Piano Concertos

Piano Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Denis Matsuev pf Mariinsky Orchestra / Valery Gergiev (Mariinsky)

The B flat minor Concerto has been recorded so many times that you may justifiably ask if we really need another. For an answer, listen to this newcomer. There have been many very great accounts of it – Horowitz / Szell, Argerich / Abbado, Gilels / Mehta among them – but I doubt if you will ever hear it more viscerally thrilling and sumptuously engineered than here. Listening to Matsuev and Gergiev is the aural equivalent of watching Federer and Nadal, friends off the tennis court but ultra-competitive on it, each determined to outdo the other with supreme athleticism and an arsenal of exquisite passing shots.

After a conventional enough introduction, you start to notice deft little touches, such as the weight Matsuev gives to his attack at the top of the keyboard or the darting semiquaver runs at 5'23", which he plays leggiero and with no pedal. Neither protagonist is anxious to linger sentimentally along the way and Gergiev, sometimes routine in concerto recordings, is here fiercely energised – giving as good as he gets, as it were, from his soloist – to the point after the orchestral tutti at 10'55" that you wonder how Matsuev is going to match him. But of course he does, and to hair-raising effect.

Piano Concerto No 1

Yevgeny Sudbin pf São Paulo Symphony Orchestra / John Neschling

Sudbin gives us a Tchaikovsky First of spine-tingling brilliance, poetry and vivacity. This is never the Tchaikovsky you have always known, but an arrestingly novel rethink with the concentration on mercurial changes of mood and direction. Here, amazingly, is one of the most familiar of all concertos rekindled in all its first glory, brimming over with zest and shorn of all the clichés that have adhered to it over the years.

In the first movement Sudbin’s octaves ring out at 10'18" like a giant carillon, while the Andantino’s central prestissimo becomes in such extraordinary hands a true firefly scherzo. Not even Cherkassky at his finest possesed a more elfin sense of difference or caprice.

Piano Concerto No 1. The Nutcracker – Suite, Op 71a (arr Economou)

Martha Argerich, Nicolas Economou pfs Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (DG) Recorded live 1983, 1994

Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto has already appeared twice on disc from Martha Argerich in complementary performances: live and helter-skelter on Philips with Kondrashin, studio and magisterial with Dutoit on DG. Now, finely recorded, here’s a third, live recording with the BPO and Claudio Abbado surpassing even those earlier and legendary performances. Argerich has never sounded on better terms with the piano, more virtuoso yet engagingly human. Lyrical and insinuating, to a degree her performance seems to be made of the tumultuous elements themselves, of fire and ice, rain and sunshine. The Russians may claim this concerto for themselves, but even they will surely listen in disbelief, awed and – dare one say it – a trifle piqued. Listen to Argerich’s Allegro con spirito, as the concerto gets under way, where her darting crescendos and diminuendos make the triplet rhythm speak with the rarest vitality and caprice. Her nervous reaching out towards further pianistic frays in the heart-easing second subject is pure Argerich and so are the octave storms in both the first and third movements that will have everyone, particularly her partners, tightening their seat belts. The cadenza is spun off with a hypnotic brilliance, the central Prestissimo from the Andantino becomes a true ‘scherzo of fireflies’, and the finale seems to dance off the page; a far cry from more emphatic Ukrainian point-making and brutality.

For encores DG has reissued Argerich’s 1983 performance of The Nutcracker where she’s partnered by Nicolas Economou in his own arrangement, a marvel of scintillating pianistic prowess, imagination and finesse.

Piano Concerto No 1

Horowitz; NBC SO / Toscanini (Naxos)

Anyone who was lucky enough to attend Carnegie Hall on April 19th, 1941 will have heard one of the most electrifying Tchaikovsky concerts in living memory. Arturo Toscanini conducted the early Voyevoda Overture, the Pathetique Symphony and the First Piano Concerto with his son-in-law Vladimir Horowitz as soloist (it was the very first time that they had performed the work together). Wartime collectors at least had the chance to hear the famous Horowitz-Toscanini studio recording of the concerto, made during the following month. Nowadays, of course, that RCA classic is considered something of a ‘must’ for piano aficionados, and yet its live predecessor is, if anything, even more spontaneous.

Violin Concerto in D, Op 35

Violin Concerto

Heifetz; Chicago SO / Reiner (RCA)

A performance of outsize personality from Heifetz and Reiner. Coupled with this same partnership’s sovereign account of the Brahms Concerto.

Violin Concerto

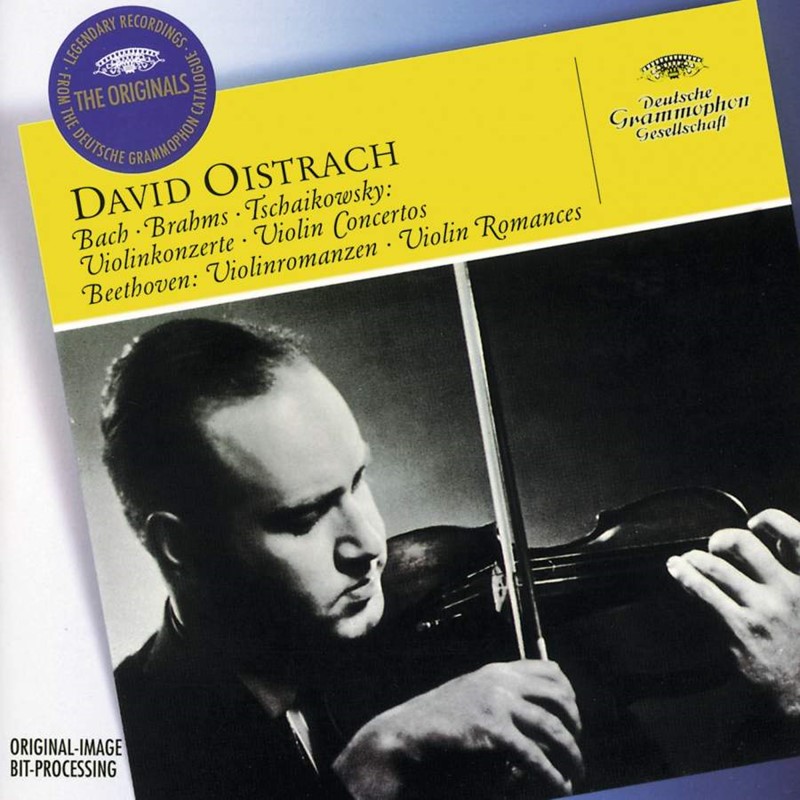

Oistrakh; Staatskapelle Dresden / Konwitschny (DG mono)

