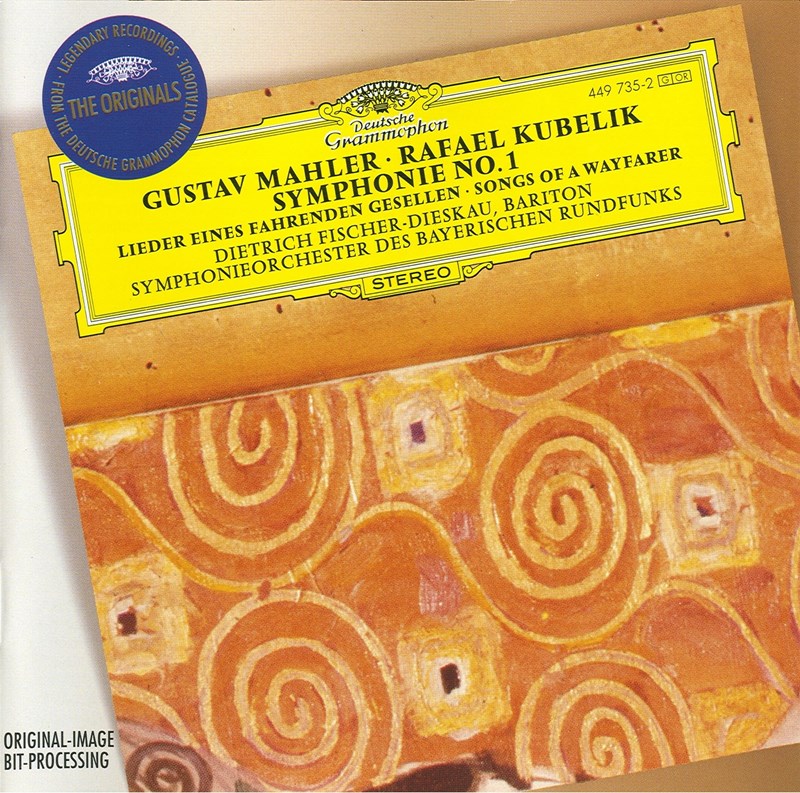

Symphony No 1

Symphony No 1. Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau bar Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Rafael Kubelík (DG)

On the first appearance of the symphony in 1968, Deryck Cooke observed that Rafael Kubelík was “essentially a poetic conductor and he gets more poetry out of this symphony than any of the other conductors who have recorded it”. Bruno Walter was, he felt, Kubelík’s only rival in this regard and he was much taken with the “natural delicacy and purity” of the interpretation. Unlike Walter, Kubelík takes the repeat of the first movement’s short exposition. Strange, then, that he should ignore the single repeat sign in the Landler when he seems so at ease with the music. Notwithstanding a fondness for generally brisk tempos in Mahler, Kubelík is never afraid of rubato here, above all in his very personally inflected account of the slow movement. This remains a delight. The finale now seems sonically a little thin, with the trumpets made to sound rather hard-pressed and the final climax failing to open out as it can in more modern recordings. The orchestral contribution is very good even if absolute precision isn’t guaranteed. In the first movement we do not get genuinely quiet playing from the horns at 9'30'' whereupon the active part of the development is rather untidily thrust upon us.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s second recording of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen has worn rather less well, the spontaneous ardour of his earlier performance (with Furtwängler and the Philharmonia – EMI, 6/87) here tending to stiffen into melodrama and mannerism. There is of course much beautiful (if calculated) singing and he is most attentively accompanied, but the third song, “Ich hab’ ein gluhend Messer”, is implausibly overwrought, bordering on self-parody. By contrast, Kubelík’s unpretentious, Bohemian approach to the symphony remains perfectly valid. A corrective to the grander visions of those who conduct the music with the benefit of hindsight and the advantages of digital technology? Perhaps.

