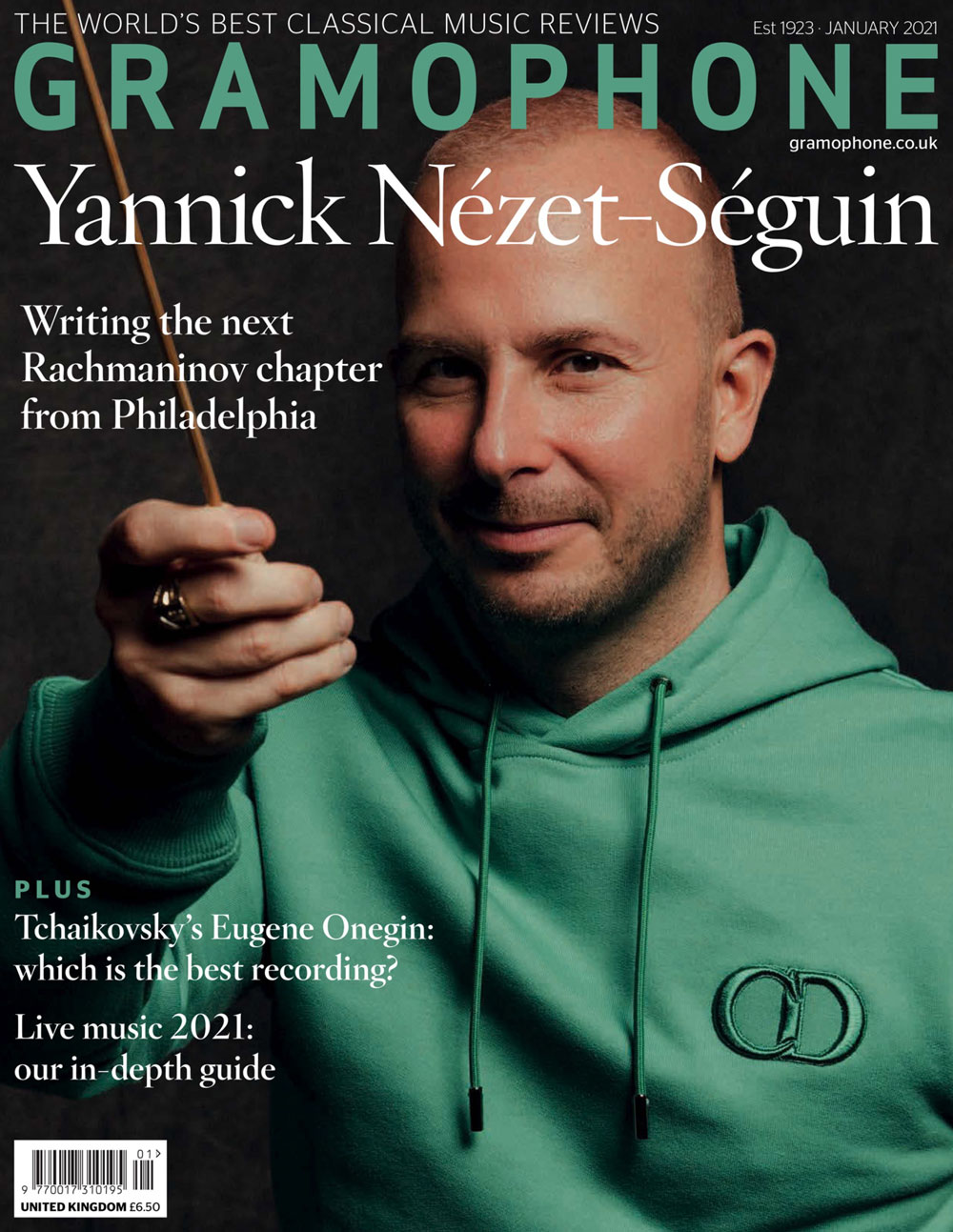

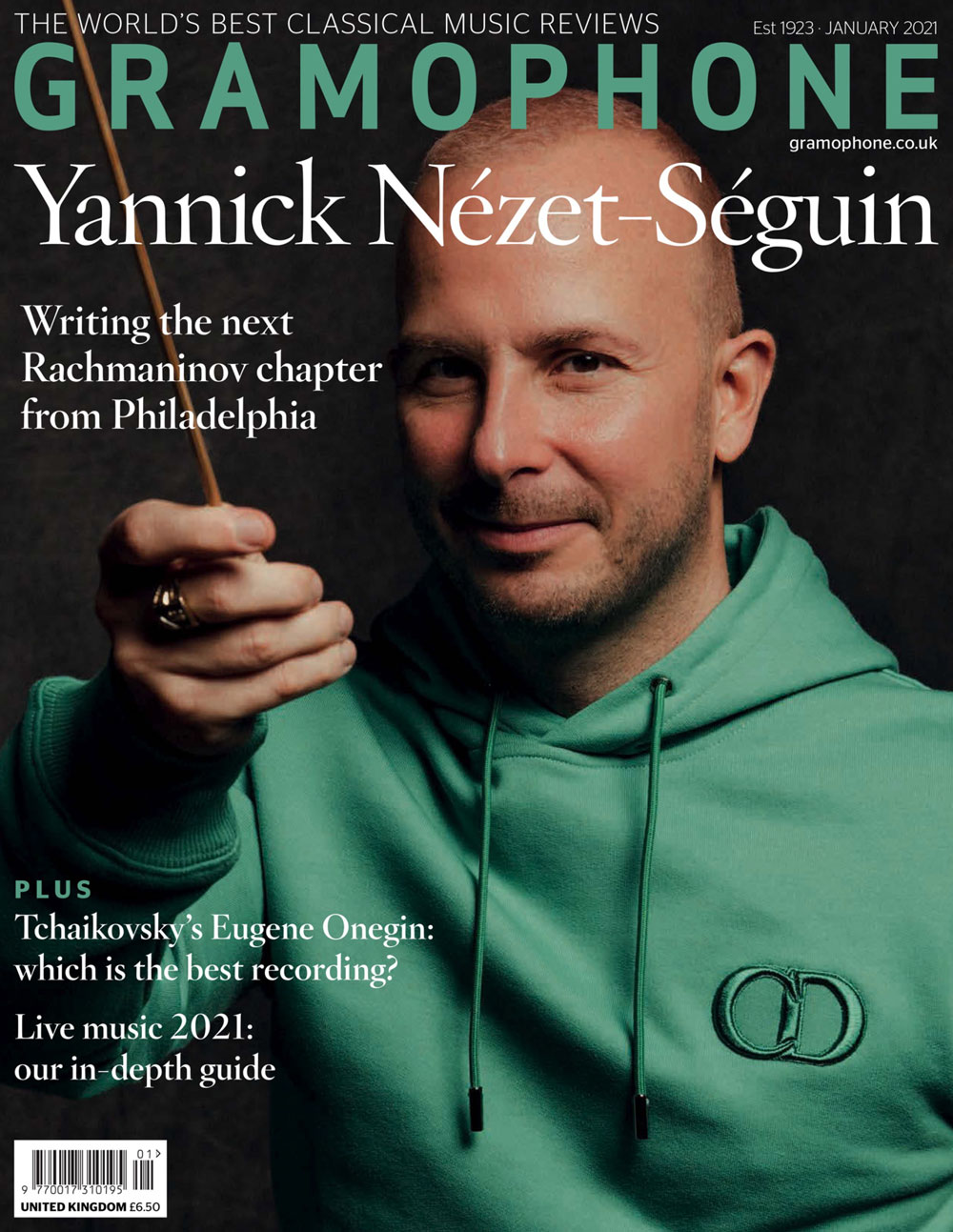

Orchestral

Piano Concertos Nos 1-5

Pierre-Laurent Aimard pf Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Teldec

The freshness of this set is remarkable. You do not have to listen far to be swept up by its spirit of renewal and discovery, and in Pierre-Laurent Aimard as soloist Nikolaus Harnoncourt has made an inspired choice. Theirs are not eccentric readings of these old warhorses – far from it. But they could be called idiosyncratic – from Harnoncourt would you have expected anything less? – and to the extent that the set gives a shock to received ideas it is challenging. It does not seek to banish all conventional wisdom about the pieces, but it has asked a lot of questions about them, as interpreters should, and I warm to it not only for the boldness of its answers but for finding so many of the right questions to ask.

These are modern performances which have acquired richness and some of their focus from curiosity about playing styles and sound production of the past. What can be deduced about the likely nature of mass, weight and orchestral perspectives and how the musical language was spoken from what is known of instruments and performance practices in Beethoven’s time? Harnoncourt offers some answers that will be familiar to admirers of his Teldec recording of the symphonies (11/91). He favours leaner string textures than the norm and gets his players in the excellent Chamber Orchestra of Europe to command a wide range of expressive weight and accent; this they do with an immediacy of effect that is striking. Yet there is a satisfying body to the string sound, too. From all the orchestral sections the playing is of the highest class – the woodwind and brass often pungent, the thwack of the timpani leathery and distinctive in tutti passages (and the player of them relishing the big solo moment after the cadenza in the first movement of the Concerto No 3 in C minor). The performances gain an edge from all this which has nothing to do with a ‘period’ stance but everything to do with what I take to be Harnoncourt’s objectives: to regain the freshness and force of what was once new, to recover the qualities of exhilaration and disturbance that these works possess ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

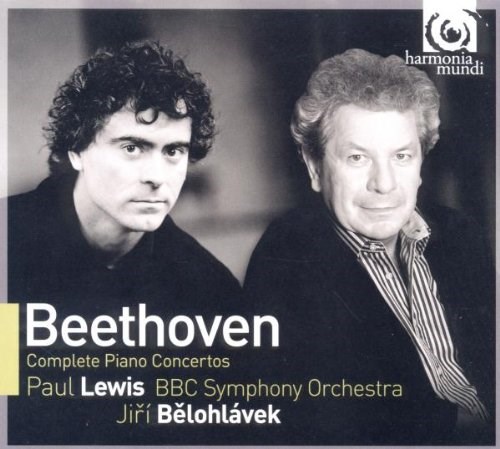

Piano Concertos Nos 1-5

Paul Lewis pf BBC Symphony Orchestra / Jiří Bělohlávek

Harmonia Mundi

With this three-disc album of Beethoven’s piano concertos Paul Lewis complements his earlier set of the 32 sonatas and also his appearances at the Proms this summer where for the first time all five concertos will be played by a single artist. So may I say at once that Harmonia Mundi’s eagerly awaited set is a superlative achievement and that Lewis’s partnership with Jirí Belohlávek is an ideal match of musical feeling, vigour and refinement.