It is good here to welcome the mono recordings of the Brahms and Tchaikovsky concertos which David Oistrakh made in February 1954, more volatile readings than those he recorded later, respectively with Klemperer for EMI in the Brahms (3/93) and with Ormandy for CBS in the Tchaikovsky (11/89). Here, working with Konwitschny and the Dresden orchestra, he seems to be more relaxed, more freely expressive, moving easily from dashing bravura to the sweetest lyricism in the first movement of the Brahms, and entering in the slow movement at a faster pace than his conductor, clearly determined to expunge the suspicion of stodginess in the opening tutti. In the finale of the Brahms there is barely any difference in the speed of the opening between Konwitschny or Klemperer, but with Konwitschny Oistrakh feels free to press ahead, where with Klemperer it tends to be the opposite, so that the overall timing for the movement is some 35 seconds longer. In the Tchaikovsky Ormandy is also a more solid interpreter than Konwitschny, and though in the first movement that encourages Oistrakh into deliberate expressive dalliances, generally he is more freely expressive with Konwitschny, and more spontaneous sounding.

Violin Concerto

K-W Chung; LSO / Previn (Decca)

Chung’s engagingly svelte and warm-hearted account has barely aged at all. A longstanding favourite, this, with Previn and the LSO also on top form.

Violin Concerto

J Fischer; Russian National Orch / Kreizberg (Pentatone)

A splendid recording from the hugely impressive Julia Fischer. There’s power and poetry in spades and the orchestra accompany with thrilling commitment.

Symphonies

Complete Symphonies

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan (DG)

Karajan was unquestionably a great Tchaikovsky conductor. Yet although he recorded the last three symphonies many times, he did not turn to the first three until the end of the 1970s, and then proved an outstanding advocate. In the Mendelssohnian opening movement of the First, the tempo may be brisk, but the music’s full charm is displayed and the melancholy of the Andante is touchingly caught. Again at the opening of the Little Russian (No 2), horn and bassoon capture that special Russian colouring, as they do in the engaging Andantino marziale, and the crisp articulation in the first-movement Allegro is bracing. The sheer refinement of the orchestral playing in the scherzos of all three symphonies is a delight, and finales have great zest with splendid bite and precision in the fugato passages and a convincing closing peroration.

The Polish Symphony (No 3) is the least tractable of the canon but again Karajan’s apt tempi and the precision of ensemble make the first movement a resounding success. The Alla tedesca brings a hint of Brahms, but the Slavic dolour of the Andante elegiaco is unmistakeable and its climax blooms rapturously. No doubt the reason these early symphonies sound so fresh is because the Berlin orchestra was not over-familiar with them and clearly enjoyed playing them. The sound throughout is excellent. It gets noticeably fiercer in the Fourth Symphony, recorded a decade earlier, but is still well balanced. The first movement has a compulsive forward thrust and the breakneck finale is viscerally thrilling. The slow movement is beautifully played but just a trifle bland. Overall, though, this is impressive and satisfying, especially the riveting close.

DG has chosen the 1965 recording of the Fifth, rather than the mid-’70s version, and was right to do so. It’s marvellously recorded (in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche): the sound has all the richness and depth one could ask and the performance too is one of Karajan’s very finest. There’s some indulgence of the second-subject string melody of the first movement. But the slow movement is gloriously played from the horn solo onwards, and the second re-entry of the Fate theme is so dramatic that it almost makes one jump. The delightful Waltz brings the kind of elegant warmth and detail from the violins that’s a BPO speciality, and the finale, while not rushed Mravinsky-fashion, still carries all before it and has power and dignity at the close.

The Pathétique was a very special work for Karajan (as it was for the Berlin Philharmonic) and his 1964 performance is one of his greatest recordings. The reading as a whole avoids hysteria, yet the resolution of the passionate climax of the first movement sends shivers down the spine, while the finale has a comparable eloquence, and the March/Scherzo, with ensemble wonderfully crisp and biting, brings an almost demonic power to the coda. Again the sound is excellent, full-bodied in the strings and with plenty of sonority for the trombones.

Symphony No 3, ‘Polish’. Music for the Theatre

Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra / Neeme Järvi (BIS)

Neeme Järvi’s understated cycle of the Tchaikovsky symphonies has certainly accentuated the innate classicism of this music and, within that, its need to dance. What really excites this performance of the Polish is an approach to rhythm and articulation which keeps the textures open (the BIS sound engineers of course play their part in this) and the phrasing fluid.

Järvi’s reading of the symphony may sometimes lack temperament and that last degree of swagger but at tempi that would indeed keep Tchaikovsky’s imaginary dancers on their toes it exhibits great vitality and, more importantly, an abiding warmth and affection for what one can safely say is Tchaikovsky’s most lyric symphonic creation. The middle movements especially repay Järvi’s lightness of touch, spontaneous and luminous.

We remain ‘on stage’ for the rest of the disc – a selection of sweetmeats from Tchaikovsky’s theatre music, familiar or not, incidental or otherwise. The most interesting morsels come from the ‘dramatic chronicle’ Dmitri the Pretender and Vassily Shuisky: a darkly contemplative and fleetingly tormented Introduction and a rather graceful Mazurka.

But the most touching item has to be the tiny Serenade that Tchaikovsky wrote for the name day of his friend and champion Nikolai Rubinstein, the man who first conducted the Third Symphony. It’s amazing what can be revealed in three minutes and in this very personal charmer we graduate from wistful introspection to hymnic admiration in less time than it takes to realise that Tchaikovsky has fleetingly and so very discreetly opened his heart to his friend.