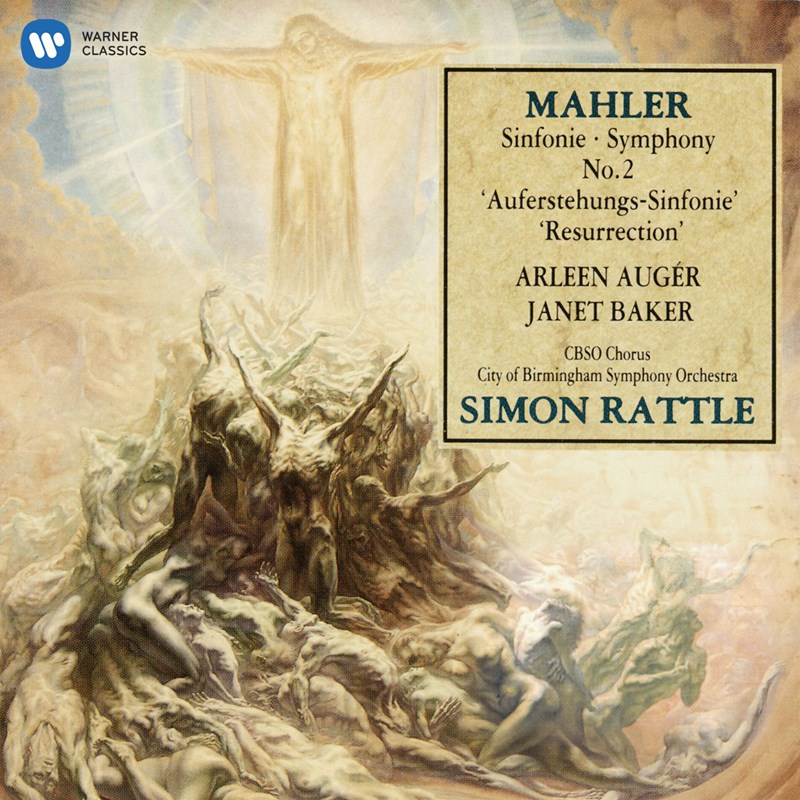

Symphony No 2

Symphony No 2

Auger sop Baker mez CBSO & Chorus / Simon Rattle (EMI / Warner Classics)

Rattle’s first – Gramophone Award-winning – recording of the work. Attention to dynamics is meticulous and contributes immeasurably to the splendour of the performance. Dame Janet Baker is at her most tender in ‘Urlicht’, with Arleen Auger as the soul of purity in the finale. The CBSO Chorus is magnificent. Indeed, the whole finale is an acoustic triumph.

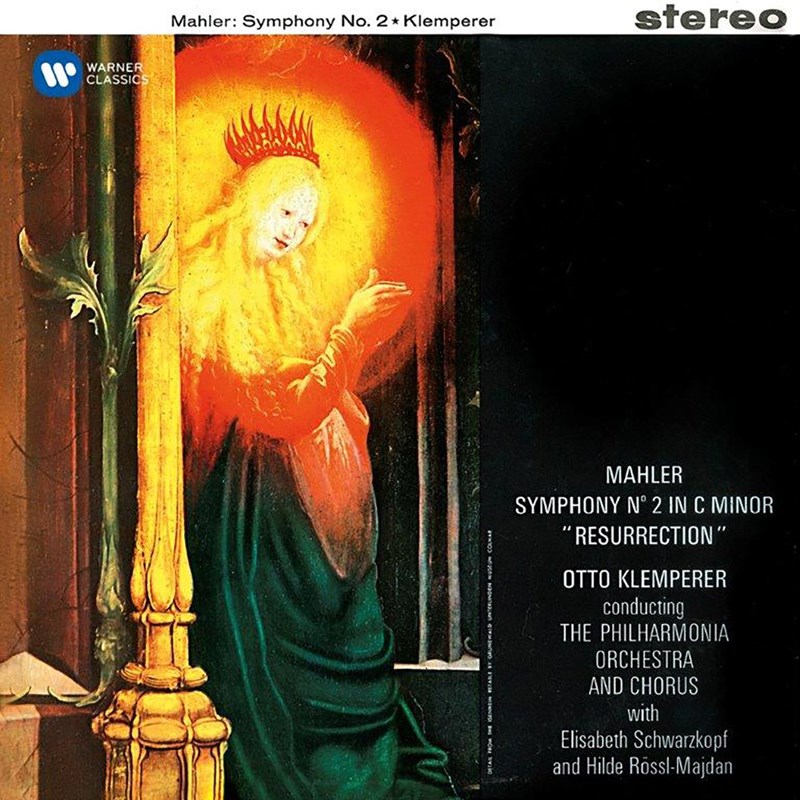

Symphony No 2

Schwarzkopf sop Rössl-Majdan mez Philharmonia and Chorus / Otto Klemperer (EMI / Warner Classics)

You miss those elements of high risk, the brave rhetorical gestures, the uncompromising extremes in Klemperer’s comparatively comfortable, down-the-line response. He knocks minutes off most of the competition (yes, it’s a fallacy that Klemperer was always slower), paying little or no heed to Mahler’s innumerable expressive markings in passages which have so much to gain from them. The finale, growing more and more momentous with every bar, possesses a unique aura. Not everyone is convinced by Klemperer’s very measured treatment of the Judgement Day march. The grim reaper takes his time but the inevitability of what’s to come is somehow the more shocking as a result.