True, for aficionados of eccentricity – even of brilliant eccentricity – from the likes of Gould, Pletnev and Mustonen, Lewis may at times seem overly restrained but the rewards of such civilised, musically responsible and vital playing seem to me infinite. Above all there is no sense of an artist looking over his shoulder to see what other pianists have come up with. Throughout the cycle Lewis is enviably and naturally true to his own distinctive lights, his unassuming but shining musicianship always paramount. His stylistic consistency can make the singling-out of this or that detail irrelevant, yet how could I fail to mention Lewis’s and Belohlávek’s true sense of the Allegro con brio in the First Concerto, in music-making that is vital but never driven? Less rugged than, say, Serkin, such playing is no less personal and committed. In the central Largo Lewis achieves a quiet, hauntingly sustained poise and eloquence, while in the finale his crisp articulation sends Beethoven’s early ebullience dancing into captivating life ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

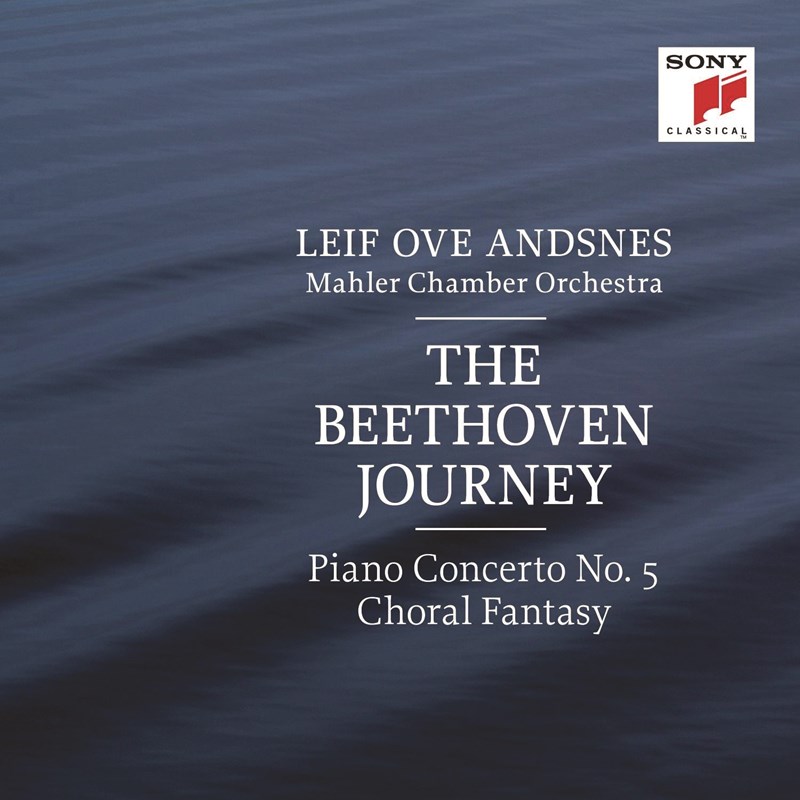

'The Beethoven Journey' (Piano Concertos Nos 1-5. Choral Fantasia)

Mahler Chamber Orchestra / Leif Ove Andsnes pf

Sony

Review of Vol 3: To have arrived so soon at the end of this journey seems almost a pity, for the company has been most engaging, by turns profound and delightful. It’s a rare treat to have the Choral Fantasy as a juicy extra to the concertos. I was made more than usually aware of its original context – as the finale of the famously epic concert that also saw the premieres of, among others, the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and the Fourth Concerto; suddenly I noticed connections between the Fantasy and the Fourth that previously passed me by. Robert Levin may be matchless in conveying the rhetoric of the extended piano opening but Andsnes manages to be lithe and spontaneous-sounding, and doesn’t overplay hints of melodrama – dangerously tempting with all those diminished sevenths scattered about. The Mahler CO wind are predictably characterful in their variations on the theme that prefigures the ‘Ode to Joy’ and the chorus are fervent without sounding too butch. That’s in part down to the performers and in part surely the recording, in that most eloquent of spaces, the Prague Rudolfinum.

The Fantasy is much more than just a handy filler but it’s the Fifth Concerto that is likely to be the real draw. So how does this one stack up? Andsnes makes his mark in the initial flourish with playing that has the requisite steel but which is tempered with a twinkle. The qualities that made the previous instalments so compelling are here too: the naturalness with which piano and orchestra meld and converse and, at times, tussle; the airiness of the textures; the subtlety of the details. The clarinet phrases (at 1'21"), for instance, dance more than those of Rattle’s BPO. And the Mahler CO’s timpanist adds to the buoyancy of effect but again subtlety is the watchword. In a way Andsnes reminds me of Schnabel in his sureness of touch, albeit in a very different style; Kissin’s point-making and self-conscious massiveness have no place here ...

Read the full reviews in the Reviews Database: Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3

☆

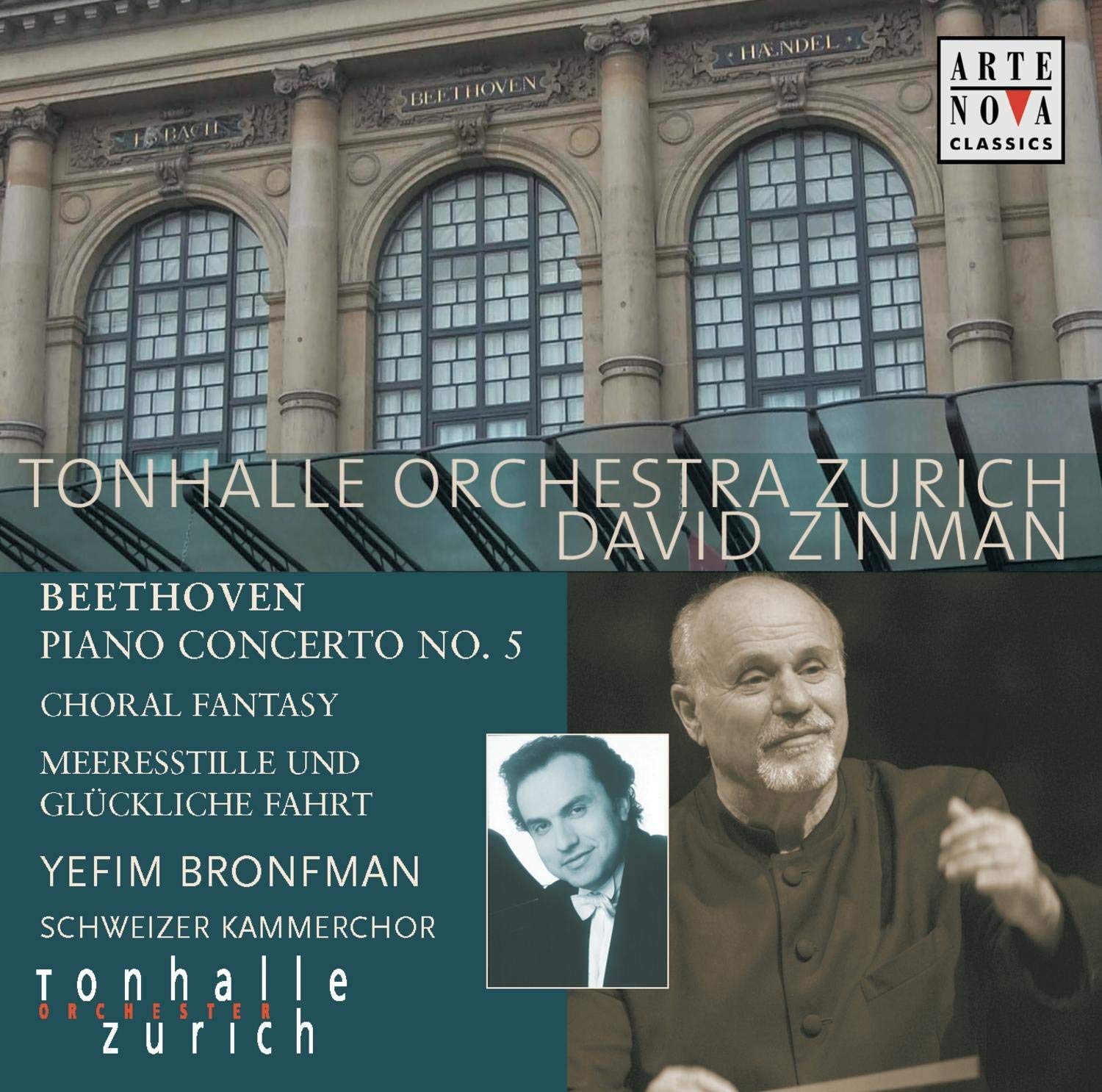

Piano Concertos Nos 1-5. Choral Fantasia. Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage

Yefim Bronfman pf Tonhalle Orchestra, Zurich / David Zinman

Brilliant Classics (originally Arte Nova)

This Zurich performance of the First Concerto is beautifully articulated. True, there are moments of grandeur but the overall impression is of a poised, at times chamber-like traversal, with sculpted pianism and crisply pointed orchestral support. The sensation of shared listening, between Bronfman and the players and between the players themselves, is at its most acute in the First Concerto’s Largo, which although kept on a fairly tight rein is extremely supple (the woodwinds in particular excel). In the finale, Bronfman and the Tonhalle provide a clear, shapely aural picture.

Bronfman’s B flat Concerto (No 2) has the expected composure, the many running passages in the first movement polished if relatively understated. Again the slow movement is full of unaffected poetry and the finale (with the odd added embellishment) is appropriately buoyant – has Bronfman ever played better? ...

Read the full reviews in the Reviews Database: Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 3 & 4

Maria João Pires pf Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra / Daniel Harding

DG

Even with a never-ending stream of Beethoven piano concerto recordings, whether from established masters (Kempff, Arrau, Gilels, etc) or work in progress (Andsnes and Sudbin), few performances come within distance of Pires’s Classical/Romantic perspective. In her own memorable ‘artist’s note’ she speaks of that knife-edge poise between creator and recreator, of what must finally be resolved into a ‘primal simplicity’. And here you sense that she is among those truly great artists who, in Charles Rosen’s words, appear to do so little and end by doing everything (his focus on Lipatti, Clara Haskil and Solomon).

Not since Myra Hess have I heard a more rapt sense of the Fourth Concerto’s ineffable poetry, whether in the unfaltering poise of her opening, her radiant, dancing Vivace finale or, perhaps most of all, in the Andante’s nodal and expressive centre, where she achieves wonders of eloquence and transparency. Never for a moment does she over-reach herself or force her pace and sonority. Others such as Arrau may speak with a weightier voice but even that great pianist would surely have marvelled at the purity and sheen of Pires’s playing. Few pianists have ever been more true to their own lights and it is hardly surprising that her many performances of this concerto in London and elsewhere have become the stuff of legends ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 1-5

Murray Perahia pf Concertgebouw Orchestra / Bernard Haitink

Sony Classical

Seasoned collectors will readily warm to the beautifully recorded piano even if the brass section is placed rather distantly in the empty concert hall ambience. That said, a wealth of often obscured orchestral detail emerges without any feeling of being artificially lit (the woodwind exchanges in the opening movements of the First and Second concertos, for example). There is something reassuring about the readings of all five concertos. The perfect civility of Perahia’s playing is a joy, the deeply felt slow movements particularly rewarding (try that of the Fourth, following the choice of the longer of the two cadenzas for the first movement) ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 2 & 5

Martin Helmchen pf Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin / Andrew Manze

Alpha

Vital energy and connoisseur-level sensitivity to original turns of phrase reign supreme in Helmchen’s reading of the Mozart-influenced Second Concerto, and he appropriately exchanges its skittish garments for a serious black frock-coat with the first-movement cadenza, composed much later than the surrounding music, layering the soundscape in something that could have come right out of the Hammerklavier Sonata. The lonely piano recitative of the slow movement is a heart-melting moment. Comparison with Helmchen’s own recording of this concerto from the final round of the 2001 Clara Haskil competition (which he won) is the best proof of how much a close affinity between pianist and conductor matters. Not only has Helmchen matured in his pianism but he is given wings by an orchestra that shares intimate moments with the piano at one point and twirls with it at the next. The finale is a joyous pas de deux, and how charming is Helmchen’s invitation to the dance when he adds a subtle agogic accent to the very opening of the movement. This is another account to be placed alongside the finest, including Argerich, and for me surpassing Glenn Gould/Bernstein ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Piano Concertos Nos 4 & 5

Emil Gilels pf Philharmonia Orchestra / Leopold Ludwig

Warner Classics

This is one of the – perhaps the most – perfect accounts of the Fourth Concerto ever recorded. Poetry and virtuosity are held in perfect poise, with Ludwig and the Philharmonia providing a near-ideal accompaniment. The recording is also very fine, though be sure to gauge the levels correctly by first sampling one of the tuttis. If the volume is set too high at the start, you will miss the stealing magic of Gilels’s and the orchestra’s initial entries and you will be further discomfited by tape hiss that, with the disc played at a properly judged level, is more or less inaudible ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Violin Concerto

Itzhak Perlman vn Philharmonia Orchestra / Carlo Maria Giulini

Warner Classics

Perlman's first entry couId hardly be more deceptive, that ladder-like climb of spread octaves which many virtuosi (Anne-Sophie Mutter on DG for example) present commandingly, but which Perlman plays with such gentleness that he emerges almost imperceptibly from the orchestra. It is a measure of Perlman's artistry that an effect which could sound selfconsciously poetic or even weak at once establishes the soloist's command; for this is a spacious performance which uses a relatively measured tempo, steadily maintained, to create the strongest possible structure in a movement which in time at least (almost 25 minutes) is Beethoven's longest symphonic first movement. Where both Chung (Decca) and Mutter are above all lyrical and meditative, illuminatingly so, Perlman's is a more obviously virile purposeful reading with the orchestral tuttis closely co-ordinated - just as they are in the Krebbers version (Philips) with a soloist who at the time was also concertmaster of the orchestra. One might even relate the reading of that first movement to Giulini's spacious but concentrated reading of the Eroica Symphony with the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra (DG, 5/79). It is striking that even in the Kreisler cadenza Perlman prefers to keep the feeling of a steady pulse, and the entry into the coda in its total purity and simplicity is even more affecting than the fine accounts in the other three versions.

