be in for decades of treats to come, however piecemeal we are fed them.

Anderszewski habitually pairs a lyrical work with a more dramatic one: the ubiquitous C major, once indelibly associated with a Swedish film, versus the clarinet-imbued Sturm und Drang C minor, followed four years later by the serene G major, No 17, set against the agitated D minor, No 20 (5/06). Here it is the very last concerto – often described as ‘autumnal’ or ‘valedictory’, given its proximity to Mozart’s death (although it may have been started up to three years earlier) – prefaced by the triumphant C major work whose chief motif seems almost to quote the Marseillaise. These have often been thought to signal a departure from the quasi-operatic-ensemble construction of the run of concertos from the mid-1780s, moving towards a more discursive unfolding in K503 and a more simply songlike one in K595. Nevertheless, the wonderful playing of the Chamber Orchestra of Europe shows just how fully the earlier work, especially, is dominated by woodwind conversation and that it can’t be too distantly related to the sound world of Figaro’s ‘Non più andrai’.

Read the full Gramophone review

☆

Violin Concertos

Giuliano Carmignola vn Mozart Orchestra / Claudio Abbado

(Archiv)

Virtuoso “violinism” and energising direction notwithstanding, neither Giuliano Carmignola nor Claudio Abbado seems inspired by the B flat Concerto, K207. Nor does slick dispatch do much for the first movement of the D major, K211; but this is not the shape of things to come. Carmignola steps away from neutrality in the succeeding Andante. The music breathes a life of its own as he ardently inflects its phrases to shape the tension and relaxation of his line which – as elsewhere – he also embellishes. And pauses are decorated with lead-ins. Here is personal involvement that from now on is present in full flower.

It’s a flowering for Abbado too, as he summons a passionate advocacy that takes in the implications of key and time signatures on atmosphere and pacing, uses dynamic markings and intuitive accents to keep rhythm aloft, adjusts the timbres of the wind instruments (oboes are vivid or subdued, horns play in alto or basso) to suit the colouration he requires, and aerates the orchestral fabric for maximum clarity. Conducting and interpretation are in the realms of greatness – and no mistake.

In the solo concertos, Carmignola is recorded with varying but small changes of volume. His positioning is steadier in the Sinfonia concertante; and so is his placement with the artistic, if slightly reticent, Danusha Waskiewicz. Nevertheless, their skilled dovetailing and intelligent use of tone colour speak of symbiosis. Abbado remains primus inter pares, watchful, supportive and fortifying. Pity the sound isn’t always clear and detailed. Superlative music making deserves consistently superlative recording. Nalen Anthoni (September 2008)

☆

Violin Concertos Nos 3-5

Arabella Steinbacher vn Festival Strings Lucerne / Daniel Dodds

(Pentatone)

In the booklet accompanying this issue, Arabella Steinbacher writes: ‘These concertos have been with me since early childhood…I feel they are very close to my heart.’ Anybody tempted to dismiss this as a marketing ploy will soon change their minds on listening to these performances – they really do give the impression of a project backed by an unusual degree of sympathetic understanding.

Steinbacher has a way of searching out what gives each passage, each phrase, its individuality, getting it to speak to us through slight changes in dynamic or emphasis. Nothing is forced: the quick movements are fast enough for the passagework to sound brilliant but always with space for elegant shaping. The Lucerne Festival Strings are a small enough body to allow even accompanying lines to be played in a positive, lively manner (notice the variants in the support the violins give to the returns of the rondo theme in K216’s finale). A top-class recording enhances the sensation of keen participation. Steinbacher finds her sweetest tone for the slow movements; elsewhere, there’s a strong awareness of the sense of fun that pervades many parts of these youthful masterpieces. And she finds an extra injection of fire for the Turkish episode in K219’s finale.

The purist in me noticed occasional over-smooth articulation and, at the other extreme, very short spiccato bow strokes (in the finale of K218, for example). But these are minor issues, within these highly individual, deeply satisfying accounts. Duncan Druce (August 2014)

☆

Divertimenti

Scottish Chamber Orchestra Wind Soloists

(Linn Records)

Mozart informed his father that he had composed the Serenade K375 ‘rather carefully’ to impress Herr von Strack, a Viennese nobleman sporting the splendid title of ‘Gentleman of the Emperor’s Bed Chamber’. Whether in its original Sextet incarnation, performed here, or its later Octet version, this is music that both celebrates and, as Mozart surely knew, far transcends the tradition of al fresco Harmoniemusik. If you know the more familiar Octet version, you might regret the loss of the oboes’ pungent dissonances near the opening, or of the oboe-clarinet dialogues in the Adagio. But the SCO soloists quickly allay any sense of deprivation. Like all the best ensembles in this music, they strike a nice balance between chamber-musical refinement and rustic earthiness. Natural horns lend a welcome abrasiveness to the tuttis; and the instrument’s variegated colours give added piquancy to the horn tune that sails in out of the blue near the end of the first movement. Clarinets can be dulcet, as in the tenderly phrased Adagio, yet are not afraid to rasp and bite, to specially vivid effect in the sprightly second Minuet. Tempi are aptly chosen (the opening Allegro properly maestoso), and accompanying figuration lives and breathes, not least in the Adagio, where the horns inject delightful touches of jauntiness into the poetic reverie.

The four Salzburg divertimentos for wind sextet of 1776 77 are far slighter. Yet each reveals the craftsmanship Mozart lavished even on trifles for Archbishop Colloredo’s dinner entertainment. The excellent booklet-notes fail to disclose why the Scottish players opt to perform the divertimentos with clarinets rather than the prescribed oboes. Still, while I missed the oboes’ pastoral plaintiveness in movements such as the opening siciliano of K252, the sensuous warmth of the clarinets is fair compensation in the mellifluous A flat major Trio, or the Adagio of K253. Again the players balance polish, poetry and sheer bucolic enjoyment. The rare example of a Mozartian polonaise in K252 goes with a jaunty swagger (other performances I’ve heard are rather more decorous), while the lusty contredanse finales exude an impish glee. I fancy Mozart would have smiled in approval. Richard Wigmore (February 2015)

☆

Serenades

Netherlands Chamber Orchestra / Nikolitch

(Pentatone)

The Haffner, a wedding serenade for the marriage of Elizabeth Haffner in July 1776, was an outdoor summer piece, which was not good for the band, whose members were expected to move around. Thus there are no timpani; and certainly no cellos, because there were aristocratic guests (the bride’s father had been burgomaster of Salzburg), so lowly musicians couldn’t sit while they stood. When Mozart later shortened this eight-movement work to a five-movement “symphony”, he enhanced the orchestration with cellos and drums.