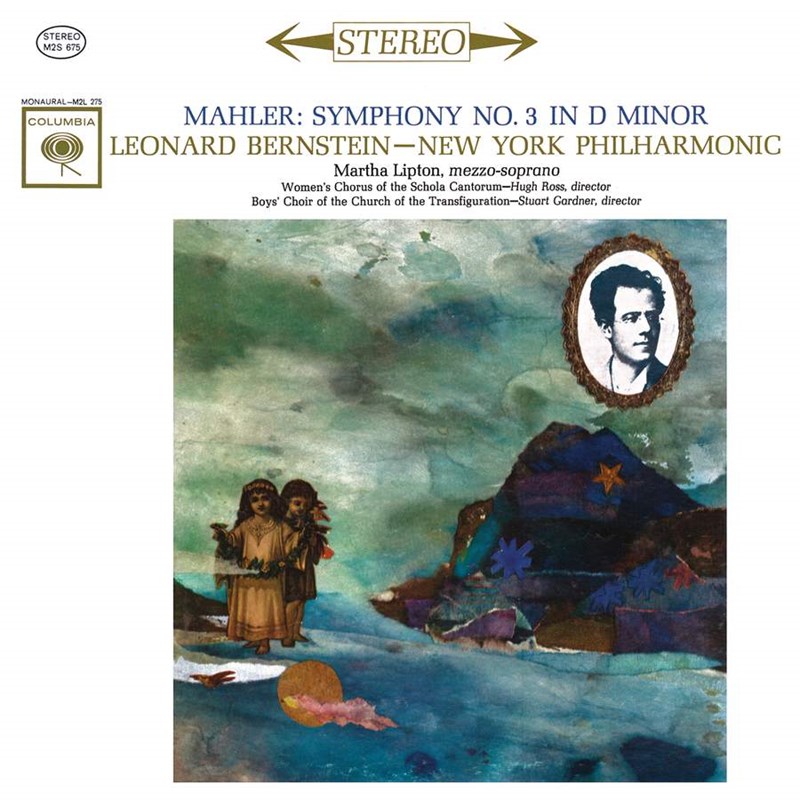

Symphony No 3

Symphony No 3

Martha Lipton; Choir of the Transfiguration; NYPO / Leonard Bernstein (Sony)

Few who experienced Bernstein’s passionate advocacy of Mahler’s musical cause in the 1960s were left untouched by it. These recordings date from those years and the flame of inspiration still burns brightly about them decades later. The CBS recordings were clearly manipulated, but the sound – at best, big and open but trenchant and analytically clear – suited Mahler’s sound world especially well. Bernstein’s account of the Third Symphony is as compelling an experience and as desirable a general recommendation now as when it first appeared. The New Yorkers are on scintillating form under the conductor they have most obviously revered in the post-war period. This is a classic account, by any standards.

Symphony No 4

Symphony No 4

Miah Persson; Budapest Festival Orchestra / Iván Fischer (Channel Classics)

What no one will deny is the amazing unanimity and precision of the playing here and the superlative quality of the sound engineering. But how to read a work that can feel brittle as well as heart-warming and graceful? Despite Iván Fischer’s eminently sane and central pacing overall, he courts controversy with inconsistencies of tone between (and individualised inflexions within) the four movements.

Some maestros choose between neo-classical modernity and old-world Gemütlichkeit. Fischer gives us both and more: he gives us instability. Rather than taking his cue from the opening bars in which the jingling sleigh bells might be construed to lose their way, Fischer mixes them down, introducing his own eccentric nuance a fraction later. He permits an oasis of exquisite repose just before the movement’s final flourish yet much of the rest is unsettling. While details unearthed are revelatory – often linear, maybe functional, certainly more than merely illustrative – the quest can seem obsessive, at odds with the sense of ease indicated by the composer. Make no mistake however, the playing has character and conviction, the divided violins enhancing transparency albeit at some expense of weight and blend. Less self-regarding or at least less wilful since the idiosyncrasies are intrinsic, the Scherzo goes wonderfully well, with solo violin and clarinets in particular excelling themselves. The slow movement is just a little pale, as if Fischer were deliberately avoiding the calculated sublimity and cushioned string tone associated with big-band performances of late Beethoven. The gates of Heaven are flung open with a great blare, possibly a bit much for home listening but replicating the immediacy of the concert hall. In the finale, Fischer achieves novelty chiefly through understatement, mindful of the need to avoid coyness at all costs. Miah Persson is ideally cast and as she invokes Saint Martha at 3'56" it’s as if we’re transported to a small village church, the organ made tangible in the exquisite treatment of the accompanying instrumental texture.

This is just one of countless imaginative touches on an exceptional hybrid SACD. That said, I’m still in two minds about it. Is Mahler’s emotive force blunted by Fischer’s careful manicure? David Gutman (April 2009)

Symphony No 5

Symphony No 5

New Philharmonia Orchestra / Sir John Barbirolli (EMI / Warner Classics)

Sir John Barbirolli’s Fifth occupies a special place in everybody’s affections: a performance so big in spirit and warm of heart as to silence any rational discussion of its shortcomings. Some readers may have problems with one or two of his sturdier tempi. He doesn’t make life easy for his orchestra in the treacherous second movement, while the exultant finale, though suitably bracing, arguably needs more of a spring in its heels. But against all this, one must weigh a unity and strength of purpose, an entirely idiomatic response to instrumental colour and texture (the dark, craggy hues of the first two movements are especially striking); and most important of all that very special Barbirollian radiance, humanity – call it what you will.