Both there and in the slow movement Mutter and Chung adopt a more consciously expressive style, but there is no question at any point of Perlman sounding rigid, for within his steady pulse he 'magicks' phrase after phrase. The hushed third theme of the slow movement has an easeful serenity to set against the more tender, vulnerable emotions conveyed by Chung and Mutter. With them poetry is perhaps more important than drama, but Perlman - certainly poetic in his way, always noting the many key passages marked dolce - confirms the strength of his reading in his superbly sprung account of the finale, the tempo marginally faster than that of any of the others (markedly faster than Chung) but masterfully confident. With full, warm digital recording, there is no finer version available, combining as it does so many of the special qualities one finds in the Chung and Mutter versions on the one hand, and in the strong, incisive Krebbers on the other. Edward Greenfield (September 1981)

☆

Violin Concerto

Isabelle Faust vn Orchestra Mozart / Claudio Abbado

Harmonia Mundi

Beethoven may not give as many directions as Berg, but from the very first bars the Orchestra Mozart’s woodwind choir show the same care over detail, the instruments perfectly balanced and with a commitment to bringing out the music’s soulful, expressive character. This sets the tone for the performance, Abbado encouraging his players to maximise the expressive quality of each theme, while keeping a firm hand on the unfolding of the larger design.

He and Faust see eye to eye in wishing to preserve a proper Allegro ma non troppo for the first movement and not to be awed by the work’s reputation into presenting it as a grand, Olympian utterance with little vitality (as on the Maxim Vengerov/Rostropovich recording). It’s not just a matter of tempo, either; to all the running passages in the first movement and finale, Isabelle Faust brings a spirited style that at moments becomes positively fiery. A notable example is her cadenza in the finale (track 5, 6'20"). Faust bases her cadenzas and lead-ins on those Beethoven wrote for his adaptation of the work as a piano concerto. This is often an uncomfortable option: Beethoven’s cadenzas (that in the first movement includes an important role for timpani) take the music in surprising directions – more extrovert and playful – and it’s quite difficult to arrange some passages idiomatically for the violin. However, by judicious omission, brilliant playing and sheer conviction, Faust finds a solution that’s both authentically Beethovenian and violinistically convincing ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Violin Concerto

Christian Tetzlaff vn Deutsches SymphonieOrchester Berlin / Robin Ticciati

Ondine

The first movement’s serene central section (played in tempo) allows for a welcome spot of repose and elsewhere Tetzlaff’s sweet, delicately spun tone contrasts with, or should I say complements, Ticciati’s assertive, occasionally bullish accompaniment. The Larghetto is beautifully done, its effect underlined through the sheer energy and character of the outer movements. There’s never any doubt that what you’re listening to is a real concerto, a battle of wills, more in line with Zehetmair and Brüggen (who use Wolfgang Schneiderhan’s cadenza with timpani) or Kremer and Harnoncourt (a cadenza incorporating piano) than with the likes of Perlman, Zukerman or Kennedy. Who knows: maybe this is roughly what Beethoven originally had in mind? It’s possible, even probable. One thing’s for sure: never before has this indelible masterpiece sounded more like a profound precursor of Paganini...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Violin Concerto

Jascha Heifetz vn NBC Symphony Orchestra / Arturo Toscanini

Naxos

‘An old diamond in the rough’ is how Robert C Marsh (Toscanini and the Art of Orchestra Performance; London: 1956) recalled the original Victor 78s of this 1940 Heifetz Studio 8-H recording of the Beethoven. Of the LP reissue he wrote: ‘On the whole, the recording is so dead and artificial that at times the thin line of violin sound reminds one of something from the golden age of Thomas Edison’s tinfoil cylinder rather than 1940.’ Early CD transfers suggested that all was not lost but even they barely anticipated the extraordinary fineness of the sound we now have on this transfer by archivist and restorer Mark Obert-Thorn.

The performance itself is one of the most remarkable the gramophone has ever given us. The visionary, high tessitura violin writing is realised by Heifetz with a technical surety which is indistinguishable, in the final analysis, from his sense of the work as one of Beethoven’s most sublime explorations of that world (in Schiller’s phrase) ‘above the stars where He must dwell’. Those who would query the ‘depth’ of Heifetz’s reading miss this point entirely. To adapt Oscar Wilde, it is they who are in the gutter, Heifetz who is looking at the stars ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Triple Concerto

David Oistrakh vn Mstislav Rostropovich vc Sviatoslav Richter pf Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

Warner Classics

These are illustrious performances and make a splendid coupling at mid-price. EMI planned for a long time to assemble this starry line-up of soloists, conductor and orchestra for Beethoven's Triple Concerto, and the artists do not disappoint, bringing sweetness as well as strength to a work which in lesser hands can sound clumsy and long-winded. The recording, made in a Berlin church in 1969, is warm, spacious and well balanced, placing the soloists in a gentle spotlight. Indeed, the sound need make no apology for its age, and since we also hear playing of effortless mastery this disc would be worth the money for this work alone. Christopher Headington (July 1993)

☆

Symphonies Nos 1-9

Chamber Orchestra of Europe / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Warner Classics

Stravinsky called Beethoven's Grosse Fuge ''that absolutely contemporary work that will be contemporary for ever''. Looking over what has happened in Beethoven performance in the concert-hall and on record over the last two or three years I've had the growing feeling that the same is true of the symphonies. Just when everybody seemed to be saying that the mighty nine had been worked to death, along came Christopher Hogwood, Frans Bruggen and that provocateur par excellence Roger Norrington to shake us out of our complacency. Then, last month, came confirmation in Gunter Wand's Eroica that the traditional-classical approach can still be roundly satisfying.

And now this – a new Beethoven cycle which manages to combine the shock of the new with an uncanny sense of familiarity. Harnoncourt doesn't pretend that what he offers is Beethoven as the composer imagined it. With the exception of the trumpets, the instruments are all modern, and while phrasing, rhythmic articulation, expression and balance reveal Harnoncourt's rigorous and passionate pursuit of historical truth, the results neither sound nor feel like anything offered under that banner before. Right from the start—the slow introduction to the First Symphony – the feeling that emerges through the finely differentiated phrasing is surprising in its intensity ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphonies Nos 1-9

Gewandhausorchester, Leipzig / Riccardo Chailly

Decca

The fact that the classic impulse vies with the Romantic throughout Beethoven’s nine symphonies presents a perennial problem to would-be interpreters. Klemperer came as close as any conductor to enabling both impulses to inhabit a single style. Elsewhere Romantics vie with the Classicists, while the temporisers, sailing under various flags of convenience, attempt assorted syntheses of their own. Riccardo Chailly’s first recorded Beethoven cycle shows him to be a Classicist through and through. This is no surprise given the classicising tendency of the Toscanini-led Italian school of Beethoven performance. There are classicising tendencies in Leipzig too. It was Mendelssohn who set the Gewandhaus Beethoven agenda in the 1840s, aspects of which have never entirely disappeared. When Kurt Masur recorded the symphonies in the 1970s, Robert Layton wrote in these columns of an orchestra that was consistently sensitive in its responses, its expression unforced, the overall sonority beautifully weighted and eminently cultured.

You can hear music-making of comparable pedigree at the start of the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony. Chailly’s tempo is swift. But just as Toscanini’s marginally slower tempo never loses a sense of forward impulse, so Chailly’s never seems hurried. There is also a lovely Italianate cantabile which period strings would find it impossible (and possibly undesirable) to match, and which you will look for in vain in Simon Rattle’s Vienna Philharmonic account, where the orchestra suffers the double burden of an inordinately slow tempo and the imposition of an astringent “period” sonority on its own natural sound. Under Chailly the Leipzig players never sound less than their eloquent selves ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphonies Nos 1-9

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Mariss Jansons

BR-Klassik

This is an exceptional realisation of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, one of those rare occasions when one is left with a feeling of having been in the presence of the thing itself. The key to the cycle’s success is the quality of the musicianship. Thanks to Mariss Jansons’s expert schooling of his superb Bavarian musicians in works which continue to enthral, move and entertain him, the dramatic and expressive elements are derived from within rather than – as is often the case with lesser conductors – imposed from without.

The project comes to us in two distinct forms. The ArtHaus DVDs give us the nine symphonies luminously and unfussily filmed live in Tokyo’s Suntory Hall. By contrast, Bavarian Radio’s six-CD set intermingles the symphonies (also mainly recorded live in Tokyo) with six newly commissioned ‘reflections’ on them by living composers.

From the information provided by ArtHaus it’s impossible to say to what extent the different versions overlap. The Tokyo performances on CD and DVD are self-evidently from the same cycle, though not I suspect from the same performances. To complicate matters further, two performances on the CD set – the Eroica and the Pastoral – were recorded live in Munich’s Herkulessaal shortly before the Japanese tour. Not that the Tokyo performances of the Eroica and Pastoral we have on DVD are necessarily inferior. (I marginally prefer them. They are a touch broader yet, paradoxically, a degree or two tauter.) ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphonies Nos 1-9

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

DG

The exceptional quality, both musical and technical, of this, the first set of the nine in the history of the gramophone to be released as a single cycle, took the symphonies to audiences old and new across the globe; and did so in well-assimilated readings that refuse to date.

☆

Symphonies Nos 2 & 8

London Classical Players / Sir Roger Norrington

Erato

With this exceptionally exciting new record, Roger Norrington joins Frans Bruggen and John Eliot Gardiner among a small elite of musicians working with period instruments whose interpretations of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven can stand comparison with the best we have had on record on modern instruments during the past 20 or 30 years.

The works Norrington has selected to launch this projected Beethoven cycle are, it must be said, shrewdly chosen. They suit Norrington's temperament and musicological preoccupations unusually well. The D major Symphony is a joy from start to finish, whilst Norrington treats the F major as though it was specially written for him in an electrifying performance which challenges such distinguished versions as the 1952 NBC SO/Toscanini and the 1963 Karajan set made for DG in Berlin.

Like his revered seniors, Norrington has learnt conducting in the opera house. Though he conducts Beethoven's music with the verve of a young man who has just discovered it for the first time, he is in years (53 this month) an experienced musician with the kind of control over rhythm and argument which was always the hallmark of the very best kind of operatically trained musicians. Norrington's way with Beethoven – which is recognizably Toscaninian in some of its aspects - is mapped out in his own sleeve-note where he states as his aim the recapturing of much of "the exhilaration and sheer disturbance that his music certainly generated in his day". Like Toscanini, Erich Kleiber, and others before him, Norrington achieves this not by the imposition on the music of some world view but by taking up its immediate intellectual and physical challenges.

Norrington is not unduly preoccupied by matters of orchestral size (44 players are listed on the sleeve) or by pitch (the London Classical Players have settled for A = 430). Sound interests him a good deal. Throughout these two performances the contributions of horns, trumpets and drums most rivet the attention (the introduction to the Second Symphony's first movement is glorious); by contrast, the woodwinds have, to modern ears, an almost rustic charm, a naif quality which technology and sophisticated playing techniques have to some extent obliterated. What really fascinates Norrington, though, is rhythm and pulse and their determining agencies: 18th-century performing styles, instrumental articulacy (most notably, bowing methods), and Beethoven's own metronome markings.

In his sleeve-note annotations, Norrington is somewhat cavalier on the metronome question. Beethoven's metronome marks are printed alongside the movement titles but having set this particular hare running, Norrington declines to explain why some of his tempos fall short of those advertised. In fact, the metronomes are good in the Second Symphony, the Larghetto apart, and in the middle movements of the Eighth, but not in the Eighth's quick outer movements. That said, Norrington strives to get as near to the metronome as is humanly possible consistent with instrumental clarity. He plays the first movement of the Eighth at nearly 60 bars to the minute (the metronome is 69) which is quicker than Toscanini or Karajan; and he takes the finale at arround 74 (the metronome is 84). However, Karajan's 1962 Berlin performance (from the DG set already mentioned) is even quicker and superior in articulation, Norrington plays the Eighth Symphony's third movement as a quick dance and makes excellent sense of crotchet = 126, a marking often regarded as being beyond the pale. The second movement is spot on: as witty and exact a reading as you are likely to hear.