Gordan Nikolitch goes further. He incorporates these instruments into the original format (as did Nikolaus Harnoncourt on a scrawny-sounding early CD), thus turning the Serenade into a fuller work. Harnoncourt also added timpani to the K249 March. Nikolitch doesn’t. This work has a stately expansiveness that only switches to a militaristic snap in the first movement of the Serenade, percussion now lending point both to a regal Allegro maestoso and, leading from it, a fiery alla breve Allegro molto. In the following Andante, the first of three “violin concerto” movements, Nikolitch shows that he is as superlative a violin soloist as he is a conductor, as unerring in his understanding of lyrical eloquence as he is of dramatic timing. He never puts a foot wrong. Neither does Pentatone’s production, which keeps the perspectives steady (for example, the violin is properly balanced with the ensemble and not pulled forward for the cadenzas). The range, transparency and tonal veracity of the recording offer a total vindication of SACD. This is a tremendous disc. Nalen Anthoni (January 2009)

☆

Symphonies Nos 18-24, 26, 27, 50 & K135

Academy of Ancient Music / Christopher Hogwood

(Decca)

This is surely one of the most important of the year's record releases. It should, and does, represent a milestone in the whole business of 'authentic instrument' recordings: for here we have a substantial body of music, much of it at the heart of the standard repertory, being recorded by one of the major British companies and by the leading London body specializing in music of the period. The enterprise acquires a certain internationalism from the use of Jaap Schroder, the Dutch violinist, to lead the orchestra (and in fact to direct it jointly with the harpsichordist, Christopher Hogwood), and from the use of Neal Zaslaw, a professor of music at Cornell University, as musicological consultant, to advise on such matters as editions and texts, the proper forces to use for the most authentic realization of each symphony, and the physical disposition of those forces (over which contemporary practices were followed: it may not have much direct effect on the sound one hears, except in such obvious matters as having first and second violins on opposite sides, but it certainly affects the way the performers interrelate while playing). On the evidence of this first release, I am inclined to greet the venture with enthusiasm and delight.

It will not be to everyone's taste. To put it over-simply: the traditional way of playing Mozart, on a modern symphony orchestra, and indeed even on a modern chamber orchestra, has been to emphasize two things: the line of the music (usually of course the first violin part), and the texture as a totality. Here the effect, and presumably to some degree the intention, is that the music is presented more in terms of a series of lines, or as a texture that needs less to be blended or homogenized than to be evaluated afresh in its internal balance at any and every moment. It makes the music more complex and more interesting, certainly more challenging, to listen to. The listener may find that the familiar broad sweep of some of these movements is lacking, but he will generally find the compensations more than sufficient. Better still if he can avoid thinking of it that way, and try, rather, to envisage this as the kind of sound that Mozart (as far as anyone can tell) had in mind, and to recognize that the music was written in the way it was because this is what Mozart expected. Stanley Sadie (December 1979)

☆

Symphonies Nos 25 & 29

English Chamber Orchestra / Benjamin Britten

(Decca)

Britten secures marvellous performances of these two symphonies by the 18-year-old Mozart. In the 'little' G minor he hrings out by the choice of moderate tempi and legato phrasing (listen to how lovingly he shapes the second subject of the finale, for example), the uneasy tension implicit in the two outer movements, without making the music sound aggressive or nervous. The Andante, warmly coloured by the two bassoons, moves at a gentle walking pace, yet never drags; the Minuet is strong and purposeful, with most distinguished wind playing in the Trio. The A major Symphony is no less well done, with muscular yet affectionate playing in the first and last movements, a glowing Andante, and a springy Minuet, with beautifully crisp dotted rhythms: I do not remember having enjoyed listening to it so much for a very long time.

The mellowness and sensitivity of Britten's performances are matched by the warmth of the Decca recording, which ably reproduces the Snape sound. Neville Marriner's highly accomplished, brisker, and - to be frank - less penetrating performances of the same two symphonies are matched by a brighter but shallower recording from Argo: in a word, the two interpretations and recordings are absolutely different. To my mind, the Britten disc is a revelation. Robin Golding (June 1978)

☆

Symphonies Nos 38-41

Scottish Chamber Orchestra / Sir Charles Mackerras

(Linn Records)

There is no need to argue the credentials of Sir Charles Mackerras as a Mozart interpreter, so let us just say that this double CD of the composer’s last four symphonies contains no surprises – it is every bit as good as you would expect. Like many modern-instrument performances these days it shows the period-orchestra influence in its lean sound, agile dynamic contrasts, sparing string vibrato, rasping brass, sharp-edged timpani and prominent woodwind, though given Mackerras’s long revisionist track-record it seems an insult to suggest that he would not have arrived at such a sound of his own accord. And in any case his handling of it – joyously supported by the playing of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra – is supremely skilled; rarely will you hear such well judged orchestral balance, such effective marrying of textural transparency and substance. The Jupiter in particular has a wonderful bright grandeur, yet reveals details in the brilliant contrapuntal kaleidoscope of the finale that too often go unheard.

Seldom, either, will you hear such expertly chosen tempi; generally these performances are on the quick side, but rather than seeming hard-driven they exude forward momentum effortlessly worn. Nowhere is this better shown in the slow movements (even with all their repeats they never flag, yet their shifting expressive moods are still tenderly drawn), but also conspicuously successful are the slow introductions to Symphonies Nos 38 and 39 (the former ominous but alert, the latter full of intelligent anticipation with shivery violin lines falling like cold rain down the back of the neck) and the Minuet movements of Nos 40 and 39 (whose cheeky one-in-a-bar lilt does wonders for its tootly clarinet Trio).

These are not Mozart performances for the romantics out there, but neither are they in the least lacking in humanity. No, this is thoroughly modern-day Mozart, full of wisdom and leaving the listener in no doubt of the music’s ineffable greatness. Lindsay Kemp (February 2008)

☆

String Quintets

Arthur Grumiaux, Arpad Gérecz vns Georges Janzer, Max Lesueur vas Eva Czako vc

(Philips)

Of the six works Mozart wrote for string quintet, that in B flat major, K174, is an early composition, written at the age of 17. It’s a well-made, enjoyable work, but not a great deal more than that. The C minor work, K406, is an arrangement by Mozart of his Serenade for six wind instruments, K398. It’s difficult not to feel that the original is more effective, since the music seems to sit a little uncomfortably on string instruments. But the remaining four works, written in the last four years of Mozart’s life, are a different matter. The last string quintets from Mozart’s pen were extraordinary works, and the addition of the second viola seems to have pulled him to still greater heights. It has been suggested that Mozart wrote K515 and K516 to show King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia that he was a better composer of string quintets than Boccherini, whom the King had retained as chamber music composer to his court. There was no response, so he offered these two quintets for sale with the K406 arrangement to make up the usual set of three. K593 and K614 were written in the last year of his life. Refinement is perhaps the word that first comes to mind in discussing these performances, which are affectionate yet controlled by a cool, intelligent sensitivity. The recordings have been well transferred, and Grumiaux’s tone, in particular, is a delight to the ear.