One point of interest for collectors – on the original LP, among minor orchestral mishaps in the Scherzo, were four bars of missing horn obbligato (at nine bars before fig 20). Not any more! The original solo horn player, Nicholas Busch, has returned to the scene of this momentary aberration (Watford Town Hall) and the absent bars have been ingeniously reinstated. There’s even a timely grunt from Sir John, as if in approval. Something of a classic, then; EMI’s remastering is splendid.

Symphony No 5

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Leonard Bernstein (DG)

Bernstein's tempo for the funeral march in the first movement of Mahler's Fifth Symphony has become slower in the 23 years that separate his New York CBS recording from this new one, made during a performance in Frankfurt a year ago. I think the faster tempo is nearer to Mahler's intention, but I much prefer the later interpretation as a whole. For one thing, the VPO play it much better than the NYPO of 1964, who were having a relatively bad day when the recording was made. The strings only passage at fig. 15 in the first movement, for example, is exquisitely played, so is the long horn solo in the Scherzo. And there is one marvellously exciting moment — the right gleam of trumpet tone, the Hohe-punkt, at one bar before fig. 29 in the second movement.

Best of all is Bernstein himself, here at his exciting best, giving daemonic edge to the music where it is appropriate and building the symphony inexorably to its final triumph. Thanks to a very clear and well-balanced recording, every subtlety of scoring, especially some of the lower strings' counterpoint, comes through as the conductor intended. As in the case of Sinopoli's underrated recording of this symphony (also DG), one is made aware of the daring novelty of much of the orchestration, of how advanced it must have sounded in the early years of this century. But whereas with Sinopoli this emphasis was achieved at the expense of some expressive warmth, that is far from the case with Bernstein. We get the structure, the sound and the emotion.

The Adagietto is not dragged out, and the scrupulous attention to Mahler's dynamics allows the silken sound of the Vienna strings to be heard to captivating advantage, with the harp well recorded too. It seems to me that Bernstein is strongest in Mahler when the work itself is one of the more optimistic symphonies with less temptation for him to add a few degrees more of angst. His Seventh and Fifth are great interpretations whereas I would be reluctant to include his Ninth among the really memorable accounts.

Symphony No 5

Lucerne Festival Orchestra / Claudio Abbado

Video director Michael Beyer (EuroArts)

Claudio Abbado’s Mahler Fifth is magnificent. It helps that the band is the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, that most exalted of all ad hoc ensembles, rather than the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester. It does make a difference in Lucerne to have a raft of seasoned players joining the core contingent from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. The visual dimension is stronger, too, with the option to switch to the so-called ‘Conductor Camera’ and experience Abbado from a player’s perspective. If this strikes some readers as a gimmick I can only say that I welcome it as a natural use of the new medium.

Listen without the images, though, and it quickly becomes apparent that Abbado’s previous, audio-only account (DG, subsequently revamped for SACD) is sonically superior, with greater hall ambience and less tendency for wind, brass and percussion to lose themselves in the mix. It’s not as if the conductor’s conception has changed a great deal. His Fifth has always displayed a tad less inner intensity than some of the great readings of the past but with compensating elegance and grace. Once again the famous Adagietto steals in with a magic inevitability that few have matched. Abbado’s music-making is as fine as you will find anywhere today and his admirers should be well satisfied.

Symphony No 6

Symphony No 6

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (DG)

Whatever the revolution in playing standards since January 1966, when Barbirolli conducted Mahler’s Sixth in Berlin, I can’t remember hearing a tauter, more refined performance than this, nor one that dispenses so completely with the heavy drapes of old-style Mahler interpretation. The work concluded Abbado’s first Philharmonie programme since passing the reins to Sir Simon Rattle, an occasion bound to provoke standing ovations and a little myth-making, too. Only if one discounts Celibidache’s interregnum could this be considered the first time in the orchestra’s history that a former chief had returned to direct. Now, with the music repositioned on the sunny side of the Alps and seen through the prism of the Second Viennese School, an effortless, sometimes breathtaking transparency prevails. In the first movement, Abbado’s sparing use of rubato precludes the full (de-)flowering of the ‘Alma theme’ in the Bernstein manner, and there are some curiously stiff moments in the Andante moderato, here an iridescent intermezzo quite unlike Karajan’s Brucknerian slow movement.