It must be said that at these tempos Norrington stresses the anxious, obsessive side of Beethoven's artistic make-up. I can well imagine Sir Thomas Beecham opining from some celestial vantage point that the music was quite as vital and rather wittier at his rather more considered tempos; but in Beethoven urbanity is not everything. In the Second Symphony Norrington does make the music smile and dance without any significant loss of forward momentum, and he treats the metronome marks more consistently than Toscanini (who rushed the Scherzo) or Karajan (who spins out the symphony's introduction), whilst sharing with them a belief in a really forward-moving pulse in the Larghetto (again an approach to the printed metronome if not the thing itself). On his rival L'Oiseau-Lyre disc (3/86), also played with period instruments, Hogwood broadens the slow introduction in the Karajan manner. More seriously, he lacks real control of his band. The sound he draws from his players is turgid and unwieldy and his readings seem random and cavalier alongside Norrington's astutely judged readings.

The recordings are warm and vivid and generally well balanced. The fff climax of the development of the Eighth Symphony's first movement is slightly underpowered, which is odd when the horns and trumpets are elsewhere so thrillingly caught; perhaps, in the Eighth, the recording could have been a shade tighter and drier in order better to define the playing of the London Classical Players. None the less, this is the most interesting and enjoyable new record of a Beethoven symphony I have heard for some considerable time. Richard Osborne (March, 1987)

☆

Symphony No 3. Overtures – Leonore Nos 1 & 2

Philharmonia Orchestra / Otto Klemperer

Warner Classics

This is a great performance, steady yet purposeful, with textures that seem hewn out of granite. (Once or twice they cause a slight buzz of distortion for which EMI apologise in their booklet.) There is no exposition repeat, and the trumpets blaze out illicitly in the first movement coda, but this is still one of the great Eroicas on record. As Karajan announced to Klemperer after flying in to a concert performance around this time: 'I have come only to thank you, and say that I hope I shall live to conduct the Funeral March as well as you have done'. Richard Osborne (April, 1992)

☆

Symphonies Nos 4 and 5

Minnesota Orchestra / Osmo Vänskä

BIS

It was during Osmo Vänskä’s time with the BBC Scottish SO that his Beethoven began winning golden opinions. There was an admired recording of the Pastoral Symphony, given away with a magazine, and a Proms performance of the Seventh Symphony which David Gutman described as ‘terrifically fresh and alert’ (BBC Proms, 11/99). Vänkä’s new recording of the Fourth Symphony is that, and more. His account of the Fifth also bristles with character.

Where the Fourth is concerned, I confess to a bias in favour of readings which match Apollonian loveliness with Dionysiac drive. Toscanini blazed the trail with his glorious 1939 BBC SO recording; Karajan followed in 1962 with a Berlin performance of unimaginable grace and fire; and Rattle was not far behind with his 2002 Vienna Philharmonic account. Vänskä’s reading is comparable to these: fiery but not relentless. Metronome marks are important but not mandatory. Transparent textures and a rigorous way with dynamics also feature. Of particular interest is the skill with which Vänskä keeps the bass line, and thus the music’s harmonic contour, continuously in view, never easy to do given the ‘open’ nature of Beethoven’s scoring ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

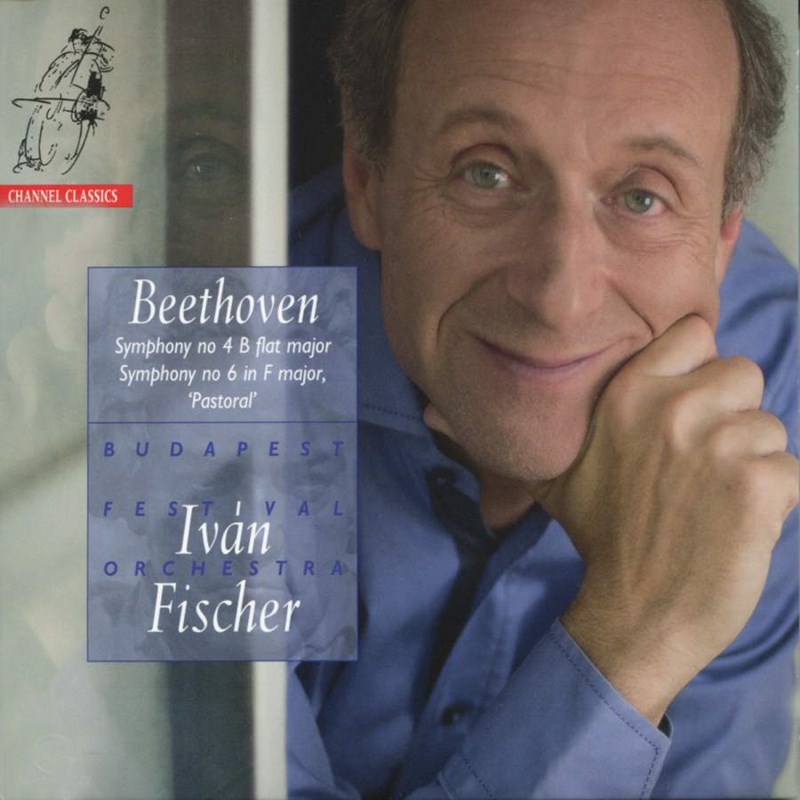

Symphonies Nos 4 & 6

Budapest Festival Orchestra / Iván Fischer

Channel Classics

It comes as no surprise to find these marvellous Budapest musicians moving the Pastoral Symphony downstream along the Danube from the woods by Heiligenstadt to the countryside beyond Buda. The specifically “east of Vienna” dimension is not merely felt in the fierier thrust of the 2/4 section of the “Peasant’s Merrymaking”. It is all-pervasive.

Iván Fischer’s direction is in the Toscanini class in its clarity and verve. Not that his tempi are at all Toscanini-like. The second and last movements have a Furtwänglerlike breadth, though such is Fischer’s mastery of ease within motion and motion within repose, there is nothing here that is long-drawn. Like Karl Böhm’s celebrated VPO Pastoral, this is also a closely observed reading, richly “characteristic”.

Furtwängler spoke of “a quality of absorption in the Pastoral which is related to the religious sphere”. The finale’s heading, “Beneficent feelings bound with thanks to the Godhead”, confirms the concept but it is rare nowadays to hear it realised. Daringly, Fischer has the horn-call which ushers in the finale met for the first eight bars by a solo violin as the shepherds’ hymn steals in upon the air. The effect is not unlike the entry of the solo violin in the Benedictus of the Missa solemnis. Aptly so, since it ushers in a reading of the finale which is unashamedly devout.

Fischer’s approach to the Pastoral is quite different from his approach to the Fourth. The resemblance here to Karajan’s 1962 Berlin recording is uncanny, doubly so given the quality of playing and direction needed to bring off a reading of such pace, poise and beauty. Not even Karajan attempted to re-enact the miracle. Which is not to say that the Budapest performance is a carbon copy of the Karajan. Fischer is quicker in the slow movement where he retains that mm=72 pulse which can plausibly inform all four movements. In fact, he presses on beyond that all-informing pulse in the finale. Not that the racy tempo affects the feel of a performance which has zest and humour, and which, like the Karajan, realises to perfection Beethoven’s seemingly effortless marriage of the spirits of Apollo and Dionysus. Richard Osborne (January 2011)

☆

Symphonies Nos 5 & 7

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Carlos Kleiber

DG

It is interesting to reflect that in 1974 there was not a single entry under the name 'Kleiber, Carlos' in The Gramophone Classical Record Catalogue. 'Kleiber, Erich': certainly. Among other things, he had recorded a famous Beethoven Fifth in 1953 (Decca, 9/87). I still remember the sinking feeling I experienced – a mere tiro reviewer on Gramophone – when I dropped into the post-box my 1000-word rave review (they had asked for 200) of what struck me as being one of the most articulate and incandescent Beethoven Fifths I had ever heard.

In Germany, they would probably have spiked the review. There is, after all, more than a hint of triplet-rhythm in Carlos Kleiber's conducting of the opening motto, a point – eagerly seized on by some German reviewers – which I had omitted to mention in my 1000-word encomium.

The performance doesn't stale, though it is the first movement that stays most vividly in the memory. I had forgotten, for instance, how steady – Klemperer-like, almost – the Scherzo and finale are. (Early Klemperer, that is: the Klemperer of the famous 1956 Philharmonia Fifth or his even earlier Vox recording – 5/93) ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphonies Nos 5 & 7

New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra / Arturo Toscanini

Naxos

I don’t know who to pity more: the budding maestro who hears this Beethoven Fifth before attempting to conduct the work himself‚ or the one who doesn’t. Either way‚ Toscanini is a near-impossible act to follow. But then in a sense he was fortunate. He didn’t have a fat record catalogue full of Rostrum Greats to live up to and he wasn’t under pressure to say something new‚ or at least something different. On the contrary‚ Toscanini’s avowed mission was to clean up where others had indulged in interpretative excess. And he could as well have been cleaning up for the future. In November I was humming and hawing over Sir Simon Rattle’s fascinating but fussy Fifth with the VPO (EMI). Had this new Naxos release been to hand‚ I might have focused Rattle’s calculated individuality in relation to Toscanini’s directness and elasticity. There are numerous Toscanini Fifths in public or private circulation‚ at least four of them dating from the 1930s. This one is lithe‚ dynamic and consistently commanding. It was in fact RCA Victor’s second Toscanini Fifth‚ tauter and tidier than its better-recorded live 1931 predecessor‚ though like the earlier version it was never actually passed for commercial release. Comparing it with Toscanini’s wellknown 1952 NBC recording finds numberless instances where a natural easing of pace helps underline essential transitions‚ such as the quiet alternation of winds and strings that holds the tension at the centre of the first movement ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphonies Nos 5 & 7

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique / John Eliot Gardiner

SDG

So palpable is the excitement of these live performances that it almost comes as a shock that the applause has been excised. I was out of my seat at the end of the Seventh and I can only assume that a patch was made of the final pages, because no audience could conceivably have contained itself. From the very start, the cut-to-the-bone immediacy of the sound puts you up close and personal to the performance, lending a granite strength to the crunch of those chords and the rosiny resilience of those striding string scales. The dancing flute theme is really up-tempo and the blare of natural horns at the tutti brings an earthiness, a rawness, to the proceedings. The dance starts here, the ‘apotheosis’ comes later.

John Eliot Gardiner and his resplendent Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique rejoice here in the sheer physicality of the music, the bounding rhythms, the stomping accents. There’s an implicit delirium in this music that would culminate in a dance of death were it not so life-affirming. Gardiner’s tempo for the second-movement Allegretto is significantly slower than the metronome (as witness Chailly) but the relationship between the wind and strings (period instruments far more equal in the balance) and the give and take between subject and countersubject lends an expressive mobility. There’s still an air of slow dance about it, breathlessly superseded by the scherzo with its whiplash reflexes (so much speedier with a leaner, meaner ensemble) and the excitement of sustained natural trumpets in the Trio. The hair-raising reiterations of the finale, driven to the point of exhaustion – the most exhilarating kind of exhaustion – are accentuated by the immediacy of the sound, and the penultimate piledriving climax and coda are absolutely thrilling, with brazen horns again dominating ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Symphony No 6

(Coupled with Schubert's Symphony No 5) Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Karl Böhm

DG

Karl Böhm’s Beethoven is a compound of earth and fire. His VPO recording of Beethoven’s Sixth of 1971 dominated the LP catalogue for over a decade, and has done pretty well on CD on its various appearances. His reading is generally glorious and it remains one of the finest accounts of the work ever recorded. It still sounds well and the performance (with the first-movement exposition repeat included) has an unfolding naturalness and a balance between form and lyrical impulse that’s totally satisfying. The brook flows untroubled and the finale is quite lovely, with a wonderfully expansive climax. The Schubert dates from the end of Böhm’s recording career. It’s a superb version of this lovely symphony, another work that suited Böhm especially well. The reading is weighty but graceful, with a most beautifully phrased Andante (worthy of a Furtwängler), a bold Minuet and a thrilling finale. The recording is splendid. If you admire Böhm this is a worthy way to remember his special gifts.