☆

String Quartets Nos 20-22

Quatuor Mosaïques

(Naive)

The Mosaïques’ recording of the 10 mature Mozart Quartets is completed by this release‚ so it’s time to salute an outstanding achievement. Apart from the clear‚ rich sound of the period instruments and the precise‚ beautiful tuning‚ what impresses about this Mozart playing is the care for detail‚ the way each phrase is shaped so as to fit perfectly into context while having its own expressive nuances brought out clearly. This often leads the quartet to use more rubato‚ to make more noticeable breathing spaces between sentences than many other groups do.

In the first movements of both these quartets‚ for instance‚ the Mosaïques adopt a very similar tempo and tone to the Quartetto Italiano‚ but the Italians aren’t so rhythmically flexible; though the music is beautifully shaped‚ we move continually onwards at a steady pace‚ drawing attention to the overall effect. But with the Mosaïques we’re made to listen to and appreciate the significance of each detail as it unfolds. With this approach there might be a danger of sounding contrived‚ but even when adopting a mannered style‚ as in the Minuet of K499‚ the Mosaïques retain a strong physical connection with the music’s natural pulse – by comparison the Quartetto Italiano here seem a trifle heavy and humourless. The slow movements of both quartets are taken at a flowing pace‚ making possible an unusual degree of expressive flexibility‚ achieved without any sense of hurry. All repeats are made‚ including those on the Minuet’s da capo in K499. This means that the expansive K499 lasts more than 36 minutes. The longer the better‚ as far as I’m concerned. Duncan Druce (October 2001)

☆

String Quartets Nos 14, 16 & 19

Casals Quartet

(Harmonia Mundi)

Mozart’s 1785 dedication of six quartets to Haydn reads: ‘May it therefore please you to receive them kindly and to be their Father, Guide and Friend.’ Respect is clear; but when the 96-bar Andante con moto of K428 offers a strong reminder of the 96-bar Affettuoso e sostenuto of Haydn’s Op 20 No 1, also in A flat and in compound time, affection becomes implicit too. Cuarteto Casals don’t stint on tender warmth, ensemble expertly balanced and chorale-like in sonority. Yet clarity remains uppermost. An un coagulated sound is an ever-present aspect of this ensemble’s style. So is an emotional and intellectual dimension, probed through trenchant attack, elastic lines, ductile phrases and a wide dynamic range.

Not a word on ‘authenticity’ or ‘historically informed’ practices. Rather a scant regard for superficial niceties. Pick K465 to represent the Casals’ approach, the Adagio introduction unequivocal in explaining why these 22 bars of startling false relations – A flat/A, G flat/G – and grating progressions like the chromatic sforzando clashes of F sharp/G between cello and viola raised a ruckus in its day. Reach the development of the main Allegro and the tense, driving power of the playing lifts the music to another level of interpretative penetration. Most arresting of all is the slow movement, for these musicians a sequence of pain and abraded nerve-ends behind a smokescreen of Andante cantabile. Cuarteto Casals shatter a glass ceiling of historic inhibitions and camouflage nothing. Enshrined herein is a rare order of musicianship. Nalen Anthoni (Awards issue 2014)

☆

String Quartets Nos 15 & 19. Divertimento, K138

Quatuor Ebène

(Erato)

A delicately breathy sotto voce at the beginning of K421 presages promise. Often this opening isn’t inward enough and sometimes the tempo is too fast for Allegro moderato. The Quatour Ebène trust Mozart’s directive; and Otto Jahn’s belief that this dusky movement is also an ‘affecting expression of melancholy’ makes sense at this pace. Their modes of expression play a crucial role too. These musicians bend and straighten, relax and tighten with micro-dynamic changes. All are intuitively sensed and go beyond literal obedience to the written markings. Yet pulse is steady and nothing is piecemeal or dislocated. Individual character comes first though. The Minuet is very forcefully played. Constanze, who was having their first baby, thought some passages suggested birth pangs. But the Trio, in the tonic major, is slower, solicitous, with rubatos critically timed. Interpretation is always carefully thought through and heartfelt. Turn to K465 and hear the Adagio introduction paced to give the ‘false relations’ their due, the contrasts in the main Allegro properly stressed and the element of cantabile in the slow movement most lyrically expressed. Nalen Anthoni (November 2011)

☆

Violin Sonatas Nos 5, 9, 15, 18, 21, 27, 33

Alina Ibragimova vn Cédric Tiberghien pf

(Hyperion)

Call me a killjoy, but my pulse rate rarely quickens at the prospect of Mozart’s pre-pubescent music. The three childhood works on these discs – essentially keyboard sonatas with discreet violin support – go through the rococo motions pleasantly enough. But amid the music’s chatter and trickle, only the doleful minore episode in the minuet finale of K30 and the carillon effects in the corresponding movement of K14 (enchantingly realised here) offer anything faintly individual. Still, it would be hard to imagine more persuasive performances than we have here from the ever-rewarding Tiberghien-Ibragimova duo: delicate without feyness, rhythmically buoyant (Tiberghien is careful not to let the ubiquitous Alberti figuration slip into auto-ripple) and never seeking to gild the lily with an alien sophistication.

The players likewise bring the crucial Mozartian gift of simplicity and lightness of touch (Ibragimova’s pure, sweet tone selectively warmed by vibrato) to the mature sonatas that frame each of the two discs. It was Mozart, with his genius for operatic-style dialogues, who first gave violin and keyboard equal billing in his accompanied sonatas; and as in their Beethoven sonata cycle (Wigmore Hall Live), Tiberghien and Ibragimova form a close, creative partnership, abetted by a perfect recorded balance (in most recordings I know the violin tends to dominate). ‘Every phrase tingles,’ I jotted down frivolously as I listened to the opening Allegro of the G major Sonata, K301, truly con spirito, as Mozart asks, and combining a subtle flexibility with an impish glee in the buffo repartee.

Tiberghien and Ibragimova take the opening Allegro of the E minor Sonata, K304, quite broadly, emphasising elegiac resignation over passionate agitation. But their concentrated intensity is compelling both here and in the withdrawn – yet never wilting – minuet. Especially memorable are Ibragimova’s chaste thread of tone in the dreamlike E major Trio, and Tiberghien’s questioning hesitancy when the plaintive Minuet theme returns, an octave lower, after the Trio.