This may not be a Sixth for all seasons and all moods – the Berliners rarely play with the full weight of sonority long thought uniquely theirs – yet I soon found reservations falling away. For all its fine detailing, Abbado’s finale lacks nothing in intensity, with a devastating corporate thrust that may or may not have you ruing DG’s decision to include an applause track. A more serious stumbling block is the maestro’s decision to place the Scherzo third, following the lead of Del Mar, Barbirolli, Rattle and others. Purchasers of a a single disc CD version available in some parts of the world can re-programme, of course, but technical constraints for the hybrid SACD disc, available in the UK, have led DG to opt for a pair of discs containing two movements apiece. It must, however, be pointed out that the extra cost is borne by the manufacturer, not the consumer. And, apart from two curious pockets of resonance in the finale (on either side of the 10-minute mark), Christopher Alder’s team achieves a much more realistic balance than you’ll find in the conductor’s previous live Mahler issues. If a little cavernous, the effect is blessedly consistent, allowing us to appreciate that Abbado’s sweetly attenuated string sound is just as beautiful as Karajan’s more saturated sonority, a testament to the chamber-like imperatives of his latter-day music-making, not to mention the advantage of adequate rehearsal time! I should add that the finale’s hammer-blows are clearer and cleaner than I have ever heard them. Abbado does not include the third of these before the final coda but the hard, dry brutality of his clinching fortissimo is guaranteed to take you by surprise. Donald Mitchell provides excellent booklet-notes to cap a remarkable release that I would expect to find on next year’s Awards shortlist.

Symphony No 6

Coupled with Kindertotenlieder. Rückert-Lieder

Christa Ludwig mez BPO / Herbert von Karajan (DG)

Karajan’s classic Sixth confirmed his belated arrival as a major Mahler interpreter. His understanding of Mahler’s sound world – its links forward to Berg, Schoenberg and Webern as opposed to retrospective links with Wagner – is very acute.

Symphony No 6

LPO / Klaus Tennstedt (LPO)

Tennstedt exposes every nerve-ending of the piece from start to finish. Trenchancy is there with a vengeance from the word go – big-boned and punchy with snappy trombone accents. So it’s a corker, this performance. It sounds pretty good for 1983, though the BBC fashion then for a more ‘open’ sound slightly compromises the unflinching immediacy of the reading.

Read the original Gramophone review

Symphony No 7

Symphony No 7

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (DG)

Abbado’s account of Mahler’s Seventh was always a highlight of his cycle and remains the ideal choice for collectors requiring a central interpretation in modern sound. Steering a middle course between clear-sightedness and hysteria, and avoiding both the heavy, saturated textures of 19th-century Romanticism and the chilly rigidity of some of his own ‘modernist’ peers, he is, as the original review reported, ‘almost too respectable’. That said, it’s all to the good if the forthright theatricality and competitive instincts of the Chicago orchestra are held in check just a little. Even where Abbado underplays the drama of the moment, a sufficient sense of urgency is sustained by a combination of well-judged tempi, marvellously graduated dynamics and precisely balanced, ceaselessly changing textures. For those put off by Mahler’s supposed vulgarity, the unhurried classicism of Abbado’s reading may well be the most convincing demonstration of the music’s integrity. This is a piece Abbado continues to champion in concert with performances at the very highest level.

Symphony No 7

New York Philharmonic Orchestra / Leonard Bernstein (Sony Classical) Recorded 1965

We are often assured that great conductors of an earlier generation interpreted Mahler from within the Austrian tradition, encoding a sense of nostalgia, decay and incipient tragedy as distinct from the in-your-face calamities and neuroses proposed by Leonard Bernstein. Well, this is one Bernstein recording that should convince all but the most determined sceptics. It deserves a place in anyone’s collection now that it has been transferred to a single disc at mid-price. The white-hot communicative power is most obvious in the finale, which has never sounded more convincing than it does here; the only mildly questionable aspect of the reading is the second Nachtmusik, too languid for some. The transfer is satisfactory, albeit dimmer than one might have hoped. It sounds historic, but historic in more ways than one.

Symphony No 8

Symphony No 8

London Philharmonic Choir & Orchestra / Klaus Tennstedt (LPO)

The Royal Festival Hall was never a natural venue for Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, and I remember well how Klaus Tennstedt’s choirs spilled from the choir stalls into the adjoining side stalls and how boxes were deployed to accommodate the offstage brass and, at the highest point, Susan Bullock’s Mater Gloriosa. But what we lost in breadth and magnitude (the acoustic was much drier then) we gained in an all-enveloping and electrifying immediacy.