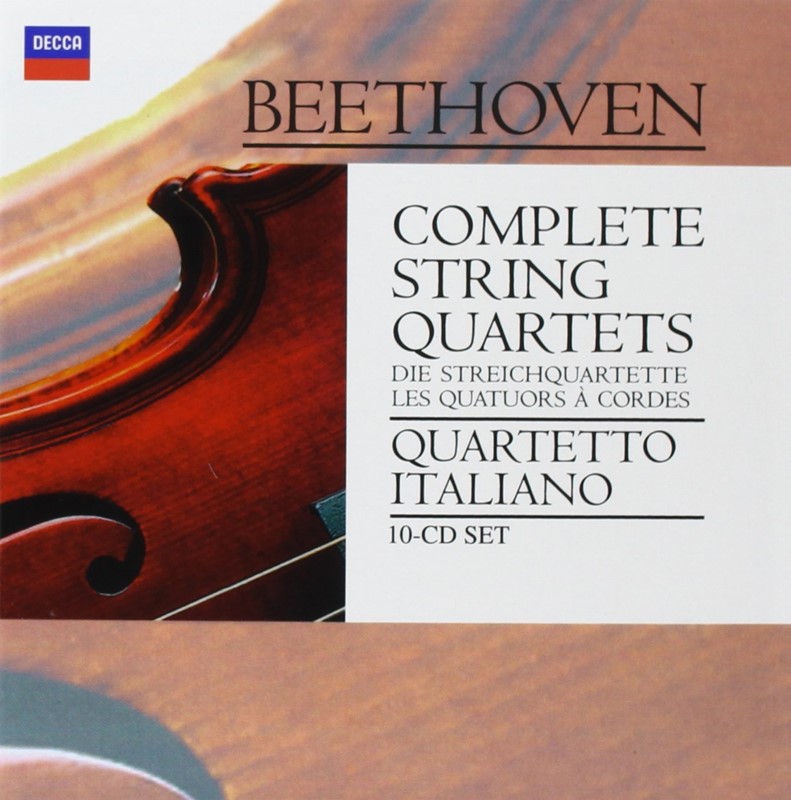

Chamber

Complete String Quartets

Quartetto Italiano

Decca

It goes without saying that no one ensemble can unlock all the secrets contained in these quartets. The Quartetto Italiano’s claims are strongest in the Op 18 Quartets. They offer eminently civilised, thoughtful and aristocratic readings. Their approach is reticent but they also convey a strong sense of making music in domestic surroundings. Quite frankly, you couldn’t do very much better than this set. In the middle-period quartets the Italians are hardly less distinguished, even though there are times when the Végh offer deeper insights, as in the slow movement of Op 59 No 1. Taken in isolation, however, the Quartetto Italiano remain eminently satisfying both musically and as recorded sound. As far as sound quality is concerned, it’s rich and warm. In Opp 74 and 95, they more than hold their own against all comers. These are finely proportioned readings, poised and articulate.

The gain in clarity because of the remastering entails a very slight loss of warmth in the middle register, but as recordings the late quartets, made between 1967 and 1969, can hold their own against their modern rivals. Not all of these received universal acclaim at the time of their first release. The opening fugue of Op 131 is too slow at four-in-the-bar and far more espressivo than it should be, but, overall, these performances still strike a finely judged balance between beauty and truth, and are ultimately more satisfying and searching than most of their rivals.

☆

String Quartets, Vols 1-3

Takács Quartet

Decca

Review of Vol 3 - The Late Quartets: Late Beethoven is all about contrasts: prayer and play, structural logic and emotional candour, relative convention and daring. Wherever you join the journey, some rogue idea invariably lies ready to pounce: the way Op 127’s Andante con moto chugs along happily then abruptly turns to face us with a weeping confession. Similarly halfway through Op 130’s Cavatina; and Op 131’s Scherzo gate-crashes the tale of the preceding variations. Then there’s the zany humour of the other scherzi – from Opp 127 and 135 especially – or the indescribable feeling of release after the opening hymn in Op 132’s Adagio. All this conceived in the prison of deafness, perhaps the greatest of all musical miracles.

Readers who know these works have little use for such guidelines and yet interpreters have to think harder; they need to convey what at times sounds like a stream of musical consciousness while respecting the many written markings. The Takács do better than most. For openers, they had access to the new Henle Edition and have made use of some textual changes (an E replacing a G at 8’13” in the first movement of Op 132, for example) – nothing too drastic but encouraging evidence of a good musical conscience. In Op 130 they take the long first-movement exposition repeat, using the Grosse Fuge as the rightful finale (Beethoven’s original intention) which, in the context of their fiery reading of the fugue, works well. Contemporary incredulity at the sheer scale and complexity of the fugue caused Beethoven to offer a simpler alternative finale (the last thing he wrote) in which the Takács again play the repeat, which helps balance the ‘alternative’ structure.

The Takács evidently appreciate this music both as musical argument and as sound. Try their glassy sul ponticello at the end of Op 131’s Scherzo, or the many instances where plucked and bowed passages are fastidiously balanced. Attenuated inflections are honoured virtually to the letter, textures carefully differentiated, musical pauses intuitively well-timed and inner voices nearly always transparent.

The F major Quartet’s opening Allegretto has an almost Haydnesque wit about it and, although I would have welcomed a more furioso approach to the first movement of the Serioso (Op 95), the sum effect is still impressive. The Takács are conscientious without sounding overly reverential; they know how to ease the tempo momentarily with such subtlety that, unless you’re consciously analysing each phrase, you would never realise (there are instances in Op 132’s Adagio). As to their pooled tone, the overall impression is lean but expressive, with sweetness kept within bounds and only András Fejer’s cello occasionally sounding reticent. Where Beethoven cues a savage attack, he gets it, but when the heart rules, as it so often does in these works, the Takács take his lead there, too.

Beethoven’s late quartets are the ultimate examples of music that is so great that, as Artur Schnabel famously suggested, no single sequence of performances could ever do them full justice. Still, this set comes close and completes one of the best available cycles, possibly the finest in an already rich digital market, more probing than the pristine Emersons or Alban Bergs (live), more refined than the gutsy and persuasive Lindsays, and less consciously stylised than the Juilliards (and always with the historic Busch Quartet as an essential reference) – at no point did I feel the Takács significantly wanting. They do Beethoven proud and no one could reasonably ask for more. Rob Cowan (May 2005)

☆

String Quartets, Op 18

Tokyo Quartet

Harmonia Mundi

Much as I have enjoyed other digital recordings of Beethoven’s first quartets by (for example) the Takacs and Lindsay Quartets, this new Tokyo set just about pips all rivals to the post. The reason is primarily one of balance, not only within the group itself but also in terms of overall musical judgement – whether relating to tempo, dynamics or emphases, or simply the way the players combine a sense of classical style with an appreciation of Beethoven’s startling originality. Even as early as No 1’s pensive opening, you notice how skilfully rests are being gauged, contrasts in colour and inflection, too: the way the clipped first motif leads into its sweetly imploring extension a couple of bars later. The Scherzo’s skipping gait, incisive but lightly dispatched, is another source of pleasure, and so is the seemingly effortless swirl of the closing Allegro. The old quartet cliche about “leaning together” is here a principal attribute. Try the first movement of Op 18 No 2 at 3'56": this could be one person playing.

The qualifying ma non tanto of the C minor’s opening Allegro is pointedly observed: dramatic impact is sustained while composure is maintained. I love the crispness of the Andante scherzoso and the cannily calculated crescendi at the start of the finale. Few ensembles have characterised the A major’s cantering first idea as happily as the Tokyos do here, while the ethereal and texturally variegated middle movements anticipate the very different world of Beethoven’s “late” quartets. Beautifully blended recordings, too: if you’re after a top-ranking digital set of Op 18, you couldn’t do better – though placing them in the context of a complete cycle is rather more difficult until the late quartets appear. Certainly I don’t recall the Tokyo’s latest “middle” quartets being quite as good as this. Rob Cowan (February 2008)

☆

Late String Quartets

Alban Berg Quartett

Warner Classics

The 1984 Gramophone Award in the chamber-music repertory went to the Lindsay Quartet's set of the late Beethoven quartets and it is a measure of the inexhaustibility of these great works that they have also claimed 1985's vote. The Alban Berg are the first to give us them on CD, and the medium certainly does justice to the magnificently burnished tone that the Alban Berg command, and the perfection of blend they so consistently achieve. In terms of sheer technical address, tonal finesse and balance, they enjoy a superiority over almost every other ensemble of their generation. (Indeed some listeners, particularly those brought up on the Busch or Vegh Quartets, may find the sheer polish of their playing gets in the way, for this can be an encumbrance; late Beethoven is beautified at its peril). But so far as sheer quartet playing is concerned, it is likely to remain unchallenged. Robert Layton (1985)

☆

Late String Quartets

Busch Quartet

Warner Classics

Up to a point the length of a review should denote importance – and were this the case, this notice ought to occupy many pages! This is an indispensable set – as revealing of the Beethoven quartets as Schnabel is of the sonatas, and if it were ever correct to speak of any performances as definitive, this is an instance when one might be tempted to do so. The Busch's Beethoven set standards by which successive generations of quartets were judged – and invariably found wanting! Their insight and wisdom, their humanity and total absorption in Beethoven's art has to my mind never been surpassed and only sporadically matched, even by such modern ensembles as the Vegh and the Lindsay!

These performances are so superb that despite their sonic limitations I still think it possible to recommend them to younger non-specialist collectors, even in these days of the Compact Disc. Of course, there are the occasional portamentos that were in general currency in the 1930s but are unfashionable now, but I can't say that I find them irksome. Whatever set you may already have, be it the Hollywood, the Lindsay, the Alban Berg or the Quartetto Italiano, you will not regret adding this to your collection. Robert Layton (November 1985)

☆

String Trios, Op 9 No 1, Op 9 No 3, Op 3

Leonid Kogan vn Rudolf Barshai va Mstislav Rostropovich vc

Supraphon

Here is the latest instalment of Supraphon’s issue of classic concerts given in Prague in the 1950s and ’60s. This one dates from June 2, 1960, at the Prague Spring International Music Festival. And what a line-up: three supreme Soviet artists, for whom Czechoslovakia represented a taste of freedom while the West remained out of bounds. And there’s freedom aplenty in these vigorous, highly charged performances: just sample the concluding Presto of Op 9 No 1 or the opening movement of the E flat major Trio, Op 3. These are strong-jawed readings with a great sense of purpose and, even when some of the details are a bit shaky (and tuning and ensemble less than pristine), they are never less than compelling ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Complete Works for Cello & Piano

Adrian Brendel vc Alfred Brendel pf

Philips

The Brendels, father and son, give us Beethoven’s complete works for piano and cello. You’ll have to search long and hard to hear performances of a comparable warmth and humanity or joy in music-making. Sumptuously recorded and lavishly presented (including engaging family photographs), the sonatas are offered in a sequence that gives the listener an increased sense of Beethoven’s awe-inspiring scope and range.

CD 1 juxtaposes early, middle and late sonatas with a joyous encore in the Variations on Mozart’s ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’. CD 2 gives us the Variations on ‘See the conqu’ring hero comes’ from Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus, continues with the remaining two sonatas and ends with the other Magic Flute Variations, on ‘Bei Männern’.

Pianist and cellist are united by a rare unity of purpose and stylistic consistency, whether in strength and exuberance, an enriching sense of complexity or in other-worldly calm (often abruptly terminated). What eloquence they achieve in the opening Adagio of the Second Sonata, what musical energy in the following Allegro molto tanto presto, instances where Beet-hoven’s volatility is always tempered by the Brendels’ seasoned musicianship ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Complete Works for Cello & Piano

Xavier Phillips vc François-Frédéric Guy pf

Evidence Classics

This is the third instalment in François-Frédéric Guy’s traversal of Beethoven and the first to delve into the chamber music. He is well matched in intellect, musicianship and temperament by cellist Xavier Phillips as they journey from the ridiculous (the Variations on ‘See the Conqu’ring Hero Comes’, in which Guy dispatches the virtuoso piano part with complete aplomb, to delectable effect) to the sublime (the Op 102 Sonatas). The two sets of variations on themes from Mozart’s Magic Flute are a very different proposition from the ‘Conqu’ring Hero’ but just as persuasive, with the Op 66 set given a particularly sparkling reading.