Symphony No 4

Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra / Mariss Jansons (Chandos)

A high emotional charge runs through Jansons’s performance of the Fourth, yet this rarely seems to be an end in itself. There’s always a balancing concern for the superb craftsmanship of Tchaikovsky’s writing: the shapeliness of the phrasing; the superb orchestration, scintillating and subtle by turns; and most of all Tchaikovsky’s marvellous sense of dramatic pace. Rarely has the first movement possessed such a strong sense of tragic inevitability, or the return of the ‘fate’ theme in the finale sounded so logical. The playing of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra is first-rate: there are some gorgeous woodwind solos and the brass achieve a truly Tchaikovskian intensity. Recordings are excellent.

Symphonies Nos 4-6

Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra / Evgeny Mravinsky (DG) Recorded 1960

These recordings are landmarks not just of Tchaikovsky interpretation but of recorded orchestral performances in general. The Leningrad Philharmonic play like a wild stallion only just held in check by the willpower of its master. Every smallest movement is placed with fierce pride; at any moment it may break into such a frenzied gallop that you hardly know whether to feel exhilarated or terrified. The whipping up of excitement towards the fateful outbursts in Symphony No 4 is astonishing – not just for the discipline of the stringendos themselves, but for the pull of psychological forces within them. Symphony No 5 is also mercilessly driven, and pre-echoes of Shostakovian hysteria are particularly strong in the coda’s knife-edge of triumph and despair. No less powerfully evoked is the stricken tragedy of the Pathétique. Rarely, if ever, can the prodigious rhythmical inventiveness of these scores have been so brilliantly demonstrated.

The fanatical discipline isn’t something one would want to see casually emulated but it’s applied in a way which sees far into the soul of the music and never violates its spirit. Strictly speaking there’s no real comparison with Mariss Jansons’s Chandos issues, despite the fact that Jansons had for long been Mravinsky’s assistant in Leningrad. His approach is warmer, less detailed, more classical, and in its way very satisfying. Not surprisingly, there are deeper perspectives in the Chandos recordings, but DG’s refurbishing has been most successful, enhancing the immediacy of sound so appropriate to the lacerating intensity of the interpretations.

Symphony No 5

Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra / Mariss Jansons (Chandos)

With speeds which are fast but never breathless and with the most vivid recording imaginable, this is as exciting an account as we have had of this symphony. In no way does this performance suggest anything but a metropolitan orchestra, and Jansons keeps reminding one of his background in Leningrad in the great years of Mravinsky and the Philharmonic. Nowhere does the link with Mravinsky emerge more clearly than in the finale, where he adopts a tempo very nearly as hectic as Mravinsky’s on his classic DG recording. In the first movement he resists any temptation to linger, prefering to press the music on, and the result sounds totally idiomatic. In the slow movement Jansons again prefers a steady tempo but treats the second theme with delicate rubato and builds the climaxes steadily, not rushing his fences, building the final one even bigger than the first. In the finale it’s striking that he follows Tchaikovsky’s notated slowings rather than allowing extra rallentandos – the bravura of the performance finds its natural culmination.

The Oslo string ensemble is fresh, bright and superbly disciplined, while the wind soloists are generally excellent. The Chandos sound is very specific and well focused despite a warm reverberation, real-sounding and three-dimensional with more clarity in tuttis than the rivals.

Symphony No 6. The Seasons

Russian National Orchestra / Mikhail Pletnev pf (Virgin Classics / Erato)

There’s no denying that Russian orchestras bring a special intensity to Tchaikovsky, and to this symphony in particular. But, in the past, we have had to contend with lethal, vibrato-laden brass and variable Soviet engineering. Not any more. Pianist Mikhail Pletnev formed this orchestra in 1990 from the front ranks of the major Soviet orchestras, and the result here is now regarded as a classic. The brass still retain their penetrating power, and an extraordinary richness and solemnity before the symphony’s coda; the woodwind make a very melancholy choir; and the strings possess not only the agility to cope with Pletnev’s aptly death-defying speed for the third movement march, but beauty of tone for Tchaikovsky’s yearning cantabiles. Pletnev exerts the same control over his players as he does over his fingers, to superb effect. The dynamic range is huge and comfortably reproduced with clarity, natural perspectives, a sense of instruments playing in a believable acoustic space, and a necessarily higher volume setting than usual. Marche slave’s final blaze of triumph, in the circumstances, seems apt.

Pletnev finds colours and depths in The Seasons that few others have found even intermittently. Schumann is revealed as a major influence, not only on the outward features of the style but on the whole expressive mood and manner. And as a display of pianism the whole set is outstanding, all the more so because his brilliance isn’t purely egotistic. Even when he does something unmarked – like attaching the hunting fanfares of ‘September’ to the final unison of ‘August’ – he’s so persuasive that you could believe that this is somehow inherent in the material. This is all exceptional playing, and the recording is ideally attuned to all its moods and colours.

Symphony No 6, 'Pathétique'

MusicAeterna / Teodor Currentzis (Sony Classical)

The finale opens with an exhalation from Currentzis, translated by the strings into a memorial of overlapping sighs and then punctuated by what sounds like the bass drum from the march. At this point the Berlin studio acoustic expands to cavernous dimensions to contain and then bury the symphony’s last rites. There is more playing on the lip of the volcano from col legnostrings and snarling, muted horns, more outstanding bassoon solos coloured on a palette from muddy brown to that black again.

It’s early days, but only the most exalted of comparisons suggest themselves: to Bernstein (DG, 5/87), Cantelli (EMI, 6/53), Karajan (take your pick) or Mravinsky (DG, considered afresh in November 2015): all hewn out of different performing traditions while sculpted in relief from them, though none save Mravinsky executed to the present, uncanny degree of controlled ferocity. There is a closer, more pertinent relation with Mikhail Pletnev’s first essay (Virgin Classics, 1/92): a hand picked band, moulded in the image of a young, mercurial musician mature beyond his years, working hand in glove with a studio team prepared to do things differently. I remember the storm unleashed by that recording 25 years ago. Will this also upset some applecarts? It is an unsettling experience.