In the G major Sonata, K379, rapidly composed for a Viennese concert mounted by Archbishop Colloredo just before Mozart jumped ship, Tiberghien and Ibragimova are aptly spacious in the rhapsodic introductory Adagio (how eloquently Tiberghien makes the keyboard sing here), and balance grace and fire in the tense G minor Allegro. In the variation finale their basic tempo sounds implausibly jaunty for Mozart’s prescribed Andantino cantabile, though objections fade with Tiberghien’s exquisite voicing of the contrapuntal strands in the first variation. I enjoyed the latest of the sonatas, K481, unreservedly, whether in the players’ exuberant give-and-take in the outer movements or their rapt, innig Adagio, where Ibragimova sustains and shades her dulcet lines like a thoroughbred lyric soprano. Having begun this review in grudging mode, I’ll end in the hope that these delightful, inventive performances presage a complete series of Mozart’s mature violin sonatas, with or without a smattering of childhood works. Richard Wigmore (May 2016)

☆

Violin Sonatas Nos 27, 32 & 35

Christian Tetzlaff vn Lars Vogt pf

(Ondine)

This disc brings together two musicians absolutely at the top of their game and with long experience of working together, as the easy dialogue between them amply demonstrates. High points abound: the way Tetzlaff withdraws his sound to a whisper in the long, sinewy lines of the Andante of K454; the minor-key passage in the same movement, a tragedy no less profound for being fleeting. At the other end of the emotional spectrum is the scintillating interaction of the two in the Presto of K526. This sonata, one of Mozart’s remarkable A major creations, came in the wake of personal tragedy, following the death not only of his father but also his friend, the gamba player and composer Carl Friedrich Abel, to whose memory the work is dedicated. It’s a creature of great changeability, attaining an almost hymnic intensity in the slow movement. That is especially evident in the visionary playing of Mark Steinberg with Mitsuko Uchida (a recording that should be in every home, to my mind, disappointing only for the fact that there has been no follow-up), where every yearning key-change is luminously coloured. The tragedy is perhaps more restrained in the new version, Tetzlaff’s tone warmer a degree or two than Steinberg’s, though the way he uses vibrato for expressive effect is compelling.

The reading of the earlier K379 is just as thoughtful, the opening movement achieving a more ethereal quality than Podger and Cooper, Vogt arguably the more imaginative keyboard player. It’s the hyper-reactivity between the two players that is a constant delight, as witness their subtle way of varying repeats. And the variation-form finale on a simple rococo-ish theme is entrancing, each one piquantly characterised without exaggeration. A delight from beginning to end. Harriet Smith (February 2013)

☆

Piano Quartets

Paul Lewis pf Leopold String Trio

(Hyperion)

There have been several excellent recordings recently of these two works, mostly on period instruments. Here’s another, on modern instruments, and with performances quite out of the ordinary. These are unusually expansive works, their first movements each close on 15 minutes’ music, prolific in their thematic matter and richly developed. They demand playing that shows a grasp of their scale, playing that makes plain to the listener the shape, the functional character of the large spans of the music.

Paul Lewis and the Leopold String Trio excel in this, with their feeling for its structure and its tension: I am thinking primarily of the first movement of the G minor, and especially of its great climax at the end of the development section, which is delivered with a power and a sense of its logic that are compelling. It is in fact clear from the opening that this is a performance to reckon with, exemplified by its carefully measured tempo, its poise and its subtle handling of the balance between strings and piano. There is a great deal of variety from Lewis in matters of touch and articulation, and much refinement of detail: the shades of meaning in the shifts between major and minor, and in the often chromatic harmony, do not escape him and his colleagues. The Andante is unhurried, allowing plenty of time for expressive detail; and the darker colours within the finale, for all its G major good cheer, are there too.

The spacious and outgoing E flat work is no less sympathetically done, with plenty of feeling for its special kind of broad lyricism; I particularly relished the gently springy rhythms and the tenderness of the string phrasing in the first movement, and Lewis’s beautifully shaped phrasing in the Larghetto. A real winner, this disc: warmly recommended. Stanley Sadie (October 2003)

☆

Sonata for Two Pianos, K448

Radu Lupu, Murray Perahia pfs

(Sony)

How lucky we are that the two greatest pianists of their generation, Murray Perahia and Radu Lupu, are firm friends and that they have collaborated in recording two pieces that are arguably the most successful examples of their respective genres (the Schubert is for piano duet; the Mozart for two pianos). Whether it is in the perfectly crafted busy activity of the Allegro con spirito first movement of the Mozart or the introspective and soulful depth of the Schubert, the players find a unanimity of vision. One is not so much conscious of dialogue-like interplay, but more of them blending to play as one instrument.

The fine CBS recording has entirely captured the subtle inflections of detail, especially in the artists' irreproachable balance. Taken from a live performance at The Maltings, matters of ensemble, which usually defeat the Mozart Sonata, are judged to perfection. After the double bar of the slow movement Lupu and Perahia become lost in each other's thoughts and the effect is overwhelmingly beautiful. James Methuen-Campbell (March 1986)

☆

Keyboard Music, Vol 7

Kristian Bezuidenhout fp

(Harmonia Mundi)

Mozart’s solo keyboard music inhabits a somewhat isolated corner. Great Mozartians from Clifford Curzon to Alfred Brendel to Clara Haskil left surprisingly few recordings of the solo sonatas and variations, which is why Kristian Bezuidenhout’s mandate to record all of them on fortepiano for Harmonia Mundi catches the attention. Hearing the discs themselves, one can hardly take one’s ears off the performances because they go so far inside the music and reverse much of what you thought you knew.

Bezuidenhout seems to piggyback lesser works (variations) on to major ones (sonatas) by juxtaposing them together, paired according to similar chronology, revealing moments of synchronicity as well as dramatic leaps in Mozart’s evolution, such as on Vol 7 when the 1773 Six Variations on ‘Mio caro Adone’ in G major, K180, are followed, in 1774, by the gargantuan theme-and-variations final movement of the Piano Sonata in D major, K284, showing Mozart working with an invention and rigour that almost sound like another composer. Elsewhere, though, Mozart’s freewheeling variations, at least in these performances, are doorways into the composer’s psyche in ways that the more formal, polished sonatas are not. The variations were like Mozart’s secret garden, offering glimpses of his improvisatory spirit. Dare I say that Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations came to mind repeatedly in these three volumes?