Competition is of course thick on the ground, not least from Isserlis and Levin (playing a tremendously characterful McNulty fortepiano), which was an obvious choice for Record of the Month in February 2014. But Phillips and Guy deserve that accolade just as richly and their utterly different sound world is equally riveting.

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Cello Sonatas

Steven Isserlis vc Robert Levin fp

Hyperion

A cellist who tends towards introversion; a fortepianist who tends the other way. Put them together and something magical happens within the tensions they engender. Beethoven’s directions for the introduction to Op 102 No 1 are explicit – Andante, softly singing, sweetly, tenderly – and Steven Isserlis, playing a gut-strung 1726 Stradivarius, invokes its beauty in hushed, withdrawn tones. Robert Levin, the moderator on Paul McNulty’s copy of a 1805 Walter & Sohn instrument equalising dynamics, matches him in essence and aura. Think of repose in C major for 27 bars until the switch to the main movement; and the sudden shock of a fortissimo chord in A minor is ruder than it would be on a modern piano. No politesse from Levin. What follows is an untrammelled Allegro vivace, two-in-a-bar as marked, tempo changes graphic, every sforzando or accent stabbing the texture, Isserlis unfurling the vehemence also implicit in his lines.

Recover from the onslaught and return to the beginning, to Op 5 No 1. Repose in C major wasn’t a one-off. It manifests itself again, but now in F major and at a slower tempo, Adagio sostenuto. Isserlis has the theme but Levin is no mere accompanist, fastidious in his role as a partner yet one who never overwhelms the cello, even in the chords and roulades during a brief spell of agitation towards the end of this introduction. Rapid pacing isn’t demanded in the ensuing Allegro – now a plain instruction without an oft-added stipulation, and in common time – of mercurial moods ever present; and laid bare by a duo with no inhibitions about extremes in expressive flexibility.

What did Beethoven often add? Try Allegro molto più tosto presto in the first movement of Op 2 No 2. Pretty quick, pretty specific about how quick too; but Isserlis and Levin are also thoughtful in ensuring that the running triplets for the keyboard aren’t reduced to a frantic, unchecked clatter. Yet power and thrust are unassailable, reinforced by lacerating bowing from Isserlis in the development where screws are tightened – in a movement believed to be one of Beethoven’s most notable achievements, no less so for its expectantly prefaced, grandly fantasia-like 44-bar Adagio sostenuto ed espressivo, for Isserlis and Levin an arch, declamatory and lyrical. With something more – a trenchant edge, probably arising from the timbres of the fortepiano, its light action and fast transients ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Violin Sonatas, Vols 1-3

Alina Ibragimova vn Cédric Tiberghien pf

Wigmore Hall Live

Review of Vol 3: This third disc concludes Ibragimova and Tiberghien’s live set of the Beethoven sonatas. The qualities of the earlier instalments (8/10, 12/10) – polished technique, spontaneity and deep engagement with the music – are as strongly apparent here. One small illustration will demonstrate the special character of these performances. The fourth of the final variations of Sonata No 6 begins with three unaccompanied violin chords played piano. Often, violinists seem embarrassed by these, or else create a somewhat eccentric effect. Not so Alina Ibragimova, who gives them the character of tentative, fearful steps into the unknown, to be reassured by Tiberghien’s suave reply. The following minor-key variation shows how both players can bring flexibility and fluidity to their performance, with the confidence that they will be sympathetically accompanied.

By comparison, the excellent studio set by Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov appears more studied. In the middle section of Sonata No 3’s Adagio, each of their perdendoso phrases ends in a ghostly whisper – a wonderful effect. Ibragimova and Tiberghien don’t attempt anything so extreme but their playing has a powerful sense of progress through the series of modulations, born, I imagine, out of the intensity of live performance. In the finales of this sonata and of the Kreutzer, Faust and Melnikov are slightly faster and more brilliant but Tiberghien and Ibragimova, with superb poise and control, appear more carefree and joyful. And their account of the Kreutzer’s first movement, with its Furtwängler-like broadening at the climax of the coda, unmistakably exposes the music’s portrayal of emotional turmoil. Duncan Druce (July 2011)

☆

Complete Violin Sonatas

Isabelle Faust vn Alexander Melnikov pf

Harmonia Mundi

The musical sleight of hand used by these expert players to focus the very different character of each sonata is in itself cause for wonder. Though quite different as musical personalities – Faust, subtle and quietly formal; Melnikov, a master of the meaningful pause – the combination of the two fires a laser between the staves. Fleetness and elegance are very much to the fore in the Op 12 set, beauty of tone, too, especially in the First Sonata.

The Spring Sonata is lyrical and playful, the opening as easy-going as anyone could wish, the Adagio like a song without words, Faust’s tone warming but relatively restrained, Melnikov a discreetly supportive partner. The more dramatic sonatas are muscular yet very light on their feet. The A minor, Op 23, is Sturm und Drang with a vengeance, and both players make a point of (metaphorically) pursing their lips: in fact, you sometimes feel that what isn’t being expressed outweighs what is. Of the three Op 30 sonatas, the kernel is the C minor, where Faust and Melnikov strike a perfect balance between fire and ice. Their little “freedoms” are very telling but although the shaping of phrases is obviously the product of considered teamwork, you never feel that they’re playing safe. Cautious Beethoven makes for a very passionless partnership, and there’s no sense of that ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

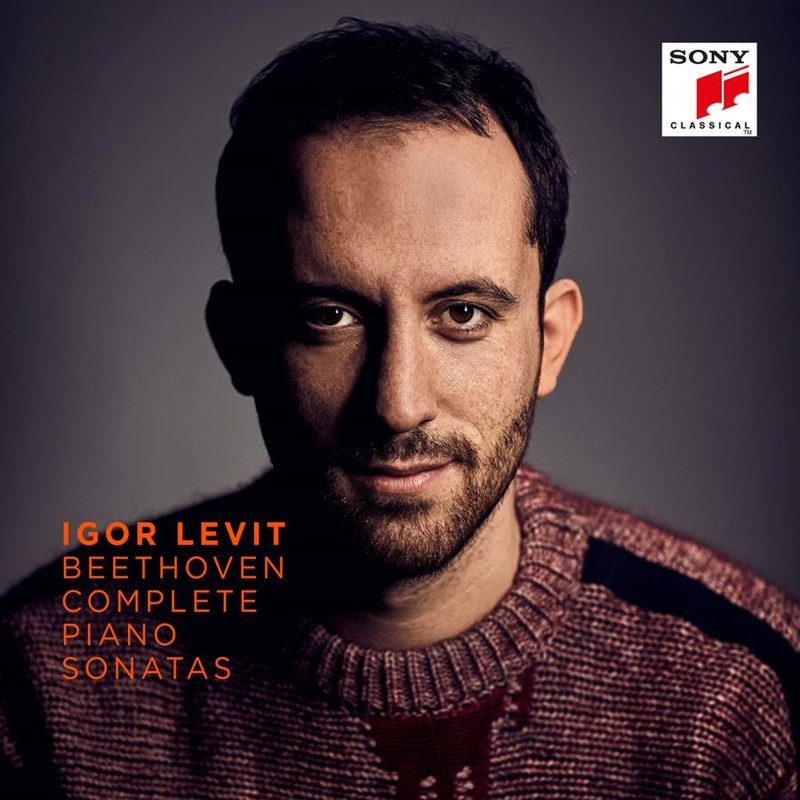

Instrumental

Complete Piano Sonatas

Igor Levit pf

Sony Classical

A highlight is the Waldstein, the repeated C major left-hand chords underpinning a tensile energy that runs through the entire opening movement. But it’s not about momentum: Levit colours and shapes it with such finesse – withdrawing the sound to a whisper and then building to a great billowing wave. The Adagio molto is remarkable in the way he stills the mood, conjuring an atmosphere that sounds almost like a postscript to Schubert’s Winterreise. As the music gradually comes back to life his finale is engagingly ebullient.

It also says much for Levit’s maturity that the last five sonatas still sound very much of a piece in terms of the way he thinks. Yes, there are moments where I don’t entirely agree with his decisions – the opening of Op 109 is a little careful-sounding, while moments in the variations of Op 111’s Arietta are a touch on the slow side – but the Hammerklavier’s fugue is still a thing of magnificent power and, above all, there’s that sense of being completely at one with Beethoven himself. And that, in the end, is what makes this such a magnificent achievement ...

☆

Complete Piano Sonatas

Wilhelm Kempff pf

DG mono

Wilhelm Kempff was the most inspirational of Beethoven pianists. Those who have cherished his earlier stereo cycle for its magical spontaneity will find Kempff’s qualities even more intensely conveyed in this mono set, recorded between 1951 and 1956. Amazingly the sound has more body and warmth than the stereo, with Kempff’s unmatched transparency and clarity of articulation even more vividly caught, both in sparkling Allegros and in deeply dedicated slow movements. If in places he’s even more personal, some might say wilful, regularly surprising you with a new revelation, the magnetism is even more intense, as in the great Adagio of the Hammerklavier or the final variations of Op 111, at once more rapt and more impulsive, flowing more freely. The bonus disc, entitled ‘An All-Round Musician’, celebrates Kempff’s achievement in words and music, on the organ in Bach, on the piano in Brahms and Chopin as well as in a Bachian improvisation, all sounding exceptionally transparent and lyrical. Fascinatingly, his pre-war recordings of the Beethoven sonatas on 78s are represented too. Here we have his 1936 recording of the Pathétique, with the central Adagio markedly broader and more heavily pointed than in the mono LP version of 20 years later.

☆

Complete Piano Sonatas

Artur Schnabel pf

EMI/Warner/Musical Concepts

Schnabel was almost ideologically committed to extreme tempos; something you might say Beethoven’s music thrives on, always provided the interpreter can bring it off. By and large he did. There are some famous gabbles in this sonata cycle, notably at the start of the Hammerklavier, with him going for broke. In fact, Schnabel also held that ‘It is a mistake to imagine that all notes should be played with equal intensity or even be clearly audible. In order to clarify the music it is often necessary to make certain notes obscure.’ If it’s true, as some contemporary witnesses aver, that Schnabel was a flawless wizard in the period pre-1930, there’s still plenty of wizardry left in these post-1930 Beethoven recordings. They are virtuoso readings that demonstrate a blazing intensity of interpretative vision as well as breathtaking manner of execution. Even when a dazzlingly articulate reading like that of the Waldstein is home and dry, the abiding impression in its aftermath is one of Schnabel’s (and Beethoven’s) astonishing physical and imaginative daring. And if this suggests recklessness, well, in many other instances the facts are quite other, for Schnabel has a great sense of decorum. He can, in many of the smaller sonatas and some of the late ones, be impeccably mannered, stylish and urbane. Equally he can be devilish or coarse. At the other extreme, he’s indubitably the master of the genuinely slow movement. For the recorded sound, there’s nothing that can be done about the occasional patch of wow or discoloration but, in general, the old recordings come up very freshly.