And so, with the biggest upbeat in music (and from days when the Festival Hall organ was complete!), Mahler’s hymnic invocation swept all before it. It was almost as if Tennstedt was striving to compensate for the constrictive sound of the hall by building the spatial perspective into his reading. Come the mighty development, he takes the text “Accende lumen sensibus” (“Inflame our senses with light”) at absolutely face value. As the fervour mounts to fever pitch – his sopranos Julia Varady and Jane Eaglen hurling out top Cs like they could be the last they ever sing – one almost doesn’t notice that the tempo is getting broader and broader. Tennstedt is one of the few conductors in my experience to almost convince me that impetus has nothing to do with speed. And, of course, though there is no ritardando marked in the momentous bars leading to the point of recapitulation, Tennstedt (who was nothing if not a traditionalist) is having none of it – the heavens duly open but in the certain knowledge that they will do so again, only bigger, with the Chorus Mysticus.

Part 2 begins with a poco adagio which, thanks to the kind of high-intensity string-playing only Tennstedt could elicit from the LPO, tugs at the emotional fabric of the music as few dared to do. To some it will feel overwrought, to most (or at least to staunch Mahlerians) it will be another instance of Tennstedt’s total identification with this music. His painting of the Faust scene is characteristically craggy, with the arrival of the Doctor’s heavenly escort prompting angelic high jinks far rougher and readier in tone than in some accounts. So, too, the casting of the male soloists, with Kenneth Riegel’s Doctor Marianus eschewing head voice for an often pained rendition of the cruelly high tessitura.

But as the Mater Gloriosa duly floats into view (the lovely Susan Bullock) and the force of love becomes unstoppable, Tennstedt is overwhelming. Try topping the orchestral peroration, offstage trumpets stretching the “Veni, Creator Spiritus” motif from the interval of a fifth beyond the octave to a heaven-storming ninth.

Symphony No 8

Heather Harper, Lucia Popp, Arleen Auger sops Yvonne Minton mez Helen Watts contr René Kollo ten John Shirley-Quirk bar Martti Talvela bass Vienna Boys’ Choir; Vienna State Opera Chorus; Vienna Singverein; Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Sir Georg Solti (Decca) Recorded 1971

Of the so-called classic accounts of the Eighth Symphony, it’s Solti’s which most conscientiously sets out to convey an impression of large forces in a big performance space, this despite the obvious resort to compression and other forms of gerrymandering. Whatever the inconsistencies of Decca’s multi-miking and overdubbing, the overall effect remains powerful even today. The remastering has not eradicated all trace of distortion at the very end and, given the impressive flood of choral tone at the start of the ‘Veni Creator Spiritus’, it still seems a shame that the soloists and the Chicago brass are quite so prominent in its closing stages. As for the performance itself, Solti’s extrovert way with Part 1 works tremendously without quite erasing memories of Bernstein’s ecstatic fervour. In Part 2, it may be the patient Wagnerian mysticism of Tennstedt that sticks in the mind. Less inclined to delay, Solti makes the material sound more operatic. Yet for its gut-wrenching theatricality and great solo singing, Solti’s version is up there with the best.

Symphony No 9

Symphony No 9

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan (DG) Recorded live 1982

Choice between the 1982 Karajan classic and the analogue studio recording is by no means easy. Both versions won Gramophone Awards in their day. This live performance remains a remarkable one, with a commitment to lucidity of sound and certainty of line. There’s nothing dispassionate about the way the Berlin Philharmonic tears into the Rondo-Burleske, the agogic touches of the analogue version ironed out without loss of intensity. True, Karajan doesn’t seek to emulate the passionate immediacy of a Barbirolli or a Bernstein but in his broadly conceived, gloriously played Adagio the sepulchral hush is as memorable as the eruptive climax. The finesse of the playing is unmatched.

Symphony No 9

Lucerne Festival Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (Accentus) Recorded live 2010

This, Claudio Abbado’s fourth commercial recording of the work, is even more luminous, elegant and subtly integrated than its predecessors. In some recent Abbado interpretations, the Mediterranean fluency and rapid pacing implies a hint of complacency or, at least, a reluctance to wrestle with those darker and more tumultuous corners of the score. But it certainly isn’t the case with this Ninth, which can only be described as unmissable.

The first movement, marked Andante comodo, now seems ideally plotted, more spacious than in his previous DVD recording with the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra (EuroArts), with playing even more proficient than in his famous Berlin concert version (DG). There is perhaps less gain in the inner movements, where sceptics (who tend to be American with this conductor) will levy the charge that Mahler executed with the refinement and subtlety of chamber music is Mahler deracinated or Mahler-lite. Perhaps so, yet it hardly seems to matter: Abbado’s almost playful approach brings its own rewards. The great final Adagio, crowning the reading even more effectively than before, is as deeply affecting as one has ever heard it.

An interpretation that might seem too cool is in fact superbly gauged to provide maximal catharsis by the close – and there are intrusive post-performance shots of weeping concert-goers thrown in to prove it. When the music finally ends and, as in any truly great account of this highly affecting score, one feels that life itself is ebbing away, all present are held in awed silence. Even when the time comes for Abbado finally to lower his hands and for the players to put down their instruments, the spell remains unbroken for a while longer. The ovation when it comes is suitably tremendous.