‘When Mozart played a simple scale,’ wrote Wanda Landowska, quoting the composer’s contemporaries, ‘it became transformed into a cavatina.’ That sums up the Bezuidenhout difference. His typical Mozartian attributes include firm command of structure, great instincts for sympathetic tempi and a technique refined enough to get at the tiniest details – in contrast to Paul Badura-Skoda’s more forceful but generalised fortepiano sonorities (Gramola). More distinctively, Bezuidenhout’s elastic tempi give him room to probe for meaning but also allow panache that’s so much a part of Mozart’s buoyant temperament and prompts some delightfully elongated final cadences. Not only does one hear the notes with more transparency than on a modern instrument but one also gets a stronger sense of Mozart’s larger world. Bezuidenhout’s stealth weapon, though, may be the unequal temperament of his copy of an 1805 Anton Walter instrument. The popular notion that equal temperament reigned exclusively after JS Bach just isn’t true. Experiments with alternative tuning – I’m thinking of Peter Serkin playing late Beethoven – can be colouristic revelations, which is also true of Bezuidenhout. So if you can only afford one volume of this series, which would it be? I refuse to say. Hear them all. David Patrick-Stearns (February 2015)

☆

Piano Sonatas Nos 7, 11, 15 & 18

Christian Blackshaw pf

(Wigmore Hall Live)

Hoist with my own petard, I think. Reviewing Igor Levit’s Bach/Beethoven/Rzewski Variations (11/15), I rashly concluded that I would be lucky to hear as fine a piano recording this year (meaning Gramophone Award year, rather than calendar year, incidentally). And, lo and behold, here is one.

Christian Blackshaw’s Mozart is a known quantity, of course, and I doubt whether any of the superlatives below hasn’t been applied to the previous three volumes in his Wigmore Hall Live series. But permit me to join the chorus of acclaim for his elegance of phrasing, limpid tone quality (captured in a demonstration-quality recording), tastefulness of nuance and ornamentation, and imaginative response to harmony and character. Every tiniest detail here is thought through, and only the most painstaking forensics would find the slightest fault in the fingerwork (a very few bass notes don’t quite speak, and even more rarely an ornament is less than silky smooth, if you want to know). Yet nothing is fetishised. Perfection – or something very close to it – is in the service of freedom.

As Blackshaw himself notes, ‘the sonatas resemble mini-operas’. But how to apply that insight with discretion and variety, with humanity but without histrionics, is a rare gift. Blackshaw is one of the few who know how to make the music sing and dance without making a song and dance of it. And alongside operatic eloquence, his treatment of the surrounding texture suggests the civilised conversation and wit of Mozart’s wind serenades.

Never have the 16 minutes of the first movement of the A major Sonata (K331) passed more graciously, for me at least, and the acknowledgement of the Adagio marking for the fifth variation is exquisitely tasteful. At the end of the C major Sonata (K309), how delectable is the tiny relaxation of pulse to allow the lowest register to speak. How subtly weighted are the fp accents in the slow movement of the F major, and how perfectly adapted to their harmonic environment. Even the wonderful Uchida sounds occasionally a fraction effortful by comparison.

Regretfully, I have to note that this volume completes Blackshaw’s survey of the sonatas. I can only hope for a set of the fantasies, rondos and miscellanea so that I can continue this paean. David Fanning (January 2016)

☆

Piano Sonatas Nos 1–18

Mitsuko Uchida pf

(Philips)

By common consent, Mitsuko Uchida is among the leading Mozart pianists of today, and her recorded series of the piano sonatas won critical acclaim as it appeared and finally Gramophone Awards in 1989 and 1991. Here are all the sonatas, plus the Fantasia in C minor, K475, which is in some ways a companion piece to the sonata in the same key, K457. This is unfailingly clean, crisp and elegant playing, that avoids anything like a romanticised view of the early sonatas such as the delightfully fresh G major, K283. On the other hand, Uchida responds with the necessary passion to the forceful, not to say angst-ridden, A minor Sonata, K310. Indeed, her complete series is a remarkably fine achievement, comparable with her account of the piano concertos. The recordings were produced in the Henry Wood Hall in London and offer excellent piano sound; thus an unqualified recommendation is in order for one of the most valuable volumes in Philips's Complete Mozart Edition. Don't be put off by critics who suggest that these sonatas are less interesting than some other Mozart compositions, for they're fine pieces written for an instrument that he himself played and loved.

☆

Complete Piano Sonatas

Daniel-Ben Pienaar

(Avie)

Daniel-Ben Pienaar couldn’t have begun better, not by playing but by saying, “It is inescapable that a performance practice for these works that engages the instrument’s full expressive potential needs to look beyond easy categories of ‘authentic’, or ‘modern’ or ‘historically informed’”. Quite – but that’s not all, so do read his booklet-note first. One factor strikes immediately: there is not a whiff of bygone reverential, even obsequious attitudes to Mozart that still cast faint shadows among some pianists. Pienaar is therefore “modern” in his discernment of the music. But – how about this for a 19th-century throwback? – Pienaar de-synchronises his hands, though selectively so. Effects are clear in, for example, the Fantasia, K475. The fractional hiatus between left and right underpins the harmony in the first and third bars; and a similar hiatus in the D major section (2'25") lends added expression to its contrasting calmness. The staggered articulation is no mere anachronism. It becomes a subtle aspect of a range of expression Pienaar uses to penetrate music “very rich in activity, rich in personality and topoi”. Point and purpose explained. And totally disdained is “the facile stereotype of Mozart as the epitome of elegance”. Of the utmost importance in conveying convictions is Pienaar’s strong, independent left hand. It tightens harmonic tension and supports rather than accompanies treble lines. Be it high drama or lyrical contemplation, Pienaar scans phrases with a fluidity that releases the music from rhythmic inertia. Ignore the odd insignificant pianistic smudge, because keyboard prowess is formidable. But as his performance of the Alla turca Sonata, K331, shows, technique isn’t allowed to edge ahead of emotional and intellectual depth. A much-mistreated piece emerges in a different light. Pienaar pays attention to the oft-forgotten grazioso element in the first movement, eschews metrical stiffness in the Minuet, yields to the Trio’s distinctive flow and refuses to turn the March into a janissary bash. Extend such thoughtful, profound probity to the whole set and you have interpretations where within the letter critically observed, a numinous potency breaks free. Momentous Mozart.

☆

Piano Sonatas Nos 8 & 15

Richard Goode pf

(Nonesuch)

There’s nothing more demanding of mind and finger, heart and hand, than a Mozart programme such as this, which includes two of the greatest sonatas and the A minor Rondo. Absolutely no margin for error or insufficiency, nor indeed for anything at all approximate or generalised. It’s given to very few to play Mozart as well as Richard Goode, who seems to me to pitch the rhetoric just right and sustain an ideal balance of strength and refinement. Pitching rhetoric so that one is constantly persuaded isn’t a question of getting it in the right ball-park but of defining character with absolute precision and making eloquence speak as well as sing. With Goode, the music couldn’t be any other way, not at this moment. The smallest units have been thought about, judged in relation to before-and-after and the long term, and then released into the air, beyond the confines of the instrument.