Manfred Symphony. The Voyevoda, Op 78

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko (Naxos)

Petrenko’s Manfred emerges from the gothic greys of the opening wind chorale to vent his heartache in an emotive surge of string sound. And to ensure that we’ve grasped the measure of his despair, he repeats himself. Petrenko’s Byronic petulance makes something really stirring of the self-loathing – Tchaikovsky’s as much as that of Byron’s anti-hero. But the real miracle of this first movement is the vision of idealised love emerging so tenderly in what one might normally call the development. The palest clarinet against muted tremolando strings takes us directly to the heart of the matter, and Petrenko and his orchestra don’t disappoint. Likewise in the epic coda, where anguish is again writ large in overreaching horns and trumpets. No superfluous tam-tam, thankfully.

The dazzling apparitions of the second movement’s light-catching waterfall are sharply etched, and if Petrenko has a rather leisurely idea of what constitutes Andante con moto in the third movement, he can’t be blamed for loving this vintage Tchaikovsky melody too much. The playing, again, is lovely. Petrenko also keeps his head in the inferno of the finale, emphasising Tchaikovsky the classicist in the hard-working fugue. The ‘phantom’ organ, though impressively caught here, gets no better, but is quickly forgotten amid the serenity of the final pages.

The opening pages of The Voyevoda seem to suggest a psychological summit meeting between Manfred and Herman from The Queen of Spades. Its galloping obsessiveness ratchets up the torment again. The bass clarinet gives everyone the evil eye; no wonder Tchaikovsky tried to destroy it. This is impressive – and, at Naxos’s pricing, not to be missed.

Ballets

Swan Lake, Op 20

Montreal Symphony Orchestra / Charles Dutoit (Decca)

No one wrote more beautiful and danceable ballet music than Tchaikovsky, and this account of Swan Lake isa delight throughout. This isn’t only because of the quality of the music, which is here played including additions the composer made after the premiere, but also thanks to the richly idiomatic playing of Charles Dutoit and his Montreal orchestra in the superb and celebrated location of St Eustache’s Church in that city. Maybe some conductors have made the music even more earthily Russian, but the Russian ballet tradition in Tchaikovsky’s time was chiefly French and the most influential early production of this ballet, in 1895, was choreographed by the Frenchman Marius Petipa. Indeed, the symbiosis of French and Russian elements in this music (and story) is one of its great strengths, the refinement of the one being superbly allied to the vigour of the other, notably in such music as the Russian Dance, with its expressive violin solo.

This is a profoundly romantic reading of the score, and the great set pieces such as the Waltz in Act 1 and the marvellous scene of the swans on a moonlit lake that opens Act 2 are wonderfully evocative; yet they do not overshadow the other music, which supports them as gentler hills and valleys might surround and enhance magnificent, awe-inspiring peaks, the one being indispensable to the other. You do not have to be a ballet aficionado to fall under the spell of this wonderful music, which here receives a performance that blends passion with an aristocratic refinement and is glowingly recorded.

The Sleeping Beauty

London Symphony Orchestra / André Previn (EMI / Warner Classics)

Back in the 1950s there was quite a spate of complete-ballet recordings, but in recent years there have been very few, and this is the first of The Sleeping Beauty since Ansermet's slightly cut version of 1959. Earlier still in 1957 Dorati recorded every note with the Minneapolis orchestra but these discs have been out of the British record catalogue for some years, and the sound never quite did the music justice. Andre Previn's new version is much the best there has ever been-the best played and the best recorded. He uses the edition published in Moscow in 1952 (and soon to be available as an Eulenburg miniature score) and there are no cuts.

The Nutcracker

Kirov Opera Chorus and Orchestra / Valery Gergiev (Philips)

The Nutcracker as a short ride in a fast machine. Every now and then in Gramophone, you will read a recommendation from a reviewer that a particular recording needs a higher replay level than usual (emphatically not the case here), but, for what it’s worth, I found my most positive responses to this Nutcracker came after a higher than usual intake of caffeine. Obviously, a fair measure of Tchaikovsky’s score is meant to be continuous, but the Kirov’s animated action never lets up for a moment. It may have something to do with squeezing it on to a single disc (no pauses for breath, even between the First and Second Acts); and under the circumstances, it is not surprising that Gergiev doesn’t want to relax the momentum with the usual repeat of the leisurely ‘Grandfather Dance’. But this is probably how he conducts The Nutcracker at the Kirov (the recording was, in fact, made in Baden-Baden), and the elegance with which he moves from loud or fast sections of the score to quieter or slower ones – for example, the Arabian dance starting with a diminuendo – speak of ease gained from experience.

What we don’t have here is a Nutcracker to enhance the ambience of a room lit by Christmas tree lights and a log fire. My listening comparisons have included Svetlanov and Dutoit, both of whom have more time for old-world affection, warmth and evocation of atmosphere (and, like all other recordings, spread on to two discs). What we do have, however, is a realization that makes it clear why Stravinsky so loved the Tchaikovsky ballets. If there is an ostinato working away in the accompaniment, Gergiev gives it prominence and energy (the swift tempos help, of course). And credit for the very high yield of unusual features of this most inventively scored of all Tchaikovsky’s ballets should probably be evenly divided between Gergiev, the specific timbres of the orchestra and the very immediate sound.

When not caught up in the colourful exuberance of it all, one may stop to notice that the image lacks depth, the violins are a little thin in upper regions, and the brass occasionally play-out with the familiar Russian welly, wobble and weather (moderate amounts, heard after Svetlanov). Equally, the ear may be briefly diverted by minor imprecisions and the odd extraneous noise. But I wonder if there has ever been a Nutcracker so captured apparently ‘on the wing’, or, for that matter, so exciting.

1812 Overture

1812 Overture. Capriccio italien, Op 45 Beethoven Wellingtons Sieg, ‘Die Schlacht bei Vittoria’, Op 91

University of Minnesota Brass Band; Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra; London Symphony Orchestra / Antál Dorati (Mercury)

Both battle pieces incorporate cannon fire recorded at West Point, with Wellington’s Victory adding antiphonal muskets, the 1812 the University of Minnesota Brass Band and the bells of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller carillon. In a recorded commentary on the 1812 sessions, Deems Taylor explains how, prior to ‘battle’, roads were blocked and an ambulance crew put on standby. The actual weapons used were chosen both for their historical authenticity (period instruments of mass destruction) and their sonic impact, the latter proving formidable even today. In fact, the crackle and thunder of Wellington’s Victory could easily carry a DDD endorsement; perhaps we should, for the occasion, invent a legend of Daring, Deafening and potentially Deadly. Dorati’s conducting is brisk, incisive and dramatic. The 1812 in particular suggests a rare spontaneity, with a fiery account of the main ‘conflict’ and a tub-thumping peroration where bells, band, guns and orchestra conspire to produce one of the most riotous key-clashes in gramophone history.