☆

Complete Piano Sonatas

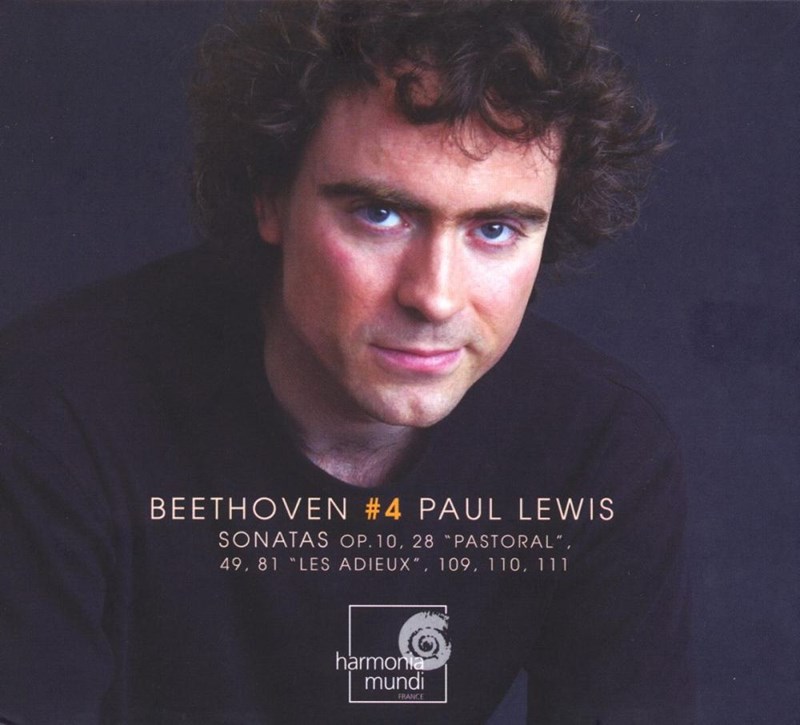

Paul Lewis pf

Harmonia Mundi

Review of Vol 4: Only an extended essay could do justice to the fourth and final volume of Paul Lewis’s Beethoven sonata cycle. But space, sometimes the critic’s friend, here his enemy, forbids much beyond generalisation when faced with such overall mastery and distinction. Like me, you may well cherish your beloved sets by Schnabel, Kempff and Brendel (to name but three), but Lewis surely gives you the best of all possible worlds; one devoid of idiosyncrasy yet of a deeply personal musicianship.

Where else can you hear Op 10 No 2’s madcap finale given with such unfaltering lucidity and precision? Try Op 28’s finale for an ultimate pianistic and musical finesse or the opening Allegro where Lewis makes you conscious of how the music’s gracious and mellifluous unfolding is momentarily clouded by mystery and energised by drama. In such hands the final pages of Op 111 do indeed become “a drift towards the shores of Paradise” (Edward Sackville-West) and throughout all these performances you sense how “the great effort of interpretation” (Michael Tippett) is resolved in playing of a haunting poetic commitment and devotion. Such playing is hardly for lovers of histrionics or inflated rhetoric, but rather for those in search of other deeper, more refreshing attributes, for Beethoven’s inner light and spirit. Somehow Lewis’s quiet and distinctive voice can lift even the most familiar phrase on to another sphere and his playing throughout, shorn of accretion, makes all these sonatas shine with their first radiance and eloquence. Admirably recorded, this three-disc set is crowned with a scholarly and illuminating essay by Jean-Paul Montagnier. Bryce Morrison (June 2008)

☆

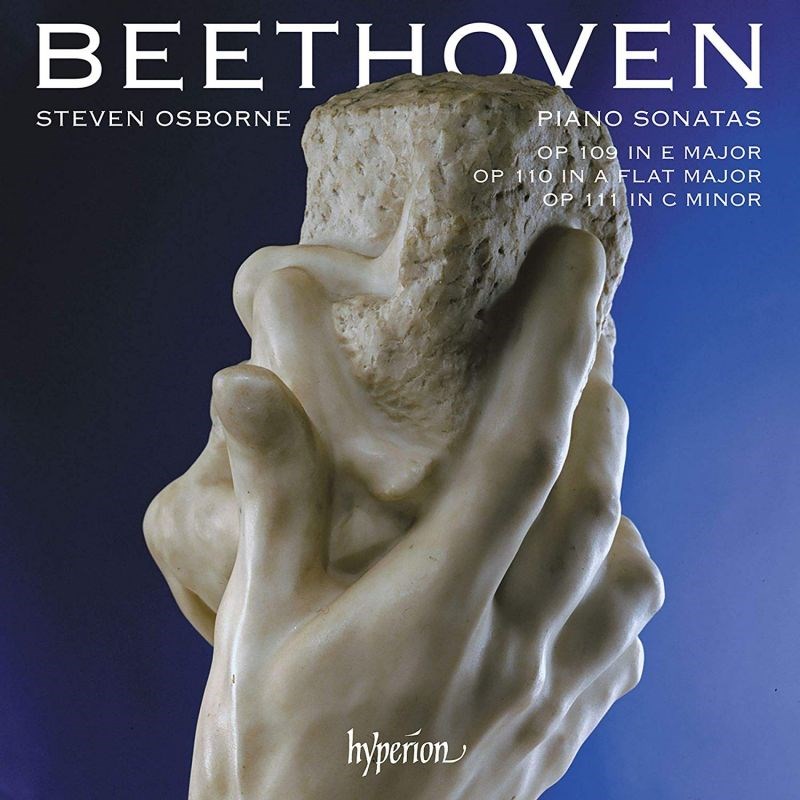

Piano Sonatas Nos 30-32

Steven Osborne pf

Hyperion

I was much looking forward to getting my hands on this CD, having chosen Steven Osborne’s previous Beethoven sonata disc, featuring a dangerous and profound Hammerklavier, as my Critics’ Choice in 2016. From the first note, Osborne’s kinship with the composer is everywhere apparent and he conveys the vast contrasts of the last three sonatas unerringly. When I was doing a Building a Library on Op 109 last year for BBC Radio 3, I was looking for a combination of wonder and fantasy that didn’t tip over into late Romanticism in the first movement, fearsome firepower without edge in the Prestissimo and a Classicism to the theme of the finale’s variations. And that is exactly what we get here.

Sample Osborne’s way with the theme of the finale: it has an outward simplicity from which the variations can grow, yet listen more closely and you’ll detect the endlessly varied colourings and subtle changes of dynamics and phrasing, making the repeats truly developmental. Impressive too is the way the variations unfold with complete inevitability: from the octave right-hand leap in the first, which is given without mannerism, via the perfect accord between the hands in the dotted articulation of the second, which contrasts beautifully with the more extended line of the third... Harriet Smith

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

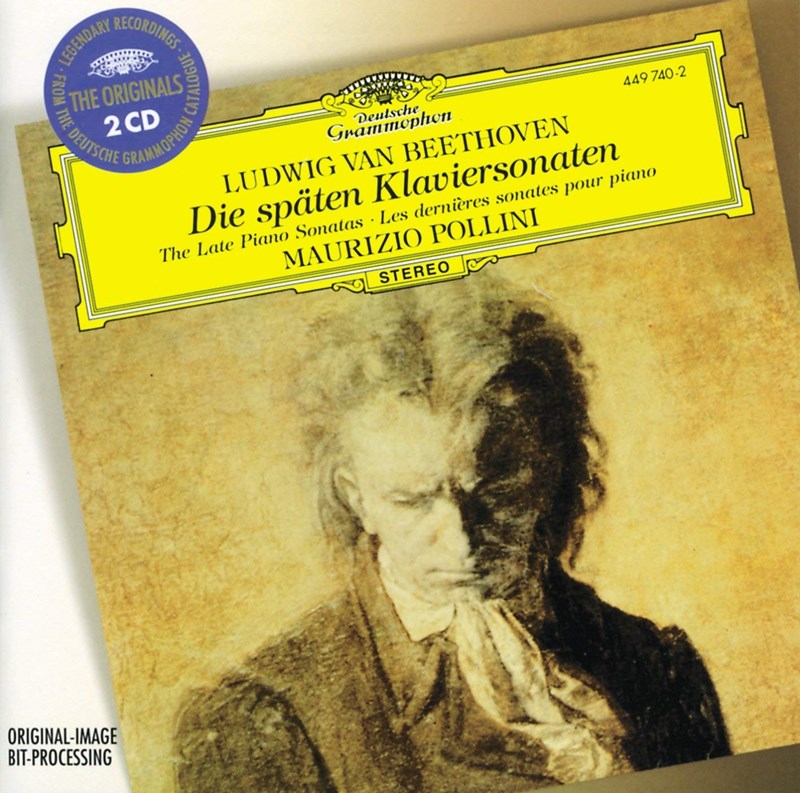

Piano Sonatas Nos 28–32

Maurizio Pollini pf

DG

Make no mistake, this is playing of the highest order of mastery. Indeed, I am not sure that Pollini’s account of the Hammerklavier is not the most impressive currently before the public, though the instant such thoughts are penned, the noble performances of Eschenbach, Arrau, Brendel and Ashkenazy spring to mind. Yet not even beside such giants as these as well as Solomon, Kempff and perhaps even Schnabel does Pollini’s achievement pale.

If Schnabel’s Hammerklavier was not one of the triumphs of his pioneering cycle, its surface roughness worked in its favour in that the listener was never distracted from the spirit by the beauty of the letter. Pollini’s account is simply staggering, for if there are incidental details which are more tellingly illuminated by other masters, no performance is more perfect than this new version. Superb rhythmic grip, sensitivity to line and gradation of tone, a masterly control of the long paragraph; all these are features of this remarkable reading. In the slow movement the sublime outpouring of lyrical feeling beginning at bar 27 shows Pollini’s peerless sense of line and eloquence of spirit, though memories of Arrau who fashions this passage with great poetry are not banished. John Ogdon’s account has a splendidly withdrawn feeling at this point and a raptness and tranquillity that I greatly admire. No one, however, quite matches Pollini’s stunning finale: its strength and controlled power silence criticism. There is no doubt, I think, that this is great piano-playing. Robert Layton (January 1978)

☆

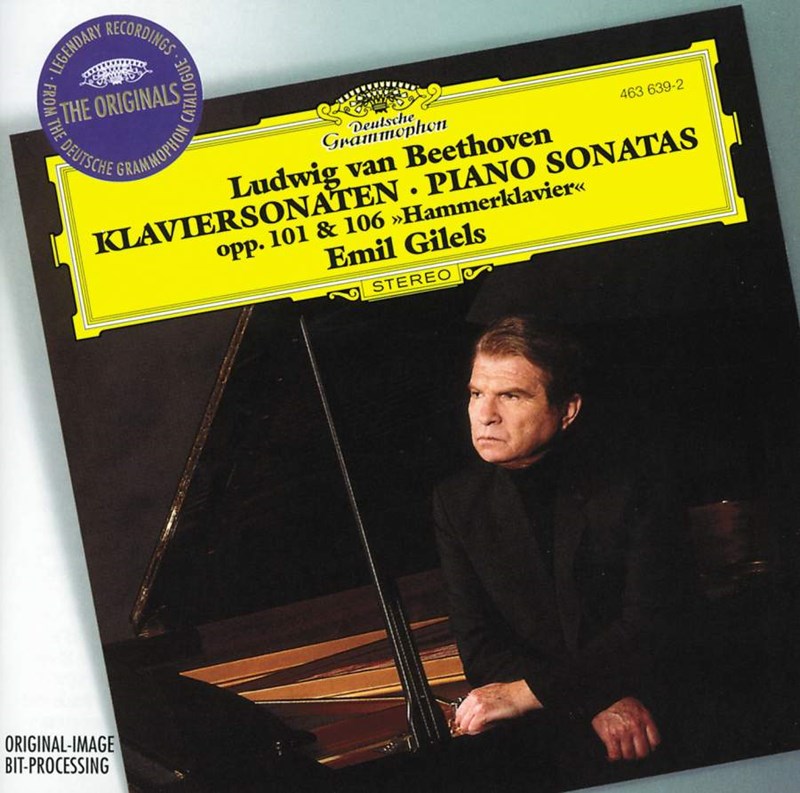

Piano Sonata No 29, 'Hammerklavier'

Emil Gilels pf

DG

Few works of music stimulate active and stressful thinking - anxious thought complementing the music's search for resolvable sounds - than the Hammerklavier. Nor is it a work which is easily mastered physically. (Pollini, on DG, strikes me as being too obviously masterful; Brendel, on Philips, less so.) Of all pianists, Schnabel (on his 1935 HMV recording) perhaps comes closest to conveying a reckless, all-or-nothing mood, allied to a terrier-like grasp of argument and a sure instinct for the work's persistent striving for release into uninhibited song. Yet there are scrambles and mistakes in his performance which were avoided, with minimal loss to the music's headlong impetus, in the famous 1956 Solomon recording, whose absence from the catalogue is much to be regretted. Like Solomon, Gilels gives us an outstanding reading of the vast slow movement. The tempo is spacious, apt to Gilels's mastery of the music's anisometric lines and huge paragraphs, paragraphs as big as an East Anglian sky. Few pianists since Solomon have come near to matching Gilels's ability to touch off the rapt, disburdened beauty of these lofty Beethovenian cantilenas.