It’s quite big playing and I like that, too, the range of sonority appropriate to the A minor Sonata, K310, in particular; and I can’t recall a recent recording of it which realises so well the sharp contrasts, the cross-cut abutments of dynamics, which are such a striking feature in all three movements. One of Goode’s characteristics is a touch of urgency that has nothing to do with impetuosity or agitation of the surface but rather with a projection of the discourse in the sense of carrying it forward and making us curious about what will happen next. And in the presto finale, where Brendel is choppy and rather slow, Goode is exciting as well as articulate and wonderfully adept at getting from one thing to another.

There’s little to choose between these players in the composite F major Sonata, K533/494. Brendel is at his finest in the dark, far-reaching middle movement; both of them relish the challenge of characterising the multifariousness of the first, with Brendel’s pianism at the service of the drama but perhaps the plainer of the two in dealing with the intricacies of the counterpoint. Goode is especially convincing in the last movement, Mozart’s revision of an earlier piece sometimes considered too lightweight to function as a finale; I don’t think you would have a doubt about it here.

He gives you the overview, too, often powerfully. While admiring the flux of intensities, dynamics, shapes and colours he sets before you in the Rondo, I wondered three-quarters of the way through whether the totality was going to achieve enough weight. But the coda is to come – passionate and desolate, a close without parallel in Mozart’s instrumental music – and at moments such as this you can be assured that Goode will surprise and certainly not disappoint. The shorter pieces, enterprisingly chosen, set off the great works admirably. Exceptional sound throughout – like the playing, quite out of the ordinary run. Stephen Plaistow (June 2005)

☆

Mass in C minor

Carolyn Sampson (soprano), Olivia Vermeulen (alto), Makoto Sakurada (tenor), Christian Immler (bass) Bach Collegium Japan / Masaaki Suzuki

(BIS)

Period-instrument C minor Masses get better and better. The bar was set in the mid 1980s by Gardiner and Hogwood, then raised in the new millennium by the likes of McCreesh, Krivine and Langrée. This new recording from Japan, which joins Suzuki’s scholarly and startling Requiem, is fully worthy to join them. Reviewing the Requiem (1/15), I was disappointed that the acoustic and engineering blurred the inner voices, obliterating Mozart’s (or Süssmayr’s, Eybler’s or Suzuki Jnr’s) counterpoint. Here that problem is largely avoided in a similarly grand acoustic: that, and the fact that the C minor Mass is a far more vocally orientated piece than the Requiem.

The choir are well drilled and the two female soloists are matched as well as any on disc (see my Collection on the work, 6/13). Carolyn Sampson takes the bulk of the soprano solos (the ‘Laudamus’ is taken by the second soprano, Olivia Vermeulen, as is traditional) and does so with the lithe coloratura, rich, silky tone and innate identification with this music familiar from her sacred Mozart collection with The King’s Consort (Hyperion, 5/06), and intertwines memorably with Olivia Vermeulen in the duet and trio of the Gloria. Suzuki is no speed merchant (a full minute slower than Langrée in the Kyrie, for example), and maintains the through line in more strenuous movements such as the ‘Qui tollis’ and the ‘Cum Sancto Spiritu’ fugue that closes the Gloria. He takes his time especially in the ‘Et incarnatus est’, its beautiful pastoral scene spun out mesmerisingly by Sampson.

The edition used of this tantalisingly incomplete work is that by Franz Beyer, published in 1989. There is nothing here to discombobulate the general listener; however, those for whom such matters are important will wish to know that there are no (editorial) trumpets in the ‘Credo’ or horns in the ‘Incarnatus’, whose new string parts are perhaps more active than those in the more usual HC Robbins Landon completion. (Beyer also contrived an Agnus Dei from the music of the Kyrie but that is not recorded here.) As the only other recording of this edition is Harnoncourt’s, whose peculiar balance between voices and instruments is a sticking point, it is worthwhile to hear Beyer’s work on this disc.

Sampson is once again the soloist in the popular Exsultate, jubilate, the treat here being a parallel recording of the opening aria in the ‘Salzburg’ version, which boasts a different text and flutes instead of oboes. As a package, the disc as a whole is certainly a winner; the Mass easily ranks alongside the period-instrument benchmarks. David Threasher (December 2016)

☆

Requiem

Joanne Lunn, Rowan Hellier, Thomas Hobbs and Matthew Brook (soloists) Dunedin Consort / John Butt

(Linn)

Purely on grounds of performance alone, this is one of the finest Mozart Requiems of recent years. John Butt brings to Mozart the microscopic care and musicological acumen that have made his Bach and Handel recordings so thought-provoking and satisfying.

As with all of Butt’s recordings, however, this Mozart Requiem is something of an event. The occasion is the publication of a new edition – by David Black, a senior research fellow at Homerton College, Cambridge – of the ‘traditional’ completion of this tantalisingly unfinished work, of which this is the first recording. Süssmayr’s much-maligned filling-in of the Requiem torso has lately enjoyed a resurgence in its acceptance by the scholarly community – not that it has ever been supplanted in the hearts and repertoires of choral societies and music lovers around the world. The vogue for stripped-back and reimagined modern completions is on the wane and Süssmayr’s attempt, for all its perceived inconsistencies and inaccuracies, is once again in favour in the crucible of musicological criticism. After all, as Black points out in the preface to his score, ‘Whatever the shortcomings of Süssmayr’s completion, it is the only document that may transmit otherwise lost directions or written material from Mozart’.

Black has returned to the earliest sources of the work: Mozart’s incomplete ‘working’ score, Süssmayr’s ‘delivery’ score and the first printed edition of 1800, which even so soon after the work’s genesis was already manifesting accretions and errors that place us at a further remove from Mozart’s intentions. For all the textual emendations this engenders, the actual difference as far as the general listener is concerned is likely to be minimal; while we Requiemophiles quiver with delight at each clarified marking, to all intents and purposes what is presented here is the Mozart Requiem as it has been known and loved for more than two centuries.