Capriccio italien was recorded some three years earlier (1955, would you believe) and sounds virtually as impressive. Again, the approach is crisp and balletic, whereas the 1960 LSO Beethoven recording triumphs by dint of its energy and orchestral discipline. As ‘fun’ CDs go, this must be one of the best – provided you can divorce Mercury’s aural militia from the terrifying spectre of real conflict.

Francesca da Rimini. Romeo and Juliet. 1812 Overture. Eugene Onegin – Waltz; Polonaise

Santa Cecilia Academy Chorus and Orchestra, Rome / Antonio Pappano (EMI / Warner Classics)

With chorus added in the 1812 as well as the Waltz from Eugene Onegin, this is an exceptional Tchaikovsky collection, a fine start for Antonio Pappano’s recordings with his Italian orchestra. What is very striking is how refreshing the 1812 is when played with such incisiveness and care for detail, with textures clearly defined. It starts with the chorus singing the opening hymn, expanding thrillingly from an extreme pianissimo to a full-throated fortissimo.

A women’s chorus then comes in very effectively, twice over, for one of the folk-themes, and at the end the full chorus sings the Tsar’s Hymn amid the usual percussion and bells, though Pappano avoids extraneous effects, leaving everything in the hands of the orchestral instruments. It is equally refreshing to have the Waltz from Eugene Onegin in the full vocal version from the opera, again wonderfully pointed, as is the Polonaise which follows.

What comes out in all the items is the way that Pappano, in his control of flexible rubato, is just as persuasive here as he is in Puccini, demonstrating what links there are between these two supreme melodists. So he builds the big melodies into richly emotional climaxes without any hint of vulgarity, strikingly so in both Francesca da Rimini and Romeo and Juliet. Pappano is impressive in bringing out the fantasy element in Francesca, and in Romeo the high dynamic contrasts add to the impact of the performance. There have been many Tchaikovsky collections like this, but with well balanced sound, outstandingly rich and ripe in the brass section, this is among the finest.

Fantasy Overtures

Hamlet, Op 67. The Tempest, Op 18. Romeo and Juliet

Bamberg Symphony Orchestra / José Serebrier (BIS)

What a good idea to couple Tchaikovsky’s three fantasy overtures inspired by Shakespeare. José Serebrier writes an illuminating note on the genesis of each of the three, together with an analysis of their structure. He notes that once Tchaikovsky had established his concept of the fantasy overture in the first version of Romeo and Juliet in 1869 – slow introduction leading to alternating fast and slow sections, with slow coda – he used it again both in the 1812 Overture and Hamlet. The Tempest (1873) has similarly contrasting sections, but begins and ends with a gently evocative seascape, with shimmering arpeggios from strings divided in 13 parts.

It’s typical of Serebrier’s performance that he makes that effect sound so fresh and original. In many ways, early as it is, this is stylistically the most radical of the three overtures here, with sharp echoes of Berlioz in some of the woodwind effects. The clarity of Serebrier’s performance, both in texture and in structure, helps to bring that out, as does a warm and analytical BIS recording.

Hamlet, dating from much later, is treated to a similarly fresh and dramatic reading, with Serebrier bringing out the yearningly Russian flavour of the lovely oboe theme representing Ophelia. He may not quite match the thrusting power of his mentor, Stokowski, but he’s not far short, and brings out far more detail.

Serebrier is also meticulous in seeking to observe the dynamic markings in each score. Those in The Tempest are nothing if not extravagant – up to a fortissimo of five fs in the final statement of the love theme – yet Serebrier graduates the extremes with great care.

Hamlet, Op 67a – Overture and Incidental Music. Romeo and Juliet

Tatiana Monogarova sop Maxim Mikhailov bass Russian National Orchestra / Vladimir Jurowski (Pentatone)

At first glance this might look like the traditional pairing of Tchaikovsky’s two fantasy overtures – but you might have known that Vladimir Jurowski was likely to be more inquisitive than that. In 1891 a complete stage performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet took place in St Petersburg with music by Tchaikovsky. His fantasy overture, written for a charity event three years earlier, was heard again, this time filleted to roughly half its original length and reduced in scoring to the requirements of a theatre orchestra. The results are fascinating, not least for the ingenuity of Tchaikovsky’s cut-and-paste job, jump-cutting now with renewed urgency. Of course, one misses the symphonic weight of the original. The effect is more muted here, the scale diminished so as not to pre‑empt that moment in the actual drama. But Ophelia is more than ever at the heart of the piece, her plaintive oboe melody very much dominating this version and exquisitely played – as is everything – by the Russian National Orchestra, whose refinement has opened a new chapter in Russian orchestral playing. Ophelia’s first entrance, incidentally, is none other than the graceful ‘Alla tedesca’ second movement of Tchaikovsky’s Third Symphony, the Polish. How’s that for recycling? And there’s more with the Prelude to Act 4 scene 1, a poignant string elegy turned on wistful arabesques. That is one of the more substantial of the 16 clips and touchingly foreshadows Ophelia’s tragedy. She – the lovely Tatiana Monogarova – has a two-part mad scene or ‘melodrama’, where the spoken lines lend a stark reality to her delusions.

Those who know the original 1869 version of the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture will be aware that it’s another example of how much more interesting, though not necessarily better, a composer’s first thoughts can be. Fascinating is the earlier premonition of the great love theme and the way Tchaikovsky quite literally tosses it about in the more radical and certainly more violent development of the fight music: all gone in the revision!

Jurowski savours the differences and makes capital of the anomalies. Very exciting.