Symphony No 9

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Bruno Walter (Naxos or Dutton mono) Recorded live 1938

This is a historic document – the Ninth’s first commercial recording conducted by its dedicatee. Few modern performances offer more intensity in the first movement (Rattle and Bernstein perhaps excepted). Don’t be taken aback by the technical lapses of the VPO; this is music-making in which scrappiness and fervour are indissolubly linked.

Symphony No 10

Symphony No 10 (ed Cooke)

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (EMI / Warner Classics) Recorded live 1999

Over the years, Rattle has performed the work nearly 100 times, far more often than anyone else. Wooed by Berlin, he repeatedly offered them ‘Mahler ed Cooke’ and was repulsed. He made his Berlin conducting debut with the Sixth. But, after the announcement in June 1999 that he had won the orchestra’s vote in a head-to-head with Daniel Barenboim, he celebrated with two concert performances of the Tenth. A composite version is presented here. As always, Rattle obtains some devastatingly quiet string-playing, and technical standards are unprecedentedly high insofar as the revised performing version is concerned. Indeed, the danger that clinical precision will result in expressive coolness isn’t immediately dispelled by the self-confident meatiness of the violas at the start. We aren’t used to hearing the line immaculately tuned, with every accent clearly defined. The tempo is broader than before and, despite Rattle’s characteristic determination to articulate every detail, the mood is, at first, comparatively serene, even Olympian. Could Rattle be succumbing to the Karajan effect? But no – somehow he squares the circle. The neurotic trills, jabbing dissonances and tortuous counterpoint are relished as never before, within the context of a schizoid Adagio in which the Brucknerian string-writing is never undersold.

The conductor has not radically changed his approach to the rest of the work. As you might expect, the scherzos have greater security and verve. Their strange, hallucinatory choppiness is better served, although parts of the fourth movement remain perplexing despite the superb crispness and clarity of inner parts. More than ever, everything leads inexorably to the cathartic finale, brought off with a searing intensity that has you forgetting the relative baldness of the invention.

Berlin’s Philharmonie isn’t the easiest venue: with everything miked close, climaxes can turn oppressive but the results here are very credible and offer no grounds for hesitation. In short, this new version sweeps the board even more convincingly than his old (Bournemouth) one. Rattle makes the strongest case for an astonishing piece of revivification that only the most die-hard purists will resist.

Symphony No 10 (ed Cooke)

London Symphony Orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt (Testament mono)

Belying his low-key presentation, Cooke’s dramatic revelation, in his BBC talk on the Tenth Symphony, was that a continuous Mahlerian argument already existed on paper, needing only to be set free by a sympathetic editorial team. His own would take in the veteran émigré composer-conductor Berthold Goldschmidt and, subsequently, two budding composers, Colin and David Matthews. Alma, the composer’s widow, was apparently relying on the advice of Bruno Walter when she forbade further performances. Fortunately she was persuaded to think again, additional pages were found and the first public rendition of a full-length performing version took place in the Royal Albert Hall during the 1964 Proms season.

The necessarily incomplete studio rendering by the Philharmonia, including announcements as broadcast, moves more swiftly than the live account, preserving noises off and concluding applause. Both contain details later amended or corrected – which may or may not matter to you given the obvious fervour of the music-making. What it must have been to experience the -finale’s flute melody for the first time outside a BBC studio! Goldschmidt gives this exquisite moment all the time in the world.

It is a sad irony that Cooke, like Mahler himself, died young, leaving unfinished projects of his own, but he is well remembered here. The tapes, from whatever source, would appear to have been tactfully reprocessed to open out the mono sound and eliminate any awkward gaps in continuity. Strongly recommended.

Vocal Works

Das klagende Lied

Marina Shaguch sop Michelle DeYoung mez Thomas Moser ten Sergei Leiferkus bar San Francisco Symphony Chorus and Orchestra / Michael Tilson Thomas (SFS Media/Avie)

What a glorious prospect Mahler’s first major work opens up for us – and how beautifully it is realised here. The original three-part version of this ambitious folkloric cantata is like a musical manifesto of pretty well all Mahler to come. Horn-calls in the prelude to ‘Waldmärchen’ (‘Forest Tale’) awaken his unique nature-world; elfin woodwind fanfares intimate martial music as far as the Seventh and Eighth symphonies; the First Symphony (third movement) is germinating at the close of Part 1, the opening of the Second is already in place with the first bars of ‘Der Spielmann’ (‘The Wandering Musician’); and with ‘Hochzeitsstück’ (‘Wedding Feast’) Mahler seems to find himself in Act 2 of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung contemplating the opera he never wrote. But more startling than anything in Das klagende Lied is Mahler’s feeling for, and command of, the orchestra – and this from a composer who’d never heard a note of his own orchestration.