It is Butt’s minute attention to these details, though, that makes this such a thrilling performance. He fields a choir and band of dimensions similar to the forces at the first performance of the complete work on January 2, 1793, little over a year after Mozart’s death, and the effect is, not unexpectedly, to wipe away the impression of a ‘thick, grey crust’ that was felt so palpably by earlier commentators on the work. Listen, for example, to Mozart’s miraculous counterpoint at ‘Te decet hymnus’ in the Introit or Süssmayr’s rather more clumsy imitation in the ‘Recordare’, and hear how refreshingly the air circulates around these potentially stifling textures. Butt’s outlook on the work is apparent from the very beginning: the gait of the string quavers is more deliberate than limping in the first bar, and this purposefulness returns in movements such as the ‘Recordare’ and ‘Hostias’. The extremes of monumentality and meditativeness in the Requiem are represented perhaps by Bernstein and Herreweghe respectively; Butt steers a course equidistant between the two without compromising the work in its many moments of austerity or repose. Paradoxically, Butt’s fidelity to the minutiae of the score allows him the freedom to shape a performance of remarkable cumulative intensity, so that the drama initiated in the driving ‘Dies irae’ reaches a climax and catharsis in the ‘Lacrimosa’ and is recalled in the turbulent Agnus Dei.

The choir is of only 16 voices, from which the four soloists step out as required. Blend and tuning are of an accuracy all too rarely heard, even in this golden age of British choral singing. Soprano Joanne Lunn’s tone is well nourished, with vibrato deployed judiciously to colour selected notes or phrases; of the other soloists, Matthew Brook’s bass responds sonorously to the sounding of the last trumpet (in German ‘die letzte Posaune’ – the last trombone) in the ‘Tuba mirum’. Instrumental sonority, too, is meticulously judged: hear especially the voicing of the brass-and-wind chords during bridge passages in the ‘Benedictus’ or the shifting orchestral perspectives of the ‘Confutatis’.

The couplings are also carefully considered. The first is Misericordias Domini, an offertory composed in 1775 of which Mozart had a set of parts copied in 1791. Sharing with the Requiem its key and a gleeful exploitation of contrapuntal techniques, it piquantly demonstrates the advance in Mozart’s church style during the last 16 years of his life.

The disc closes with what purports to be a re-enactment of an even earlier ‘first performance’ of the Requiem. While the 1793 Vienna concert is well documented, recent research has suggested that the Requiem (or at least some of it) was performed in a memorial to Mozart on December 10, 1791 – only five days after his death. Given the partial state of the work (only the Introit was complete in Mozart’s hand), it is supposed that this performance consisted of the Introit and the ensuing Kyrie fugue, for which an amanuensis filled in the doubling woodwind parts. That performance is hypothesised here with slimmed-down vocal and string parts, and with trumpets and drums missing from the Kyrie (on the presumption that the parts hadn’t been provided by that time). Starker still than the larger performance, this telling appendix offers a tantalising glimpse of the music that might have been played by Mozart’s friends and students as they struggled to come to terms with their loss. David Threasher (May 2014)

☆

Requiem

Margaret Price, Trudeliese Schmidt, Francisco Araiza, Theo Adam; Staatskapelle Dresden / Peter Schreier

(Philips)

Instrumentalists often become conductors, and great ones; yet the number of singers who have successfully taken up the baton is remarkably small; but on the evidence of this recording of Mozart's Requiem, the distinguished German tenor Peter Schreier (who was born in 1935) ranks high in that select company. He is, of course, closely associated with the tenor roles in Mozart's operas, and he must have sung as a soloist in the Requiem on countless occasions (he recorded it for Erato with Michel Corboz on STU70943, 6/67), but although he has been active as a conductor since 1970 he has rarely featured in this capacity on records issued in this country.

The fact that he knows the score inside out and that he loves the music passionately, shines through the whole performance: I can think of few, if any, live or on records, that have struck me as being so totally committed to the spirit of this great work, or have made it sound like a finished masterpiece—despite the fact that Mozart did not live long enough to write the score out in full, and that it was completed by his pupil Sussmayr. He is, as every singer should be, especially sensitive to the words, as well as to the music: one instance is his quite extraordinarily perceptive handling of the Recordare, in which the four soloists for once sing as if they really understand every word and inflection of the Latin text. The solo quartet is unusually fine and well balanced, and if I say that Margaret Price sings the prominent soprano part better than I can ever remember having heard it sung, this is in no way meant to disparage the equally beautiful singing of Trudeliese Schmidt, Francisco Araiza and Theo Adam. The Leipzig Radio Chorus and the Dresden State Orchestra provide splendid support and Philips's digital recording is uncannily vivid.

There is no shortage of recordings to compare this new one with. Of the two listed above, Barenboim's on HMV is the more dramatic, Marriner's (Argo) the more restrained. Both have their good points, and both have first-rate soloists, chorus and orchestra (Barenboim has Sheila Armstrong, Dame Janet Baker, Nicolai Gedda, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the John Alldis Choir and the ECO; Marriner has Ileana Cotrubas, Helen Watts, Robert Tear, John Shirley-Quirk and the ASMF Chorus and ASMF). But, for me, Schreier's performance is a revelation, and his recording is the one that I would take to my desert island if I had the choice. Robin Golding (March 1984)

☆

Così fan tutte

Sols incl Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig, Giuseppe Taddei; Philharmonia Orchestra / Karl Böhm

(Warner Classics)

Così fan tutte is the most balanced and probing of all Mozart’s operas, formally faultless, musically inspired from start to finish, emotionally a matter of endless fascination and, in the second act, profoundly moving. It has been very lucky on disc, and besides this delightful set there have been several other memorable recordings. However, Karl Böhm’s cast could hardly be bettered, even in one’s dreams. The two sisters are gloriously sung – Schwarzkopf and Ludwig bring their immeasurable talents as Lieder singers to this sparkling score and overlay them with a rare comic touch. Add to that the stylish singing of Alfredo Kraus and Giuseppe Taddei and the central quartet is unimpeachable. Walter Berry’s Don Alfonso is characterful and Hanny Steffek is quite superb as Despina. The pacing of this endlessly intriguing work is measured with immaculate judgement. The emotional control of the characterisation is masterly and Böhm’s totally idiomatic response to the music is arguably without peer.

☆

Così fan tutte

Sols incl Miah Persson, Anke Vondung, Ainhoa Garmendia, Topi Lehtipuu; Glyndebourne Chorus; Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment / Iván Fischer

(Opus Arte DVD/Blu-ray)

Since 1934 when Glyndebourne revived this then-neglected work and began its run of success it has presented a succession of exemplary stagings all within the parameters of da Ponte’s libretto. When this, the latest, was produced it was universally hailed: as faithful a representation of the equivocal comedy as one could wish. That’s confirmed by this DVD.