Variations on a Rococo Theme. Nocturne, Op 19 No 4. Pezzo capriccioso, Op 62. When Jesus Christ was but a child, Op 54 No 5. Was I not a little blade of grass?, Op 47 No 7. Andante cantabile, Op 11

Raphael Wallfisch vc English Chamber Orchestra / Geoffrey Simon (Chandos)

This account of the Rococo Variations is the one to have: it presents Tchaikovsky’s variations as he wrote them, in the order he devised, and including the allegretto moderato con anima that the work’s first interpreter, ‘loathsome Fitzenhagen’, so high-handedly jettisoned. (See also the review under Dvořák where Rostropovich uses the published score rather than the original version.) The first advantage is as great as the second: how necessary the brief cadenza and the andante that it introduces now seem, as an up-beat to the central sequence of quick variations (Fitzenhagen moved both cadenza and andante to the end). And the other, shorter cadenza now makes a satisfying transition from that sequence to the balancing andante sostenuto, from which the long-suppressed eighth variation is an obvious build-up to the coda – why, the piece has a form, after all! Raphael Wallfisch’s fine performance keeps the qualifying adjective ‘rococo’ in mind – it isn’t indulgently over-romantic – but it has warmth and beauty of tone in abundance. The shorter pieces are well worth having: the baritone voice of the cello suits the Andante cantabile and the Tatyana-like melody of the Nocturne surprisingly aptly. The sound is first-class.

Variations on a Rococo Theme

Mstislav Rostropovich vc Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

In the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Rostropovich uses the published score rather than the original version. However, he plays with such masterly Russian fervour and elegance that any criticism is disarmed. The music itself continually demonstrates Tchaikovsky's astonishing lyrical fecundity, as one tune leads to another, all growing organically from the charming 'rococo' theme. The recording is marvellously refined.

The description 'legendary' isn't a whit too strong for a disc of this calibre.

Souvenir de Florence

Sarah Chang, Bernhard Hartog vns Wolfram Christ, Tanjia Christ vas Georg Faust, Olaf Maninger vcs (EMI / Warner Classics)

Two of the finest string sextets ever written by Slavonic composers make an excellent coupling, particularly with such a starry line-up of musicians. Sarah Chang’s warmly individual artistry is superbly matched by players drawn from the Berlin Philharmonic, past and present. These are players who not only respond to each other’s artistry, but do so with the most polished ensemble and a rare clarity of inner texture, not easy with a sextet.

Souvenir de Florence is given the most exuberantly joyful performance. Written just after he had left Florence, having completed the Queen of Spades, Tchaikovsky was prompted to compose one of his happiest works, one which for once gave him enormous pleasure. The opening movement’s bouncy rhythms in compound time set the pattern, with the second subject hauntingly seductive in its winning relaxation.

The Adagio cantabile second movement is tenderly beautiful, with the central section sharply contrasted, while the folk-dance rhythms of the last two movements are sprung with sparkling lightness. There are now dozens of versions of this winning work in the catalogue, both for sextet and string orchestra, but none is more delectable than this.

Equally, the subtlety as well as the energy of Dvořák’s Sextet is consistently brought out by Chang and her partners, with the players using a huge dynamic range down to the gentlest pianissimo. Here, too, it just outshines the competition.

Chamber works

String Quartets Nos 1-3. String Quartet Movement (1865). Souvenir de Florence

Klenke Quartet with Harald Schoneweg va Klaus Kämper vc (Berlin Classics)

For some years, the touchstone for the Tchaikovsky quartets has been the 1993 Borodin Quartet recordings (Teldec), eloquent accounts that reach deeply into the music. The Klenke Quartet immediately invite comparison, with an identical programme and, with one or two exceptions, timings for the individual movements within a few seconds of each other. Annegret Klenke and her colleagues have achieved a remarkable unity of tone and style, giving their interpretations a powerful identity, with sharply defined contrasts between the different episodes and movements.

In the harrowing funeral march that forms the slow movement of Op 30, the Klenkes arrest one’s attention immediately; the opening chordal motif is relentlessly sustained with little or no vibrato; against this the impassioned, vibrant violin phrases stand out dramatically. For the movement’s consolatory middle section, the quartet find a remarkable sweet, silky sound and the icy final chords encapsulate perfectly the movement’s bleak emotional landscape.

Tchaikovsky’s string-writing often exploits the strong virtuoso tradition that already existed in mid-19th-century Russia and the brilliant passages in the finales of the first two quartets are given here in a particularly exciting, bold manner. However, the middle movements of the Second Quartet are less satisfying than the rest of the programme – the Scherzo in places sounding rather sleepy, its Trio surprisingly bland, and in the Adagio some of the playing seems too heavily emphatic. But such small disappointments are amply compensated by an enchanting account of the Sextet; the soaring melodies of the first two movements played with radiant tone, and the Scherzo and finale given with exceptional energy and verve.

Piano Trio

Vienna Piano Trio (Dabringhaus und Grimm)

This version of the Tchaikovsky measures up extremely well against its competition; moreover it is (like all chamber recordings from this source) very well balanced. Pianist Stefan Mendl is able to dominate yet become a full member of the partnership throughout. The second movement’s variations open gently but soon develop the widest range of style, moving through Tchaikovsky’s kaleidoscopic mood-changes like quicksilver and often with elegiac lyrical feeling.

But what makes this disc especially recommendable is the inclusion of Smetana’s G minor Piano Trio, which the composer himself premiered in 1855. All three movements are in the home key and thematically linked yet are enticingly diverse, the first with strong contrasts of dynamic and tempo, the second a most engaging scherzo (marked non agitato and with slower interludes), while the rondo finale bursts with energy (especially as presented here). All in all a real winner of a disc that can be highly recommended on all counts.

Piano Works

18 Morceaux, Op 72

Mikhail Pletnev pf (DG) Recorded live 2004

Mikhail Pletnev’s persuasive 1986 re-cording of Tchaikovsky’s 18 Morceaux for Melodiya was hampered by strident sound and an ill-tuned piano. Happily, a state-of-the-art situation prevails in this new live recording, extending, of course, to Pletnev’s own contributions. His caring, characterful and technically transcendent way with this cycle casts each piece in a three-dimensional perspective that honours the composer’s letter and spirit beyond the music’s ‘salon’ reputation, while making the most of its pianistic potential. The results are revelatory, akin to, say, Ignaz Friedman’s illuminating re-creations of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words.