Recorded in 1996 (and originally released by RCA), the subtle detailing and nuancing of this performance indicates painstaking preparation but arrives in our living rooms sounding as if the ink is still wet on the page. Each repetition of that madrigal-like choral ritornello intensifies the lamentation of the title until release is found in the anguish of the wronged queen and soprano Marina Shaguch hurls out her leaping vocal line to bring down the walls of the castle. That’s Mahler’s innate theatricality for you. Quite a piece, and quite a performance.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf sop Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau bar London Symphony Orchestra / George Szell (EMI / Warner Classics)

EMI’s classic recording made in 1968 more or less puts all rivals out of court. Even those who find Schwarzkopf’s singing mannered will be hard pressed to find more persuasive versions of the female songs than she gives, while Fischer-Dieskau and Szell are in a class of their own most of the time. Bernstein’s CBS version, also from the late 1960s but with less spectacularly improved sound than EMI now provide, is also very fine, but for repeated listening Szell, conducting here with the kind of insight he showed on his famous Cleveland version of the Fourth Symphony, is the more controlled and keen-eared interpreter. Also, few command the musical stage as Fischer-Dieskau does in a song such as ‘Revelge’, where every drop of irony and revulsion from the spectre of war is fiercely, grimly caught.

Das Lied von der Erde

Christa Ludwig mez Fritz Wunderlich ten Philharmonia Orchestra, New Philharmonia Orchestra / Otto Klemperer (EMI / Warner Classics)

In a famous BBC TV interview Klemperer declared that he was the objective one, Walter the romantic, and he knew what he was talking about. Klemperer lays this music before you, even lays bare its soul by his simple method of steady tempi (too slow in the third song) and absolute textural clarity, but he doesn’t quite demand your emotional capitulation as does Walter (see below). Ludwig does that. In the tenor songs, Wunderlich can’t match Patzak, simply because of the older singer’s way with the text: ‘fest steh’n’ in the opening song, ‘Mir ist als wie im Traum’, the line plaintive and the tone poignant, are simply unsurpassable.

By any other yardstick, Wunderlich is a prized paragon, musical and vocally free. The sound on the revived EMI is very fresh: with voice and orchestra in perfect relationship and everything sharply defined, the old methods of the 1960s have nothing to fear here from today’s competition. These two old recordings will never be thrust aside; the Walter for its authority and intensity, the feeling of being present on a historic occasion, the Klemperer for its insistent strength and beautiful singing.

Das Lied von der Erde. Three Rückert-Lieder

Kathleen Ferrier contr Julius Patzak ten Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Bruno Walter (Decca)

The 1952 Walter will never lose its place at the heart of any review of Das Lied recordings. Walter obtains even richer, more impassioned, more pointed playing from the Vienna Philharmonic than in 1936 in, of course, improved sound. With his disciple Ferrier as alto soloist, her songs are richly, warmly voiced, and taken, particularly in the finale, to the limits of emotional involvement. Few have attempted to identify so completely with the work’s ethos of farewell and its thoughts of eternity. Ferrier envelops one to the core of one’s being. The wholly idiomatic and wonderfully expressive Patzak is the near-ideal tenor.

Rückert-Lieder. Kindertotenlieder. Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

Janet Baker; New Philharmonia Orchestra / Sir John Barbirolli (EMI / Warner Classics)

Tenderness, grace, impassioned directness, sublime Mahlerian inwardness: Janet Baker, in glorious voice, has them all, abetted by Barbirolli’s loving, yet never indulgent, accompaniments. Baker’s version of these songs is immensely moving.

Songs

Stephan Genz bar Roger Vignoles pf (Hyperion)

Stephan Genz's voice and style place him above his many noted contemporaries. His mellifluous baritone recalls that of a young Thomas Hampson, but his understanding of the Lieder genre is even more penetrating, as this Mahler recital reveals. Each song is shaped as a whole yet with subtleties of phrase and word-painting that seem inevitable in every respect, especially as the chosen tempi always seem the right ones.

Performing and listening to these songs with piano is inevitably a more intimate experience than when they are heard in their orchestral garb. The pair's rapport is evident throughout. Memorable are the the poise and stillness of 'Ich atmet' einen Linden duft' from the Rückert-Lieder, the eloquent sadness of 'Nicht Wiedersehen' and the restrained sorrow of the whole of Kindertotenlieder. Not a hint of sentimentality, such a danger in Mahler, spoils the experience of the composer's deeply felt emotions.

Hyperion's recording, beautifully balanced, catches the true quality of Genz's voice and the refinement of Vignoles's playing. This disc is an experience not to be missed by any lover of Mahler and/or of Lieder.

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/the-50-greatest-mahler-recordings