Both Despina and Alfonso are played traditionally and with notable brio by Garmendia and Rivenq. The delightful Persson and Vondung make a wholly believable and vocally attractive Fiordiligi and Dorabella, and deliver their music in ideal Mozartian tone and style. Similarly Lehtipuu is a charming and wide-eyed Ferrando and Pisaroni a warm-voiced and personal Guglielmo. They both woo with seductive charm.

As reviews at the time reported, Fischer conducts with an unassumingly correct sense of timing and has the inestimable advantage of the OAE’s period instruments. Alan Blyth (June 2007)

☆

Don Giovanni

Sols incl Rodney Gilfry, Luba Orgonasova, Charlotte Margiono, Christoph Prégardien, Ildebrando d’Arcangelo; Monteverdi Choir; English Baroque Soloists / Sir John Eliot Gardiner

(Archiv Produktion)

Gardiner’s set has a great deal to commend it. The recitative is sung with exemplary care over pacing so that it sounds as it should, like heightened and vivid conversation, often to electrifying effect. Ensembles, the Act 1 quartet particularly, are also treated conversationally, as if one were overhearing four people giving their opinions on a situation in the street. The orchestra, perfectly balanced with the singers in a very immediate acoustic, supports them, as it were ‘sings’ with them. That contrasts with, and complements, Gardiner’s expected ability to empathise with the demonic aspects of the score, as in Giovanni’s drinking song and the final moments of Act 1, which fairly bristle with rhythmic energy without ever becoming rushed. The arrival of the statue at Giovanni’s dinner-table is tremendous, the period trombones and timpani achieving an appropriately brusque, fearsome attack. Throughout this scene, Gardiner’s penchant for sharp accents is wholly appropriate; elsewhere he’s sometimes rather too insistent. As a whole, tempos not only seem right on their own account but also, all-importantly, carry conviction in relation to each other. Where so many conductors today are given to rushing ‘Mi tradì’, Gardiner prefers a more meditative approach, which allows his soft-grained Elvira to make the most of the aria’s expressive possibilities.

Rodney Gilfry’s Giovanni is lithe, ebullient, keen to exert his sexual prowess; an obvious charmer, at times surprisingly tender yet with the iron will only just below the surface. Suave and appealing, delivered in a real baritone timbre, his Giovanni is as accomplished as any on disc. Ildebrando d’Arcangelo was the discovery of these performances: this young bass is a lively foil to his master and on his own a real showman, as ‘Madamina’ indicates, a number all the better for a brisk speed. Orgonasova once more reveals herself a paragon as regards steady tone and deft technique – there’s no need here to slow down for the coloratura at the end of ‘Non mi dir’ – and she brings to her recounting of the attempted seduction a real feeling of immediacy. As Anna, Margiono sometimes sounds a shade stretched technically, but consoles us with the luminous, inward quality of her voice and her reading of the role, something innate that can’t be learnt.

Nobody in their right senses is ever going to suggest that there’s one, ideal version of Don Giovanni; the work has far too many facets for that, but for sheer theatrical élan complemented by the live recording, Gardiner is among the best, particularly given a recording that’s wonderfully truthful and lifelike. Alan Blyth (August 1995)

☆

Don Giovanni

Sols incl Waechter, Sutherland, Schwarzkopf; Philharmonia Orchestra / Carlo Maria Giulini

(Warner Classics)

At last. The 1959 Giulini Don Giovanni has been digitally remastered and made available on CD. Philip Hope-Wallace, reviewing the original release, thought that it was worth a year at a foreign university. Well, I don't know if I'd go that far; but it is extremely difficult to choose between this and the Davis performance on Philips for non-stop momentum born of deep understanding of the musical expression of character and dramatic motivation.

There is no doubt that the orchestral playing here is unsurpassed. From the depth and precision of the opening chords to the fugitive spirit of dance which no one else quite captures, the Philharmonia under Giulini become a second cast on their own. So often the tiniest detail – the weight of a chord, the length of a silence, the linking curve of a phrase, the parting of the inner voices of the strings – stage-manages the drama more shrewdly than a good many theatre directors ever do. That having been said, I find Davis's pacing marginally more exciting. Giulini does, one feels, occasionally hold back to allow a voice its moment of glory; and the Act 1 finale hasn't quite that thrilling inexorability as the dance hurtles from form to chaos.

The presence of Dame Joan Sutherland does have its drawbacks as well as its glory. Her Donna Anna is never quite a ''furia disperata''; the comparative weakness of her lower register and her lack of real impulse in phrasing make her as a weak match for Schwarzkopf's Elvira as Te Kanawa's Elvira is for Arroyo's superb Anna for Davis. Only Haitink on EMI, it seems, with Vaness and Ewing, has a pair equally matched, at least in dramatic credibility: Glyndebourne's team casting is, of course, its great strength.

Schwarzkopf's Elvira, together with the orchestral playing, is the glory of this Don Giovanni. Listen to their relationship in ''In quali eccessi'': it could hardly be more potent, more intensely Mozartian. She understands the rhythmic and melodic psychology of her every second on stage. So does this Don Giovanni: though Waechter's thrusting physicality and diabolic laughter leave us just short of the sheer fascination of Wixell's hunter (Davis) or Allen's chilling seducer (Haitink).

The casting of the smaller parts doesn't make for such vibrant theatre as in either Davis or Haitink; but the care originally lavished on the production by Walter Legge is celebrated in remastering which cuts out glare and distortion, while losing none of the depth and perspective which belong uniquely to Giulini's reading. Hilary Finch (December 1987)

☆

Don Giovanni

Sols incl Allen, Verness, Ewing; London Philharmonic Orchestra / Bernard Haitink

(EMI/Warner Classics)

By general consent, the performances of Don Giovanni in Sir Peter Hall's production at Glyndebourne in 1982 were considered profoundly satisfying, and therefore a special achievement in a work so hard to bring off both on stage and on the gramophone. Now that achievement is mostly confirmed in a recording that is definitely the peer of those that have gone before and possibly their superior in several respects. Giovanni is certainly the most recorded of Mozart's operas, so the work must be much in demand among collectors who, like Giovanni in his search for women, seem unsatisfied by the available choice.

They ought to find the new version solving many of their difficulties. In the first place, as with so many recommendable ones of operas these days, it has the best of both worlds: the experience of recent stage performances refined under studio circumstances – including one significant change of cast. Then it has in Haitink as cogent a conductor as any who have gone before. In many respects he recalls the direct, unaffected, judicious conducting of Fritz Busch, one of his predecessors as Glyndebourne's Music Director (Busch's famous 1936 recording is still to be had – EMI, 3/83). He is as much aware as Bohm of the importance of rhythmic impetus and natural flow, also of vital detail – such as the wind gurglings in ''Meta di vuoi''.