The search for lyric release is something which Gilels seems particularly to stress. The arrival – introit, rathe r- of the finale's D major subject, Tovey's "Still, Small Voice" after the Fire, is here a moment that is specially cherishable, the more so as the fugue and the subsequent aggressive peroration are played by Gilels with a directness and lucidity which contrasts interestingly with his sophisticated and equivocal treatment of the opening Allegro movement. There, we have a sense of impetus and attack (Gilels's sheer pianistic command compensating for a tempo 42 minims a minute below Beethoven's startling and plausible minim = 138) though when we reach the gracious second subject in G, rhythmic motion is not so much suspended as upstaged by the first intimations of the music's surprising capacity for feminine songfulness.

The Scherzo, as befits its character, is also equivocal; the playing of the Trio and the dance's quietly elaborated reprise is a rare treat for the ear, though the tempo seems slow for so obviously ironic a piece. It takes a major pianist standing outside the Viennese tradition to see the volatile and ageing Beethoven subsuming gamesome Classical ironies in Romantic pathos and a feeling of personal travail.

There is, though, nothing effete about the totality of Gilels's reading. Formidably in command of the music, he neither subjects the notes to his virtuosic will, nor demeans his own technique by mimetic attempts at audible disorder. Disturbingly aware, in the first movement, of what he suggests are unstable fancies informing the work's manic oscillations, Gilels proceeds to achieve a troubled coherence in the brilliantly executed coda of the finale where his extraordinary technique allows the music's evident ferocity to be tempered by Orphic assurance.

It is, in fine, an absorbing and ambiguous reading. At times it is a model of lucidity, arguments and textures appearing as the mechanism of a fine Swiss watch must do to a craftsman's glass; yet the reading is also full of subversive beauty, the finely elucidated tonal shifts confirming Charles Rosen's assertion that Beethoven's art, for all its turbulence, is here as sensuous as a Schubert song.

The recording is limpid and resolute, with something of the character and atmosphere of Wilhelm Kempff's celebrated recordings of this endlessly challenging, endlessly fascinating work. Richard Osborne (December 1983)

☆

Piano Sonatas Nos 27-32

Solomon pf

Warner Classics

Solomon’s 1952 recording of the Hammerklavier Sonata is one of the greatest of the century. At the heart of his performance there’s as calm and searching an account of the slow movement as you’re ever likely to hear. And the outer movements are also wonderfully well done. Music that’s so easy to muddle and arrest is here fierily played; Solomon at his lucid, quick-witted best.

The CD transfer is astonishing. It’s as though previously we have merely been eavesdropping on the performance; now, decades later, we’re finally in the presence of the thing itself. It’s all profoundly moving. What’s more, EMI has retained the juxtaposition of the 1969 LP reissue: Solomon’s glorious account of the A major Sonata, No 28 as the Hammerklavier’s proud harbinger. We must be grateful that Solomon had completed his recording of these six late sonatas before his career was abruptly ended by a stroke in the latter part of 1956.

The Sonatas Nos 27 and 31, were recorded in August 1956. In retrospect the warning signs were already there; yet listening to these edited tapes you’d hardly know anything was amiss. There’s the odd fumble in the Scherzo of No 31; but, if anything, the playing has even greater resolve, both in No 31 and in a songful (but never sentimental) account of No 27. The recordings of Nos 30 and 32 date from 1951. Sonata No 30, is very fine; No 32 is, by Solomon’s standards, a shade wooden in places, both as a performance and as a recording. Still, this is a wonderful set, and very much a collectors’ item.

☆

Diabelli Variations

Stephen Kovacevich pf

Onyx

Wilhelm von Lenz described the Diabelli Variations as “a satire on their theme”. It’s an apt summation, for what could be more remarkable than something as inherently mediocre as Diabelli’s theme giving voice to one of the greatest – some would argue the greatest – work ever written for solo piano?

Kovacevich writes in his introduction to this new set that it was the Diabelli Variations – via the Serkin recording – that first made him love Beethoven. It’s a reading that still holds its head high today, and just a decade later, in 1968, Kovacevich set down his own recording, rightly acclaimed and something of a calling-card for the young pianist. But what of this new performance, made 40 years later? What is immediately striking is the sense of a cumulative whole, the tension and indeed speed with which he approaches the work. The work’s juxtapositions of the sublime and the ridiculous are presented with a vividness that sounds more live than studio-bound ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

Vocal

Songs

Stephen Genz bar Roger Vignoles pf

Hyperion

The 26-year-old Erfurt-born baritone Stephan Genz is in the first bloom of his youthful prime. His Schumann Liederkreis, Op 24 (5/98) was the first recording to give serious warning of the distinctive lyric ardour and keen intelligence of his artistry; and now Beethoven’s setting of Goethe’s ‘Mailied’ (Op 52 No 4), with its lightly breathed, springing words, could have been written with Genz in mind.

Four more Goethe settings celebrate the great man’s 250th anniversary year. Roger Vignoles, Genz’s regular accompanist, contributes an irresistible bounding energy and even a sense of mischief to one of Beethoven’s most spontaneous yet subtle settings, ‘Neue Liebe, neues Leben’; and an elusive sense of yearning is created as the voice tugs against the piano line in ‘Sehnsucht’ ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Choral Fantasia. Triple Concerto. Rondo for Piano & Orchestra

Pierre-Laurent Aimard pf Thomas Zehetmair vn Clemens Hagen vc Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Arnold Schoenberg Choir / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Warner Classics

Listening to the opening tutti on this joyful new Triple Concerto, I could just picture Nikolaus Harnoncourt cueing his strings, perched slightly forwards, impatiently waiting for that first, pregnant forte. This is a big, affable, blustery Triple, the soloists completing the sound canvas rather than dominating it, a genuine collaborative effort. So beside the Beethovenian strut to this performance there is poetry too, as at 8’25” where Clemens Hagen wafts in with the principal theme underpinned by gently brushed strings. Then again the modulating sequences from 9’36”, so often crudely hammered home in rival versions, are stylishly shaped, the emphases properly focused, with Aimard clearly centre-stage. And yet thoughtfulness never spells caution (all three works were recorded at concerts in Graz over the last 18 months); Hagen and Thomas Zehetmair throw caution to the winds near the end of the first movement ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

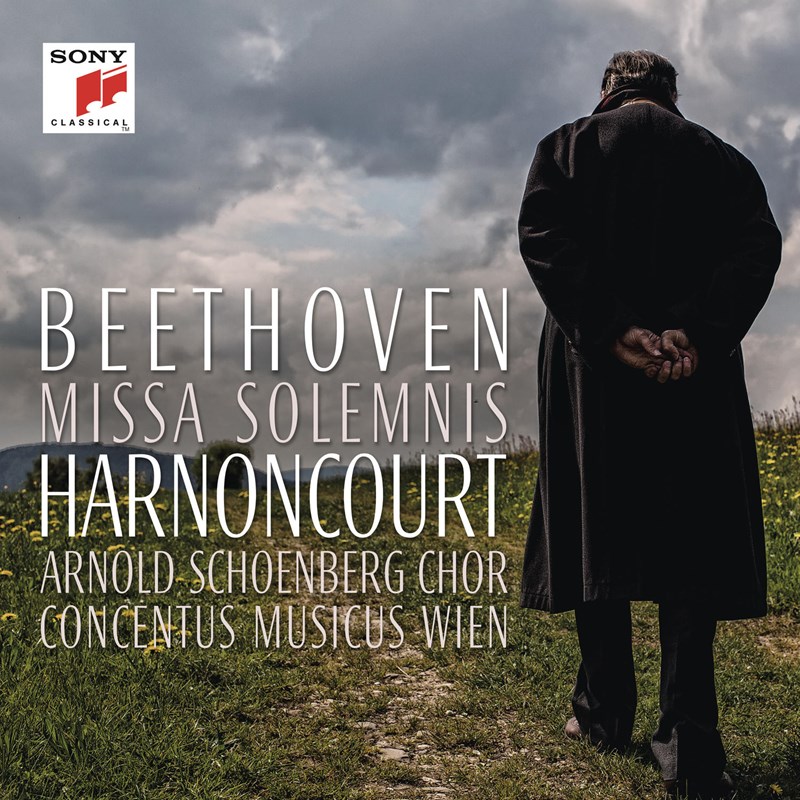

Missa Solemnis

Laura Aikin sop Elisabeth Kulman mez Johannes Chum ten Ruben Drole bass-bar Arnold Schoenberg Choir; Concentus Musicus Wien / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Sony Classical

This is a remarkable account of Beethoven’s Missa solemnis and, in one important respect, an unusual one. For though it is in no sense lacking in drama, it is in essence a deeply devotional reading. And aptly so. ‘Mit Andacht’ – ‘with devotion’ – Beethoven writes time and again during the course of the work.

Where many of the Mass’s most praised interpreters have treated it as a species of music drama, the god Dionysus never far distant, Harnoncourt’s performance has an atmosphere you might more normally expect to encounter when listening to a piece such as the Fauré Requiem. His aim was to ‘develop the work from silence’ and ‘keep the usual frenzied sonorities within bounds’. A search for inner and outer peace – the aspiration Beethoven writes above the opening bars of the ‘Dona nobis pacem’ – is the performance’s ultimate goal ...

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

Opera

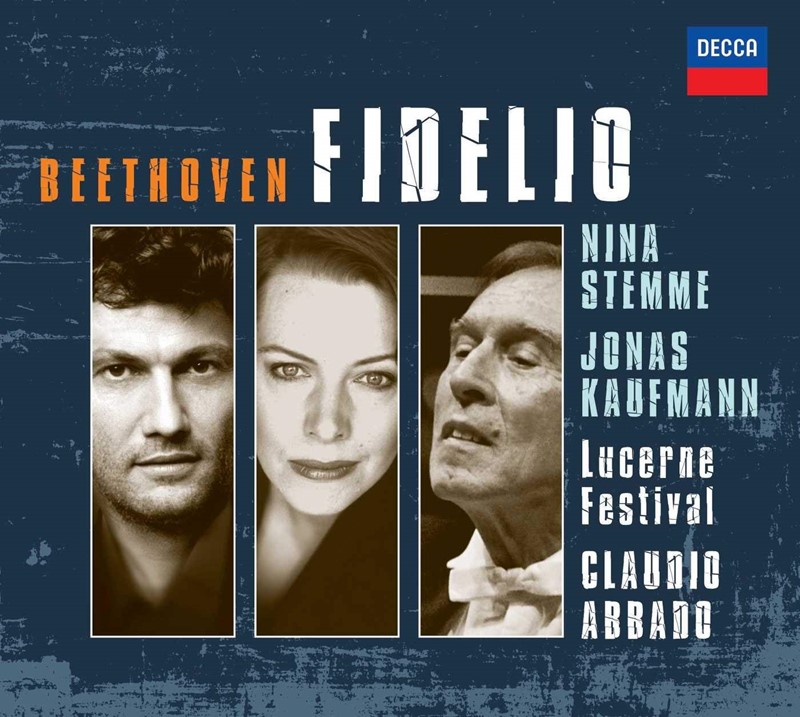

Fidelio

Stemme; Kaufmann; Lucerne Festival Orchestra / Claudio Abbado

Decca

It was Abbado’s second Berlin Philharmonic symphony cycle from 2001 which thrust him more or less unexpectedly into the ranks of the immortals where Beethoven is concerned. And it was seven years after that, in Reggio Emilia in 2008, that he conducted his first Fidelio. Like Furtwängler in his 1953 studio recording, Abbado leads a viscerally charged performance that flies to the very heart of the matter, and does so in a version which, stripping away much of the spoken dialogue, recreates Beethoven’s lofty Singspiel as musical metatheatre.

The recording derives from two semi-staged concert performances, the audience happily sensed but not heard. Technically the recording is first-rate but, then, you need no sonic-stage trickery in the dungeon scene in a performance which reveals as exactingly as this how Beethoven’s own orchestrations are key. One of the many glories of this thrillingly articulated Fidelio is the playing of the basses and lower strings, sharp-featured and black as the pit of Acheron.

Read the full review in the Reviews Database

☆

Fidelio

Jurinac; Vickers; Frick; Hotter; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden / Otto Klemperer

Testament mono