The Fifth Morceau, ‘Méditation’, demonstrates the Pletnev-Tchaikovsky chemistry at its most sublime. The melodies are firmly projected yet flexibly arched over the bar-lines, as if emerging from different instruments, culminating in a febrile central climax that gently dissipates into some of the most ravishing trills on record. In No 8, ‘Dialogue’, Pletnev elevates Tchaikovsky’s quasi parlando with the type of offhand skill and pinpoint timing of a master actor who knows just which lines to throw away.

Note, too, the deliciously pointed scales and music-box colorations in No 13, ‘Echo rustique’. Shades of Liszt’s Third Liebestraum seep into No 14, ‘Chant élégiaque’, in what amounts to a masterclass in how to sustain long melodies against sweeping accompaniments. A stricter basic pulse throughout No 9, ‘Un poco di Schumann’, might have made the dotted rhythms and two strategically placed ritenutos more obviously Schumannesque, yet there’s no denying the inner logic the looser treatment communicates.

There’s extraordinary virtuosity behind the musical insights. For example, the interlocking octaves in the coda to No 7, ‘Polacca de concert’, are unleashed with Horowitz-like ferocity and not a trace of banging. The rapid, vertigo-inducing triplet runs in No 10, ‘Scherzo-fantaisie’, could scarcely be more even and controlled. Pletnev is all over the final, unbuttoned trepak in grand style, and he certainly makes the glissandos swing. A fresh, unfettered account of Chopin’s C sharp minor Nocturne is offered as an encore to this urgently recommended recital.

Solo Piano Works

Peter Donohoe pf (Signum Classics)

Russian and Soviet music and culture run like a river through Peter Donohoe’s distinguished career. His joint silver medal at the 1982 Tchaikovsky Competition cemented a relationship with the country, its musicians and its public that is ongoing.

My instant reaction on pushing ‘play’ and hearing the first bars was ‘Ah – this is going to be good’. And so it proves, perhaps the most consistently enjoyable and satisfying recording of Tchaikovsky piano solos of recent years. There’s a lightness of touch, a crisp transparency and clarity of texture that sends the opening ‘Scherzo à la russe’ spinning off into the realms of sheer delight, leaving you to wonder, as does Donohoe in a brief booklet aside, why Tchaikovsky’s piano music should remain so infrequently performed in concert programmes, ‘containing as it does all of the composer’s characteristic harmony [and] wonderful melodic gift’.

Vocal works

Liturgy of St John Chrysostom. Nine Sacred Choruses. An Angel Crying

Corydon Singers / Matthew Best (Hyperion)

Tchaikovsky’s liturgical settings have never quite caught the popular imagination which has followed Rachmaninov’s (his All-Night Vigil, at any rate). They are generally more inward, less concerned with the drama that marks Orthodox celebration than with the reflective centre which is another aspect. Rachmaninov can invite worship with a blaze of delight, setting ‘Pridite’; Tchaikovsky approaches the mystery more quietly. Yet there’s a range of emotion which emerges vividly in this admirable record of the Liturgy together with a group of the minor liturgical settings which he made at various times in his life. His ear for timbre never fails him. It’s at its most appealing, perhaps, in the lovely ‘Da ispravitsya’ for female trio and answering choir, beautifully sung here; he can also respond to the Orthodox tradition of rapid vocalisation, as in the Liturgy’s Creed and in the final ‘Blagosloven grady’ (in the West, the Benedictus). Anyone who still supposes that irregular, rapidly shifting rhythms were invented by Stravinsky should give an ear to his Russian sources, in folk poetry and music but also in the music of the Church.

Matthew Best’s Corydon Singers are old hands at Orthodox music and present these beautiful settings with a keen ear for their texture and ‘orchestration’. The recording was made in an (unnamed) ecclesiastical acoustic of suitable resonance, and sounds well.

‘Romances’

Christianne Stotijn mez Julius Drake pf (Onyx Classics)

For the most part these are angst-ridden stories of death and lost love. The two best-known songs open proceedings: ‘At the Ball’, with its reminiscence of unrequited passion to the lilt of a sad waltz, and then ‘None but the lonely heart’. Everyone conceivable from Rosa Ponselle to Frank Sinatra has recorded this, but Stotijn loses nothing in comparison with ghosts from the past. Her voice is a full-blooded mezzo but steady and true, without a hint of that vibrato that can often disturb the line in Slavonic singers (Stotijn is from the Netherlands).

The emotional climax of the selection comes with ‘The Bride’s Lament’. This outpouring of grief can seem over melodramatic but Stotijn and Drake find exactly the right mood. The piano parts are superbly done: in every sense these songs are duets. There are a couple of other light moments – ‘Cuckoo’, one of 16 children’s songs composed in the 1880s, and a ‘Gypsy Song’ from around the same time. Tchaikovsky’s songs are not nearly well enough known and this superb recital should encourage more interest in them.

The Snow Maiden

Irina Mishura-Lekhtman mez Vladimir Grishko ten Michigan University Musical Society Choral Union; Detroit Symphony Orchestra / Neeme Järvi (Chandos)

Tchaikovsky wrote his incidental music for Ostrovsky’s Snow Maiden in 1873, and though he accepted it was not his best, he retained an affection for it and was upset when Rimsky-Korsakov came along with his full-length opera on the subject. The tale of love frustrated had its appeal for Tchaikovsky, even though he was not to make as much as Rimsky did of the failed marriage between Man and Nature. But though he did not normally interest himself much in descriptions of the natural world, there are charming pieces that any lover of Tchaikovsky’s music will surely be delighted to encounter. A strong sense of a Russian folk celebration, and of the interaction of the natural and supernatural worlds, also comes through, especially in the earlier part of the work. There’s a delightful dance and chorus for the birds, and a powerful monologue for Winter; Vladimir Grishko, placed further back, sounds magical.

Natalia Erassova (for Chistiakov’s recording on CdM) gets round the rapid enunciation of Lel’s second song without much difficulty, but doesn’t quite bring the character to life; Mishura-Lekhtman has a brighter sparkle. Chistiakov’s Shrove Tuesday procession goes at a much steadier pace than Järvi’s, and is thus the more celebratory and ritual where the other is a straightforward piece of merriment. Both performances have much to recommend them, and it isn’t by a great deal that Järvi’s is preferable.

Eugene Onegin, Op 24

Dmitri Hvorostovsky bar Eugene Onegin Nuccia Focile sop Tatyana Neil Shicoff ten Lensky Sarah Walker mez Larina Irina Arkhipova mez Filipyevna Olga Borodina contr Olga Francis Egerton ten Triquet Alexander Anisimov bass Prince Gremin Hervé Hennequin bass Captain Sergei Zadvorny bass Zaretsky Orchestre de Paris; St Petersburg Chamber Choir / Semyon Bychkov (Philips)

This is a magnificent achievement on all sides. In a recording that is wide in range, the work comes to arresting life under Bychkov’s vital direction. Too often of late, on disc and in the theatre, the score has been treated self-indulgently and on too large a scale. Bychkov makes neither mistake, emphasising the unity of its various scenes, never lingering at slower tempi than Tchaikovsky predicates, yet never moving too fast for his singers.

Focile and Hvorostovsky prove almost ideal interpreters of the central roles. Focile offers keen-edged yet warm tone and total immersion in Tatyana’s character. Aware throughout of the part’s dynamic demands, she phrases with complete confidence, eagerly catching the girl’s dreamy vulnerability and heightened imagination in the Letter scene, which has that sense of awakened love so essential to it. Then she exhibits Tatyana’s new-found dignity on Gremin’s arm and finally her desperation when Onegin reappears to rekindle her romantic feelings.

Hvorostovsky is here wholly in his element. His singing has at once the warmth, elegance and refinement Tchaikovsky demands from his anti-hero. He suggests all Onegin’s initial disdain, phrasing his address to the distraught and humiliated Tatyana – Focile so touching here – with distinction, and brings to it just the correct

bon ton, a kind of detached humanity. He fires to anger with a touch of the heroic in his tone when challenged by Lensky, becomes transformed and single-minded when he catches sight of the ‘new’ Tatyana at the St Petersburg Ball. Together he, Focile and Bychkov make the finale the tragic climax it should be: indeed, this passage is almost unbearably moving in this reading.

Shicoff has refined and expanded his Lensky since he recorded it for Levine (DG). His somewhat lachrymose delivery suits the character of the lovelorn poet, and he gives his big aria a sensitive, Russian profile, full of much subtlety of accent, the voice sounding in excellent shape, but there is a shade too much self-regard when he opens the ensemble at Larin’s party with ‘Yes, in your house’. Anisimov is a model Gremin, singing his aria with generous tone and phrasing while not making a meal of it. Olga Borodina is a perfect Olga, spirited, a touch sensual, wholly idiomatic with the text – as, of course, is the revered veteran Russian mezzo Arkhipova as Filipyevna, an inspired piece of casting. Sarah Walker, Covent Garden’s Filipyevna, is here a sympathetic Larina. Also from the Royal Opera comes Egerton’s lovable Triquet; but whereas Gergiev, in the theatre, dragged out his couplets inordinately, Bychkov once more strikes precisely the right tempo.

There will always be a very special place in the discography of the opera for the vintage Russian versions but, as a recording, they are naturally outclassed by the Philips, which now becomes the outright recommendation.

Iolanta

Andrei Bondarenko, Dmytro Popov, Justyna Samborska, Olesya Golovneva, Dalia Schaechter, Marta Wryk, Marc-Olivier Oetterli, John Heuzenroeder, Alexander Vinogradov, Vladislav Sulimsky Gürzenich-Orchester Köln, Chor der Oper Köln / Dmitri Kitaenko (Oehms Classics)

Leading the cast is the excellent young Russian Olesya Golovneva as Iolanta. Her roles explore the lighter end of the scale – Queen of the Night, Gilda, Zerbinetta – but she also covers lyric repertoire such as Tatyana. As anticipated from this CV, she floats high notes beautifully and her arioso ‘Otchego eto prezhde ne znala’ (Why, until now, have I not shed tears?) is full of tender fragility. As a young innocent, Golovneva’s Iolanta is preferable to the fuller, darker soprano of Netrebko, who arguably took it into her repertory a fraction too late.

Alexander Vinogradov’s soft-grained bass is rock-solid and on magnificent form as Iolanta’s father, the protective King René, proving far stronger than the woolly Vitalij Kowaljow for DG. Vladislav Sulimsky, as the Moorish physician Ibn-Hakia, possesses a powerful baritone, making the most of his aria, with its oriental inflections.

Intruding into the secret garden come Robert, Duke of Burgundy, betrothed to Iolanta (although in love with another), and his friend Vaudémont. In a coup of luxury casting, considering the role’s brevity, Andrei Bondarenko makes for a resplendent Robert, easily the equal of Dmitri Hvorostovsky on Valery Gergiev’s Philips recording.

Tenor Dmytro Popov is in mellifluous, heady voice as Vaudémont. Discovering Iolanta asleep in the garden, Vaudémont falls in love with her and discovers her blindness through her inability to distinguish between white and red roses. Ther duet is the crux of the opera and Popov and Golovneva are incredibly touching, with Kitaenko unleashing a tremendous orchestral outpouring at the end. Most of the smaller roles are well taken, apart from the clotted mezzo singing Martha, with a vibrant contribution from the chorus of Cologne Opera in the closing hymn of praise after Ibn-Hakia works his miracle and cures Iolanta. A top-drawer recording of an increasingly significant opera.

The Queen of Spades

Misha Didyk, Tatiana Serjan, Larissa Diadkova, Alexey Shishlyaev, Alexey Markov, Kinderchor der Bayerischen Staatsoper & Chor and Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks / Mariss Jansons (BR Klassik)

While Eugene Onegin is Tchaikovsky’s most popular opera, there’s a fair argument that The Queen of Spades is his best. A gripping drama, it requires performances where you believe in Herman’s psychological descent as the desire to learn the secret of the three cards from the old Countess consumes everything, including his love for Lisa.

The opera has been lucky on disc, dominated in recent decades by recordings from Valery Gergiev and Seiji Ozawa, both from the early 1990s. They are joined by this resplendent account from Mariss Jansons and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, recorded in concert. Jansons has a fine pedigree in Tchaikovsky (his cycle of the symphonies for Chandos still holds strong) and he paces the opera unerringly well, building tension superbly. His Bavarians respond with atmospheric playing, burnished strings and dark woodwind coloration to the fore.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario